TL;DR: Emails and warning signs rely on memory and attention. Point-of-use reminders–and better yet, mistake-proofed systems–are far more effective at preventing errors, as a simple condo trash chute failure illustrates.

I often write and speak about how warning signs (or cautions) are not effective at preventing mistakes, errors, and problems. See this recent post about this: Signs Are Not Mistake-Proofing: Hospital Hallways Edition.

From a Lean perspective, this is a classic example of relying on information instead of designing a system that makes the right action the default.

And to prove that I've been writing about this for a long time, here's a post from 2007: Signs are Not Error Proofing: Electrical Circuit Breaker Edition.

By the way, the words “mistake” and “error” are synonyms to me. And Prof. John Grout, an expert on this topic agrees (or he convinced me that the meanings are the same).

Why Signs (and Emails) Are Weak Forms of Mistake-Proofing

Signs, generally, are an ineffective attempt at mistake-proofing (or poka-yoke in Japanese). When we see signs in a workplace that say things like:

- Warning

- Caution

- Watch out

- Please remember

- Don't forget

- Danger

Those signs are all screaming out to us as an opportunity to try something that's more effective. Signs can be ignored. It's better to change the process or the system (including the equipment or software) so that it's easier to do the right thing and harder (if not impossible) to do the wrong thing.

That said, sometimes a sign is the best you can do (or the best you've figured out to do… for now).

One example of mistake-proofing that's better than a sign can be found at In-N-Out (and other fast food / quick service restaurants), as I blogged about here:

The photo is of the food, but the main point was the difference between a trash can (at other restaurants) that has a sign that yells at you about not throwing out trays or baskets, like this:

In-N-Out has a trash area where the trash holes (is that the technical term?) are big enough for things they WANT you to throw out (like disposable cups) while being too small for their trays to fit:

Mistake-proofing (the smaller hole) is FAR more effective than the warning sign.

A Real-World Example: The Condo Trash Chute Breakdown

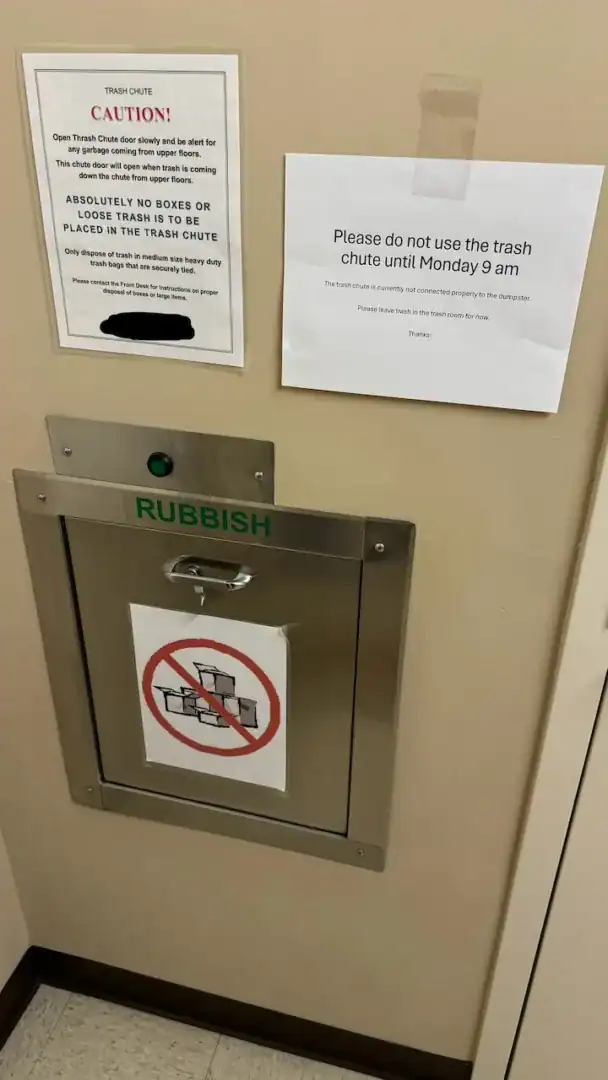

My wife and I live in a high-rise condo and there is a trash chute in a small room that's just off the common-area hallway outside our unit.

