tl;dr: A visit to Sukiyabashi Jiro in Tokyo offers a vivid Lean lesson: extraordinary quality and efficiency, but at a pace that raises questions about flow, pull, and the customer experience.

Before Katie Anderson's Japan Study Trip in November, I spent six days in Kyoto and Tokyo with two friends (one of whom is cropped out of the photo below for privacy, and the other is represented by an emoji that approximates his general expression, LOL).

Through our hotel concierge, we were able to snag lunchtime seats at the famed Sukiyabashi Jiro restaurant, which was made famous by the film “Jiro Dreams of Sushi” (as I blogged about years ago).

You're not allowed to take photos in the restaurant, but they'll take a photo afterward outside. I'm in the photo, of course, and to the far left is Yoshikazu Ono, the son of the film's main subject and the founder of the restaurant, Jiro Ono.

Jiro was once a 3-star Michelin selection, the first-ever sushi restaurant to receive that honor. But they lost the stars in 2019 because they're technically no longer open to the public. You can only book through hotel concierges (and probably other insider connections).

Jiro Ono is now 99 years old, and it's said you can't guarantee you'll see him, but he will make appearances at the restaurant. But his son, Yoshikazu, carries on with the traditions and excellence. Ono's other son, Takashi, started his own restaurant in Tokyo.

I write this post not to brag but to share some observable details about their operations. The price of the meal was actually on par with a high-end omakase sushi meal in Dallas or other cities. But the price is a bit lower because no alcohol is served (Jiro believes green tea is what complements the sushi best).

So I'm not saying it was “affordable,” but it wasn't the most expensive meal I've had.

Hear Mark read this post — subscribe to Lean Blog Audio

The Sukiyabashi Jiro Experience: Legacy, Access, and Expectations

We arrived early and were greeted promptly when the restaurant opened. There are just ten seats, and I was surprised that five were empty for the meal. It was just the three of us and two other diners.

The one thing that surprised me most was the pacing of the meal.

Sushi at Speed: Cycle Time, Flow, and a Push System

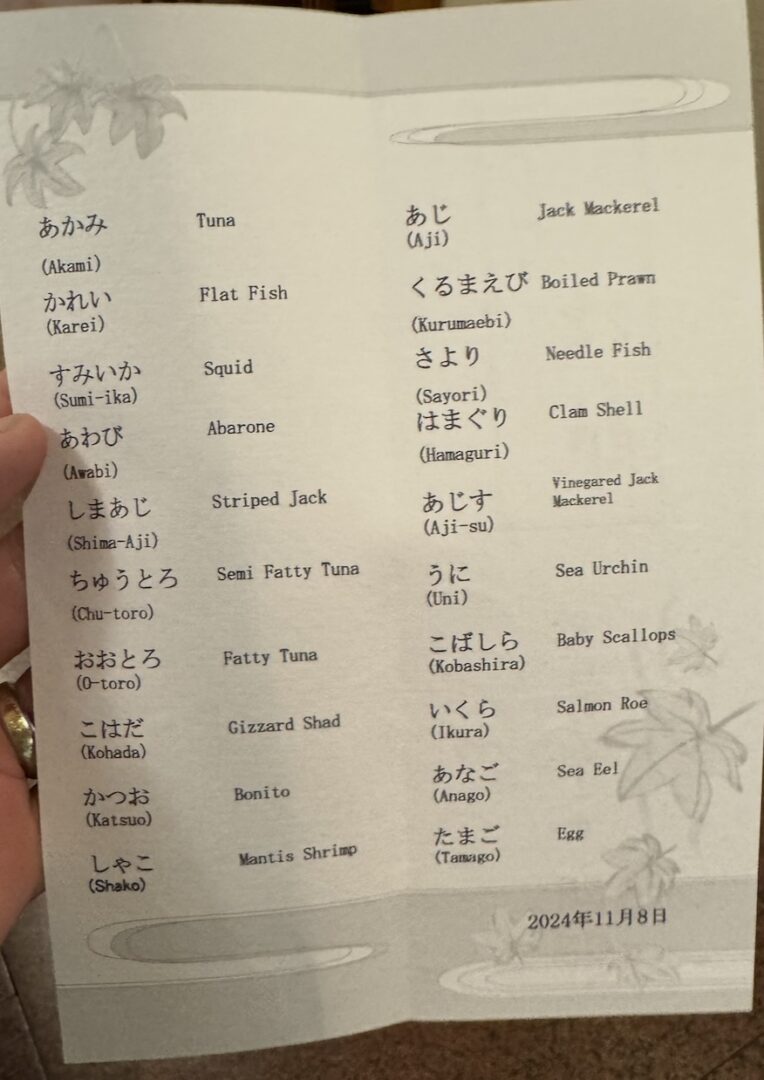

The menu is omakase (chef's choice), and they offer 20 pieces of nigiri sushi (fish on sushi rice, with some other flavors added, like yuzu citrus).

