For a long time, it's bothered me that organizations typically react to a mistake with punishment. This is even more annoying when the phrase “hold people accountable” is used as a polite or passive-aggressive way to say “blame and punish people.”

This happens a lot in healthcare, unfortunately.

As I've been editing the manuscript for my upcoming book, The Mistakes That Make Us, the topic of mistakes has been on my mind a lot. I blogged about my own mistakes this week and also blogged about medical mistakes that harm patients.

A thought and a phrase occurred to me on Friday:

“You can't punish your way to perfection.”

I thought, “I can't be the first person to put it that way,” but various Google searches bring up nothing.

Punishing individuals for making mistakes doesn't reduce mistakes over time.

Some people think that punishment drives improvement.

There's a train of thought out there that's unfortunately still far too common:

- Mistakes are bad

- Bad employees make mistakes because they're careless or inattentive

- Therefore, we must punish people for mistakes

- If we didn't punish people, we'd be giving permission to make more mistakes (and mistakes are bad)

If punishing people actually reduced mistakes over time, I think we'd see EVIDENCE of success with that strategy. But we don't.

If punishing people for mistakes actually worked, we'd be in a mistake-free world by now.

Here's the problem with the punishment approach:

- Almost all mistakes are driven by systemic factors and causes

- Employees realize it's unfair to be blamed for most mistakes

- Punishment and the fear of punishment doesn't reduce mistakes… it reduces REPORTED mistakes

- People learn they must get better at hiding or covering up mistakes — or shifting blame to others

- Employees channel their creative energy into that instead of developing actual mistake-proofing methods

We know examples of organizations that react constructively to mistakes.

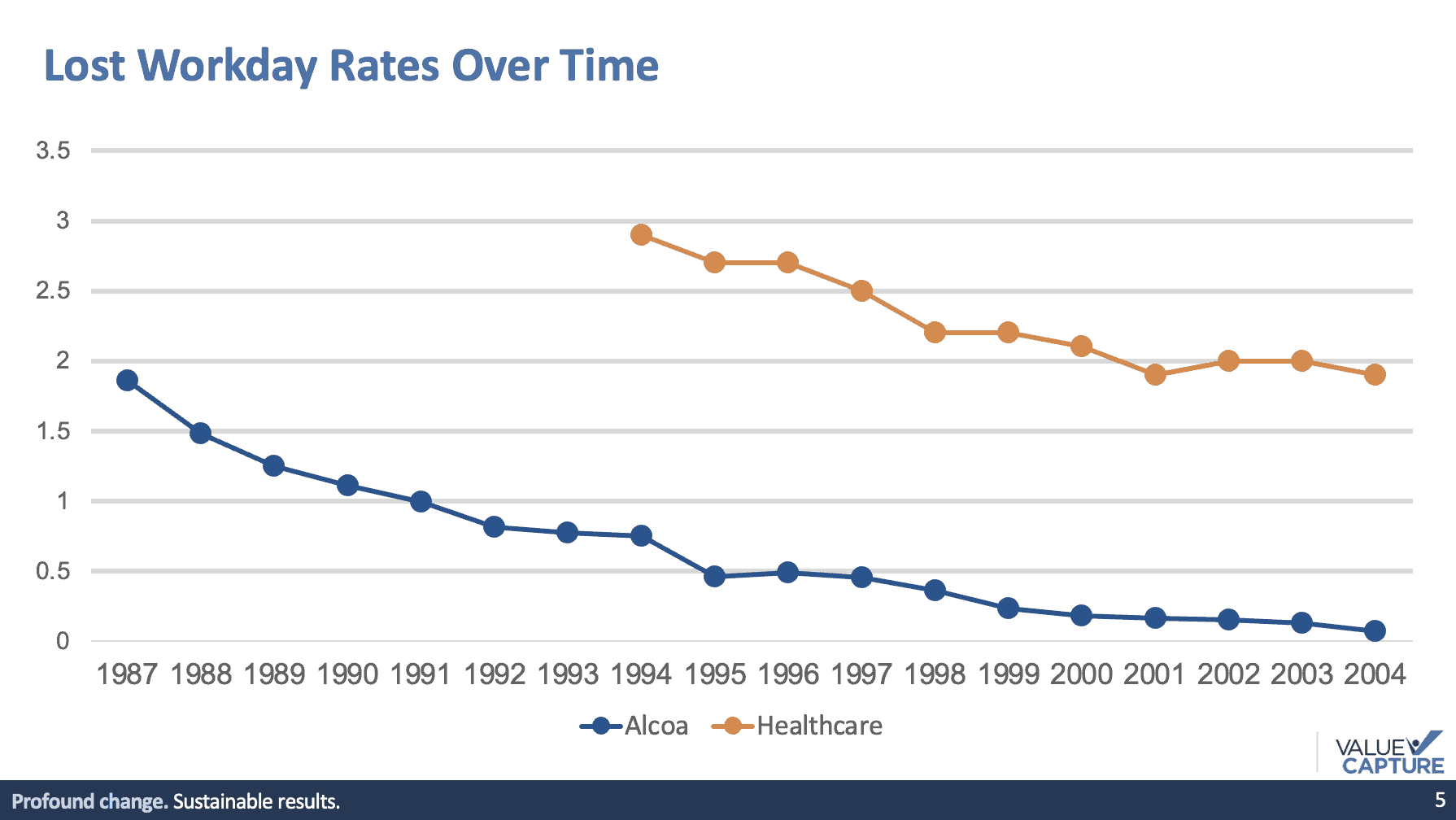

By comparison, Alcoa, under Paul O'Neill's leadership, saw dramatic reductions in employee harm — injuries and harm are one form of mistake.

