A 2005 tour of the NUMMI plant revealed lessons about Lean that had little to do with tools and everything to do with leadership, learning, and respect for people. Twenty years later, these small, human moments still define what Lean really looks like in practice.

In 2005, I had the opportunity to tour the NUMMI plant in Fremont, California — the Toyota-GM joint venture that became legendary in Lean circles. I was reminded of this the other day, and I'll explain why in this post.

Like many visitors, I went in expecting to see tools, charts, and maybe some version of “Lean perfection.”

What stayed with me instead were a handful of small, human moments.

What a NUMMI Tour Taught Me About Lean Thinking

Over the course of that visit, I wrote a short series of posts I called the NUMMI Tour Tales. Each captured a specific observation: a broken escalator, a handwritten sign, aluminum foil, a gift shop, areas that weren't perfectly 5S'd, and a visual audit board.

Individually, they're simple stories. Together, they paint a clear picture of what Lean actually looks like when it's practiced as a management system — grounded in respect for people, discipline, and learning.

Twenty years later, these lessons still matter.

Hear Mark read this post — subscribe to Lean Blog Audio

1. Asking “Why” Before Spending Money

Early in the tour, we passed a massive escalator that had been shut down for years. Instead of quietly fixing it — or quietly ignoring it — NUMMI posted a large sign explaining why it wasn't repaired. The cost to fix it was about $120,000, and leaders felt that money could be better spent elsewhere. People could use the stairs or the elevator.

What struck me wasn't frugality for its own sake. It was transparency.

Someone had asked, “Why fix this at all?” and then took the time to explain that reasoning to employees and visitors. That's Lean thinking applied to capital spending — and to leadership communication.

Lean decisions aren't about being cheap. They're about thoughtful tradeoffs made visible.

This also reminds me of a classic joke from the late Mitch Hedberg:

2. Small Kaizen, Real Respect

In the body shop, workers spent hours each week cleaning welding racks by hand. One team member suggested wrapping part of the rack in plain aluminum foil. After a week, the dirty foil could be removed and replaced, reducing the cleanup time from four hours to one.

It wasn't high-tech. It wasn't expensive. It worked.

Just as important, the idea came from the front line. It was tested, adopted, and rewarded. That's what daily kaizen looks like when people feel safe to speak up — and when management assumes that the people doing the work are capable of improving it.

We now label that safety to speak up as “psychological safety.”

3. Explaining “Why,” Not Just Posting Rules

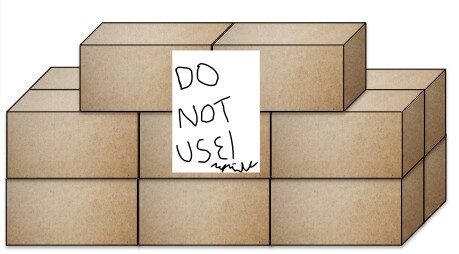

At many plants I'd seen boxes of parts labeled with a blunt command: DO NOT USE.

At NUMMI, a sign explained why: using those parts could result in brake failure and possible customer injury.

That difference matters.

Explaining “why” treats people like adults. It connects decisions to customers and safety, not authority. It also reduces the pressure to “just make it work” when the line is under stress.

This is respect for people made visible — and it's inseparable from quality and safety.

Why was I reminded of all of this? I was recently visiting a Kentucky distillery and their production area had bags of German malted rye that had a sign saying, “DO NOT USE.”

No shouty exclamation point. But no reason why, either.

4. Pull Thinking Beyond the Factory Floor

Even the NUMMI gift shop reflected Lean thinking. No piles of inventory in the lobby. Instead, display items were shown, and visitors could “pull” items by phone to be delivered later.

Tour guests didn't have to carry items around. Inventory was minimized. Flow was improved.

Was it perfect? Probably not. But the mindset was there: apply Lean thinking everywhere, not just where it's most obvious.

Lean wasn't a department. It was a way of thinking.

5. Improvement Without the Myth of Perfection

NUMMI would score highly on most visual management and 5S checklists — but it wasn't flawless. On the tour, you could see items out of place or shadow boards missing tools.