Here was the day's menu, which is said to be based on what's fresh and good at the fish market that morning:

Behind the Counter: A Highly Engineered Sushi Production System

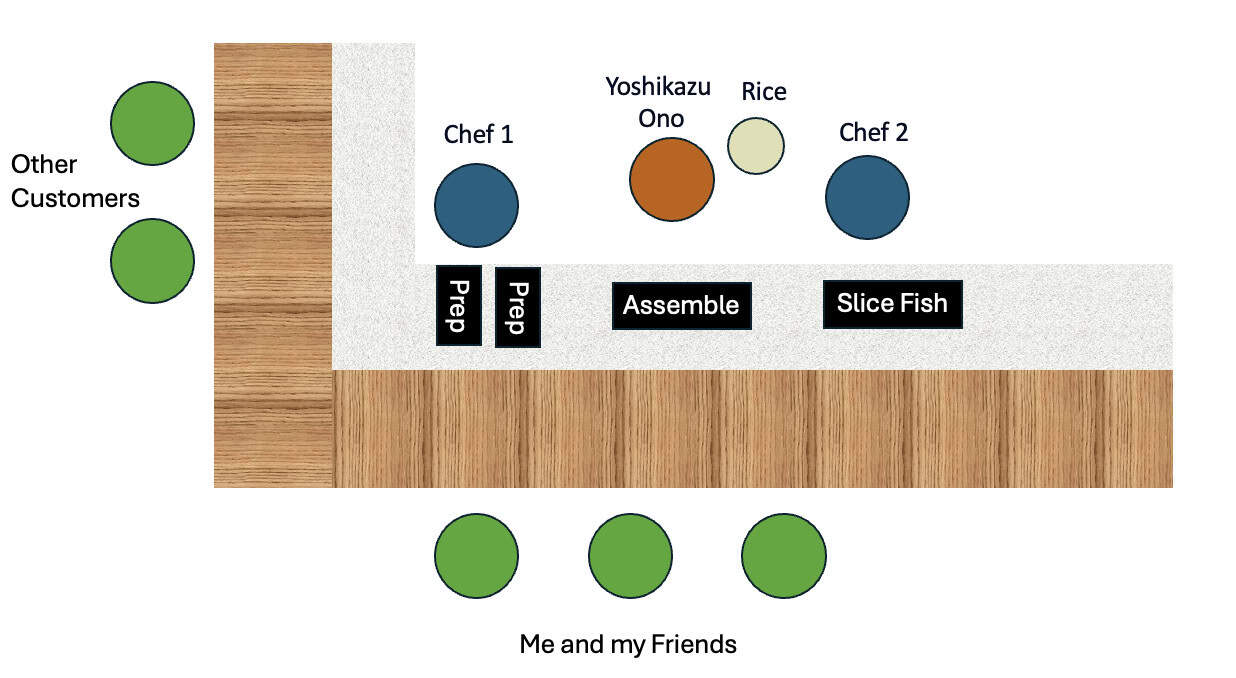

Rice is prepared in advance (that morning, I'm sure), cooked in a batch, and stored in a round bamboo container to Yoshikazu's left.

There were two (sometimes three) assistant prep chefs working around him. One was generally slicing fish and seafood in the precise sushi manner, cutting a batch of five pieces for the five customers. The slices were put on a tray that was generally moved to Yoshikazu's right, and a course or two was typically queued up for him to do the assembly work.

Here's my rough diagram:

I'm not here to critique the layout or their flow. It seems to work for them. It's a fine-tuned sushi-making machine.

And I guess that's my only criticism. The pacing of the courses was FAST.

I didn't have a stopwatch out, but it took about 20 minutes to serve the 20 courses. It was definitely a push system, with Yoshikazu handing you the next piece… So you'd better be ready.

Push vs. Pull: When the Chef Sets the Pace

I didn't exactly feel rushed… but it was a little quicker than I would have preferred. Everything seemed driven by Yoshikazu's (and team's) “cycle time” (how long it took to produce pieces) rather than by the customer's “takt time” (the rate at which we wanted sushi).

It might have taken Yoshikazu 12 seconds to assemble each piece, as he handed them to customers one by one (no batching). It was make-serve-make-serve-make-serve, etc., rotating around the five of us. It was almost like he was dealing blackjack cards around a table in Vegas.

The meal might have been served more slowly had all ten seats been filled.

The flow of components going to Yoshikazu's ensured he had no “waste of waiting.” It seemed optimized around the chef's efficiency, not the customer's needs.

Optimized for the Chef, Not the Customer?

Don't get me wrong. Everything was delicious. The menu had some of my favorites (like uni) and some fish or seafood that was new to me.

But it was quick.

Customer Experience at High Speed

President Barack Obama dined there in 2014, served by Jiro-san; it was said to be a 20-minute sushi meal.

Now, when the sushi is over, things become a bit more leisurely. My friends and I were moved to a booth-style table, where we were served the most amazing cantaloupe-style melon I've ever had. It was so fresh and naturally sweet — and I don't normally like cantaloupe. We were allowed to linger over that and eat at our own pace.