Their improvement resulted from of a culture of openness, transparency, learning, and improvement. Alcoa didn't improve so much because O'Neill and other leaders there were better at punishing people when safety incidents did occur.

In 1987, Alcoa's performance was better than average. Their injury rate was 63% lower than the typical U.S. workplace at the time. Yet they were still driven to improve toward O'Neill's goal of zero harm.

Healthcare, having more of a punishment-based culture, had much HIGHER employee injury rates and a slower rate of improvement. If you can prove that this has changed in the last 19 years, please let me know.

It's been almost 25 years since the famed report “To Err is Human” was published.

To Err Is Human breaks the silence that has surrounded medical errors and their consequence–but not by pointing fingers at caring health care professionals who make honest mistakes. After all, to err is human. Instead, this book sets forth a national agenda–with state and local implications–for reducing medical errors and improving patient safety through the design of a safer health system.

Leaders in the patient safety movement (or the quality movement) preach that punitive responses to mistakes and harm are ineffective if not counterproductive.

Transparency, not punishment, reduces medical mistakes

Twenty-five years ago, public health expert Lucian Leape testified to Congress that the greatest impediment to medical error prevention is that we punish people for mistakes. Despite a shift toward safer systems, Leape's assessment remains true.

Also from that article:

As argued by James Reason, a pioneer in the science of human error, most catastrophic errors are predictable and preventable, made by well-intentioned people working in poorly designed systems.

I'm not saying that I invented the idea that punishing mistakes is counterproductive. But the phrase “you can't punish your way to perfection” seems novel.

How many healthcare organizations today truly have a “just culture“? How many have created conditions for high levels of psychological safety that make it safer for people to speak up about mistakes, problems, and improvement ideas?

Why are there just some unicorn-like pockets of excellence, where the right kind of culture (including effective problem solving) can almost completely eliminate certain types of medical mistakes and harm. And why doesn't that excellence (and the practices that drive it) spread more quickly?

To summarize:

- Punishing people for mistakes doesn't reduce mistakes

- Punishing people for mistakes is counterproductive

- There's no evidence that more punishment leads to more improvement

- In fact, the opposite is true… organizations that react constructively to mistakes, focusing on learning instead of punishment, end up improving more

If you claim to want “evidence-based” management, you have to admit that the blame game should be over. Punishment doesn't work. We need a better way.

Feel free to comment about this post over on LinkedIn since the comments functionality is currently broken on my blog…

Edits and Additions:

Scott Leek posted a great comment on the LinkedIn post:

“The premise of the argument is noble in its pursuit but misguided. Punishment, in an organization, or more broadly in society is not now, nor ever intended as a driver of improvement. Instead, the purpose of punishment is to cleanse ourselves, our organization, or our society of fault, blame, or guilt. Mary Surratt's execution had little to do with improvement and everything to do with human nature's desire to purge and cleanse. Punishment is viewed as purification, not improvement. Though people do get them confused. There is a school of thought that refers to this as ‘monkey brain.'”

My first reply (and you can read the rest on LinkedIn):

Interesting. I think there is an element of the “punishment helps” mindset where people think the threat of punishment will make people be more careful, which leads to fewer errors.

Great point though about people using punishment as a way to absolve themselves of blame.

One reason Dr. Deming's message was never really that popular is that he emphasized that senior leaders are responsible for the system… and therefore responsible for the results that are driven by the system.

When leaders have the power to blame others… they will do so. It's human nature (look at the story of Koko the Gorilla, who blamed her cat for tearing a sink out of the wall). But I doubt Koko or the human handlers punished the cat. They probably didn't punish Koko.

How could a healthcare CEO sleep at night feeling responsible for all of the mistakes and harm? It's easier, as a survival strategy and a mental health strategy perhaps, to just blame others

Please scroll down (or click) to post a comment. Connect with me on LinkedIn.

Let’s work together to build a culture of continuous improvement and psychological safety. If you're a leader looking to create lasting change—not just projects—I help organizations:

- Engage people at all levels in sustainable improvement

- Shift from fear of mistakes to learning from them

- Apply Lean thinking in practical, people-centered ways

Interested in coaching or a keynote talk? Let’s start a conversation.

![When Was the Last Time a Leader Around You Admitted They Were Wrong? [Poll]](https://www.leanblog.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/Lean-Blog-Post-Cover-Image-2025-07-01T212509.843-238x178.jpg)

![When Was the Last Time a Leader Around You Admitted They Were Wrong? [Poll]](https://www.leanblog.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/Lean-Blog-Post-Cover-Image-2025-07-01T212509.843-100x75.jpg)

[…] Beyond Discipline: You Can’t Punish Your Way to Perfection – Mark Graban explains why punishment doesn’t work and why we need a better way. […]

Comments are closed.