We received an email on Sunday, at about 8 am, from the front desk security guard that read, in part:

“We are currently having an issue with the trash chute, it is not properly connected to the dumpster, and I would like to ask you to please hold off on using the trash chute until tomorrow (Monday, the 18th) as much as possible so we can get things fixed. Thank you.”

The maintenance manager comes in on Monday morning. It wasn't worth him making a separate trip to the building on a Sunday.

When Systems Rely on Memory, Failure Is Predictable

Later that day, probably after dinner, out of habit, I:

- Noticed the trash was full

- Grabbed the bag

- Carried it to the trash room

- Dropped it down the chute

“Oh no!”

That was my immediate reaction. The bag was barely off the end of my finger tips, but it was too late.

I had forgotten about that request to please not use the trash chute until Monday morning.

Point-of-Use Signals Beat After-the-Fact Communication

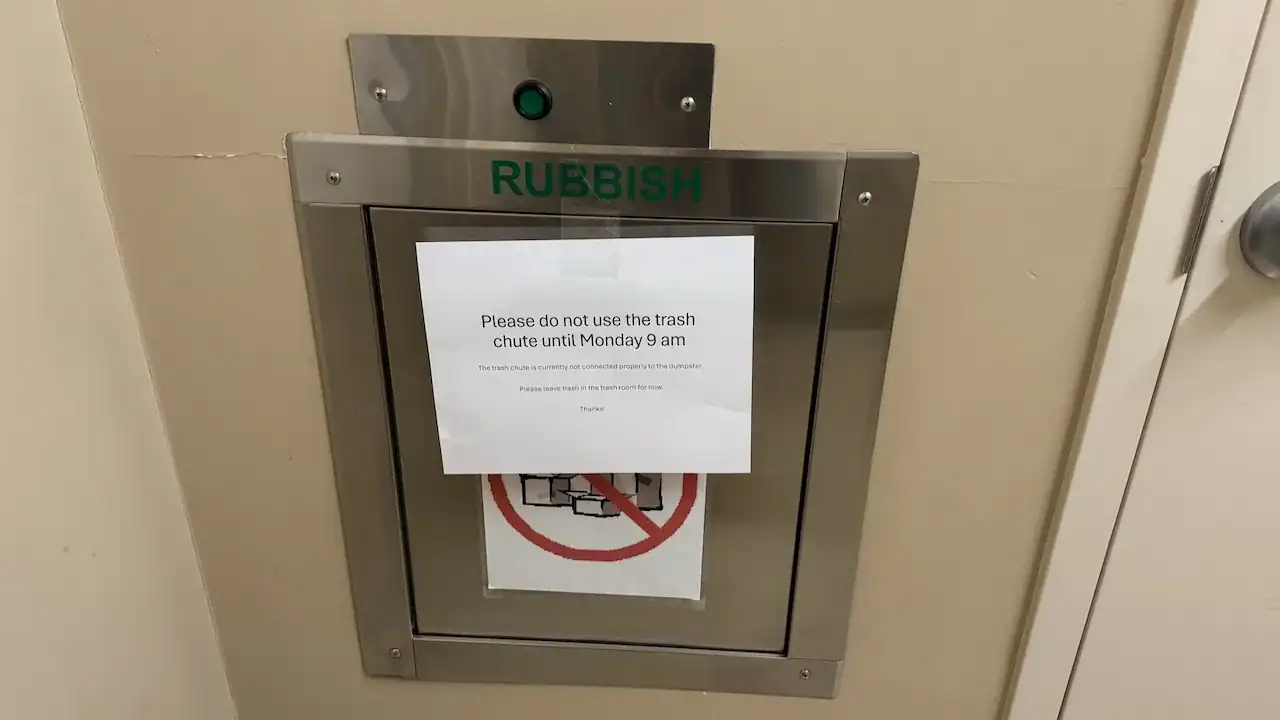

Here's what it would have looked like if they had put a SIGN on/over the trash chute handle, which would have been a “point of use” reminder. It wouldn't have relied on my memory. I bet I'm not the only one who forgot. The sign over the trash chute door handle would have been impossible to miss. Unless you taped the door shut, the sign isn't perfect mistake proofing.

