Hear Mark read the post (subscribe to the podcast):

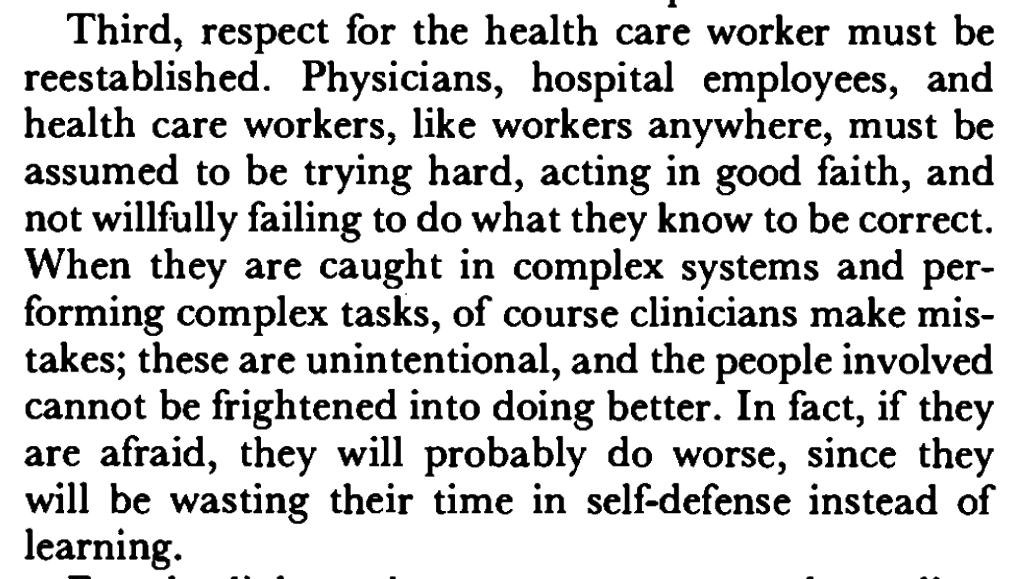

Back in 2012, I blogged twice about aspects of Dr. Donald M. Berwick's 1989 article in the New England Journal of Medicine titled “Continuous Improvement as an Ideal in Health Care.” The full text is only available to subscribers.

Here are the older posts that touched on some aspects:

We cited the article in our book Healthcare Kaizen, which has been out five years now, as I blogged about the other day.

As I posted on LinkedIn, another aspect of this article caught my eye when I was reviewing it the other day in advance of my talk at the Studer Group “What's Right in Healthcare” conference next week.

What I shared, along with the article excerpt:

From Don Berwick's 1989 NEJM article on Kaizen and Continuous Improvement in healthcare… we need to respect people. We can't frighten people into doing better. When we TELL people what to do, it creates natural defensiveness. That's one reason I've enjoyed learning about the “Motivational Interviewing” approach, as that creates a process for evoking change and tapping into intrinsic motivation. When people create their own change, that's so much more effective than being told what to do.

There's so much goodness in just this excerpt, not just the entire article.

Respect

Berwick writes:

“Respect for the health care worker must be reestablished.”

This seems non negotiable.

It's a shame if respect isn't there… and if it's not it, it should be reestablished or just “established” if it didn't really exist broadly in the organization before.

If we are looking to help healthcare leaders change (for example, if we hope they will embrace Lean and the Kaizen style of continuous improvement), that should start with respect and I sometimes don't live up to that ideal when I criticize healthcare executives for laying off employees, not focusing enough on patient safety, etc.

Assuming Good Intent

Berwick wrote:

“Physicians, hospital employees, and healthcare workers, like workers anywhere, must be assumed to be trying hard, acting in good faith, and not willfully failing to do what they know to be correct.”

Lean thinkers realize that lack of effort is usually not the problem. We assume that people want to do quality work, that they take pride in their work… our assumption of best efforts and good faith should include healthcare executives, right? If they don't know what else to do (for example, if they don't know alternatives to layoffs), should we be more willing to accept and respect their decisions, even if they're taking actions that are different than we would do?

Unintentional Mistakes

Berwick continues:

“When they are caught in complex systems and performing complex tasks, of course clinicians make mistakes; these are unintentional, and the people involved cannot be frightened into doing better.”

Lean thinkers realize that's true at the front lines. “Slips” and simple mistakes often occur due to distraction or fatigue. We're all human, so that's why the “respect for people” principle of Toyota and Lean doesn't blame people for their best efforts in a bad system. The “Just Culture” framework is helpful here too – and congruent with Lean.

Now, if a healthcare executive makes a strategic mistake or does something that goes against best practice leadership, is that different than a “heat of the moment” error or mixup by a clinician? Maybe it's more “just” to fault an executive for a “mistake” at their level, or to fault them for not learning from mistakes or not learning from others?

Is there a difference between a clinician knowing what to do and not doing it (for some systemic reason) and an executive who doesn't educate themselves about the best things to do?

Fear

Berwick finishes the paragraph:

“In fact, if they are afraid, they will probably do worse, since they will be wasting their time in self-defense instead of learning.”

Dr. Deming wrote about eliminating fear from the workplace. When we have a culture of fear, frontline employees will be far less likely to speak up about problems and ideas, which means far less improvement.

Do we think about fear in the C-suite? If an executive is fearful for their job, does that interfere with rational thinking and good decision making? Would we be as understanding if their fear is a fear of not getting their bonus because certain margin levels weren't met? We wouldn't want executives spending more time on “self defense” instead of learning and improving either, would we?

What do you think?

Please scroll down (or click) to post a comment. Connect with me on LinkedIn.

Let’s work together to build a culture of continuous improvement and psychological safety. If you're a leader looking to create lasting change—not just projects—I help organizations:

- Engage people at all levels in sustainable improvement

- Shift from fear of mistakes to learning from them

- Apply Lean thinking in practical, people-centered ways

Interested in coaching or a keynote talk? Let’s start a conversation.

This is a great article…as prescient 28 years ago as it is today! It is so interesting that this respect of the healthcare worker has been added to the lauded Triple Aim relatively recently yielding ‘The Quadruple Aim’.

Thanks for finding this article Mark!

Comment from LinkedIn:

Sarah Custack

I like your perspective on fear in the C-suite. These are uncertain times and understanding this fear should help our conversations to motivate action for improvement. Making the decision to develop and use a lean management system puts most leaders in unknown territory, and is not easy to do. It take a lot of courage.