Different Dimensions of Quality: Product vs. Experience

So the whole process makes me think of the dimensions of quality. There are multiple dimensions of quality in a hospital (such as the quality of care and the quality of the experience).

When I worked for Dell Computer, the quality of the computer products mattered, but Dell was also selling the quality of the corporate buying and delivery process (not just avoiding being late, but also not arriving early when a company's loading dock and IT team might not be there and ready).

The restaurant lived up to the food quality component by far. But “service quality” is very subjective. Was the meal too fast? Would it have been better if the chef had interacted with us at all? I don't know how good his English is, but he didn't interact with the two Japanese customers to my left, either.

Should the chef be on a bit of a customer “pull” system where he adjusts his pacing to the diners' pace, slowing down as necessary?

What Sushi Teaches Us About Healthcare, Manufacturing, and Service

When I took a sushi-making class with a chef in Japan years ago, pre-COVID, he told us that each piece of sushi should be bite-sized. And that means customers with smaller mouths (he said “women”) would get smaller pieces than those with bigger mouths. In the U.S., you might get sued for not giving the same amount of sushi to each customer who is paying the same price.

My visit to Sukiyabashi Jiro was a fascinating experience–not just for the exceptional sushi but also for the insights into craftsmanship, efficiency, and customer experience. The precision and speed of service were remarkable, though it raised questions about the balance between efficiency and hospitality. It reminded me that quality isn't just about the end product–it's also about the experience of receiving it.

Read more about my sushi-making class here.

Reflection Questions: Efficiency, Flow, and Customer Experience

Questions for you…

- Would you prefer a sushi experience that's hyper-efficient or one that allows more time for conversation and savoring each piece?

- How do you define great service–by the speed and precision of delivery or by the level of engagement with the chef?

- Have you ever had an experience where efficiency came at the cost of comfort or enjoyment? How did that impact your perception of quality?

- If Jiro's sushi-making process were a Lean system, would you see the speed as waste reduction or as an area for customer-driven improvement?

- What lessons from this experience could be applied in other industries–like healthcare, manufacturing, or hospitality?

Conclusion: Quality Is More Than Speed

My experience at Sukiyabashi Jiro reinforced a lesson that shows up again and again in Lean work across industries: extraordinary quality is multi-dimensional. It's not just about technical excellence or efficiency–it's also about flow, pull, and how the customer experiences the work as it's delivered.

Jiro's sushi represents craftsmanship at the highest level, supported by disciplined routines, standardized work, and relentless improvement. At the same time, the pace of the experience raises important questions that Lean leaders should wrestle with honestly:

Who is the system optimized for? Whose time matters most? And how do we balance efficiency with human experience?

These same questions apply far beyond sushi. In healthcare, manufacturing, and service organizations, improvement efforts can unintentionally drift toward optimizing internal cycle time while losing sight of customer takt time. Lean thinking challenges us to do better–to design systems that deliver both exceptional outcomes and meaningful experiences.

If there's one takeaway from Sukiyabashi Jiro, it's this: true quality isn't defined solely by speed or perfection of output, but by how well the system serves the people it exists for. That tension–between efficiency and experience–is where the most valuable improvement conversations begin.

Other Posts About Sushi

If you’re working to build a culture where people feel safe to speak up, solve problems, and improve every day, I’d be glad to help. Let’s talk about how to strengthen Psychological Safety and Continuous Improvement in your organization.

In healthcare, hospitals focus on reducing patient wait times, but rushing through appointments can impact the quality of care and patient satisfaction. Finding the right balance between efficiency and personalized attention is key.

In manufacturing, companies optimize production cycles, but over-prioritizing speed can lead to errors or quality concerns. A lean but flexible approach ensures efficiency without sacrificing product quality.

In hospitality, restaurants and hotels should consider both workflow efficiency and guest enjoyment—ensuring timely service while allowing customers to feel valued and not rushed.

I thought this post was a great read! I thought it was very interesting how you relate the Lean Six Sigma process to everyday experiences, in which this case was your dining out experience. Based on what you said, it seems as though Jiro Ono focuses on the principles of limiting the customer’s wait time, continuous improvement within his restaurant, and has a strong focus on quality of food. Although I think the workers at the restaurant are confident in the quality of their customer’s experience, I would agree with you that the pace of the service would lessen my personal satisfaction with my time at the restaurant. Personally, I like to take my time when eating out as well as using the experience to chit chat with those joining me. A question that came to mind based on the perfected system Jiro Ono has seemed to accomplish is do you think that his focus on perfection and speed would cause the employees around him to be stressed or even cause them burnout after an extended period of time? Overall, I really enjoyed this post!

Hi Ava – It’s hard to say if that system causes any stress. Everybody was moving at a purposeful pace, but it seemed calm and well organized. The team seems to have solid routines that they are practicing on a daily basis as they serve ccustomers.