But I think it would have been better than an email. Again, I wish I had thought of this on Sunday morning.

If the sign had been placed NEAR the trash chute (as I also simulated here on Tuesday, shown in the photo below), it might have been easily missed by someone moving on autopilot. If you're doing this all the time, you're probably going off of muscle memory as you are using your full cognitive powers.

I think the existing sign on the door says “No boxes” — in a way that's language-neutral. My sign is admittedly not. The sign above is quite wordy, but it's good to have those rules posted for handy reference instead of having to find the “rules and regulations” document online.

Maybe a better sign for the “don't use the trash chute today” purpose would have been a red circle/slash that implies “DO NOT USE” that could have been placed over the handle.

Why Explaining “Why” Still Matters

Even though my sign is only in English, I think it gets a “plus” for trying to explain WHY this directive of “do not use” was being given and how long it would be in effect.

Here's a blog post about explaining why that's a story from my 2005 visit to the NUMMI plant:

Having a sign would have also avoided the “failure mode” of people not checking their email on Sunday (I know, I should take a break from peeking at my phone).

Now, somebody would have had to print out a sign for each floor in the building. I would have been happy to help out with that… had I thought of it. But I didn't.

Next time.

Conclusion: Mistake proofing is better than a point of use information sign. But a sign is better than an email or a memo.

What was the Root Cause of the Problem?

There's also, perhaps, a root cause to the problem of “trash chute is not properly connected to the dumpster.”

I wouldn't ask, “Who screwed that up?”

I'd ask questions like, “How did that occur?” and “What can we do to prevent that?” Why did that happen?

It could be an opportunity for a “5 Whys” analysis (although I tend to call that the “Many Whys,” as I've blogged about here:

From Memory and Compliance to System Design

Emails, memos, and warning signs all share the same weakness: they rely on people remembering, noticing, and complying–often while operating on autopilot. In this condo trash chute example, the failure wasn't a lack of communication. The message was sent. The problem was that the information wasn't available at the moment of action.

That's why point-of-use information matters so much in Lean thinking. A sign placed directly on the trash chute handle wouldn't require residents to recall an email from hours earlier. It would interrupt muscle memory and make the abnormal condition visible right when a decision is being made.

Of course, a sign is still a workaround–not true mistake-proofing. The ideal solution would be a physical or mechanical countermeasure that prevents use of the chute when it's disconnected. But when that's not immediately possible, designing a better system for communication at the point of use is far more effective than relying on inboxes, reminders, or good intentions.

Design the System So the Right Action Is the Easy Action

This wasn't a story about someone being careless or not paying attention. It was a predictable outcome of a system that depended on memory instead of design.

When mistakes happen, the most useful question isn't “Why didn't people follow instructions?” It's “What about the system made the mistake easy?” In this case, the answer points toward better point-of-use communication–and eventually, better mistake-proofing–rather than more emails or stronger wording.

Just as important, responding this way reinforces psychological safety. When leaders treat mistakes as signals of system weakness instead of personal failure, people are more willing to speak up, suggest improvements, and help prevent the next problem.

Mistake-proofing beats signs. Signs beat emails. And all of them beat blame.

What everyday examples have you seen where a small design change would have prevented a very human mistake?

If you’re working to build a culture where people feel safe to speak up, solve problems, and improve every day, I’d be glad to help. Let’s talk about how to strengthen Psychological Safety and Continuous Improvement in your organization.

There was another problem with the trash chute — the next Sunday.

The front desk team graciously accepted my suggestion to post signs on each floor.

I guess the next question would be the root cause of the trash chute problem… maybe I can help with the problem solving…

Update: I think they got to the root cause of why the trash chute couldn’t be used. It was a slightly different problem each time, but I think it’s now resolved.