What stood out was how openly the NUMMI leaders talked about this. They admitted that they had gotten away from regular standard work audits and needed to recommit to them.

That honesty mattered.

Lean organizations don't pretend to be perfect. They aim for perfection while acknowledging reality. They talk openly about gaps without defensiveness or blame. That openness is what allows improvement to continue.

6. “You Get What You Inspect” — Not What You Expect

(Standard Work as a Living System)

The final NUMMI Tour Tale tied everything together.

NUMMI emphasized that standard work and 5S are not one-time exercises. They are living systems that require ongoing leadership attention. Visual audit boards showed which jobs had been audited and which hadn't. Group leaders were expected to audit one job every day.

Their mantra stuck with me:

“You get what you inspect, not what you expect.”

This wasn't about policing people or catching mistakes. It was about leader presence, coaching, and reinforcing that standard work actually matters.

If leaders expect practices to stick without regularly going to the gemba — without genchi genbutsu — they're practicing wishful thinking, not Lean management.

Psychological safety does not mean the absence of accountability. It means accountability is exercised thoughtfully, consistently, and without fear.

What Changed After NUMMI Closed — and Why It Matters

In 2010, NUMMI shut down. A few years later, the same building became the first factory for a very different automaker – Tesla.

That physical continuity makes the contrast unavoidable.

After NUMMI closed, the same Fremont building became Tesla's first factory. While the physical plant remained, the management system did not. Reports and former-employee accounts suggest a shift away from Toyota's emphasis on built-in quality, leader discipline, and daily problem solving toward a mindset that prioritizes speed, heavy automation, and fixing defects after the fact.

Where NUMMI focused on stopping to address problems and reinforcing standard work through leader presence at the gemba, Tesla has been described as relying more on end-of-line inspection, rework, and heroic efforts to meet aggressive production targets. And I've been told that Elon Musk tells people not to say anything about Toyota practices — and that if you were a previous NUMMI employee who got hired by Telsa, you keep you mouth shut about that.

The contrast reinforces a key lesson from NUMMI: buildings and technology don't create quality–culture and leadership behavior do.

What Still Defines Lean Thinking

Looking back, these stories were never really about escalators, foil, or gift shops.

They were about:

- Asking better questions before acting

- Respecting people enough to explain decisions

- Creating conditions where small ideas are welcomed

- Designing systems thoughtfully, not heroically

- Reinforcing culture through daily leadership behavior

Today, we have clearer language for something that was present at NUMMI but rarely named in 2005: psychological safety.

People at NUMMI were willing to question spending, suggest improvements, admit backsliding, and prioritize customer safety because the culture made those behaviors possible.

That's still the real work of Lean.

And it's still fragile.

What Still Defines Lean Thinking Today

Looking back, the NUMMI tour lessons were never really about escalators, aluminum foil, or gift shops. They were about leadership behavior, transparency, and systems designed to help people succeed.

NUMMI demonstrated that Lean is not a collection of tools or a pursuit of perfection, but a management system grounded in respect for people, psychological safety, and daily discipline. When leaders explain why, encourage small improvements, inspect what matters, and admit gaps openly, improvement becomes sustainable. Those principles still define Lean thinking today–and they remain just as fragile as they are powerful.

Explore the original NUMMI Tour Tales:

- NUMMI Tour Tale #1: Why Fix the Escalator?

- NUMMI Tour Tale #2: The Power of Reynolds Wrap

- NUMMI Tour Tale #3: The Power of Why

- NUMMI Tour Tale #4: The Pull Gift Shop

- NUMMI Tour Tale #5: Nobody Is Perfect

- NUMMI Tour Tales #6: “You Get What You Inspect”

Please scroll down (or click) to post a comment. Connect with me on LinkedIn.

If you’re working to build a culture where people feel safe to speak up, solve problems, and improve every day, I’d be glad to help. Let’s talk about how to strengthen Psychological Safety and Continuous Improvement in your organization.

A comment on LinkedIn: