The Wall Street Journal published a fascinating article back in November 2020:

Stephen Curry's Scientific Quest for the Perfect Shot

The links I've used should allow you to read the article even if you're not a subscriber.

On Wednesday, I'm going to be releasing a Lean Blog Interviews podcast with Prof. Elliott Weiss, from the Darden School of Business, who had blogged about this article. We'll be talking about the article (and many other topics) in the episode.

The subheadline of the WSJ piece reads:

“The NBA's best shooter decided the basket was too big. He used technology to make it smaller. The goal: ‘swishes within swishes.'”

That sounds like reducing variation to me… that's got me intrigued. Let's keep reading.

Embed from Getty ImagesFirst off, what are the diameters of an NBA basketball compared to the hoop?

- Ball: 9.52 inches (24.18 cm)

- Hoop: 18 inches (45.72 cm)

So you're telling me that the hoop is almost twice as wide as the ball? That's not how it's seemed when I've played basketball (badly) in my lifetime.

Using Data to Rethink Basketball Shots

A cancer researcher who was pursuing a PhD in bioinformatics, Rachel Marty Pyke, used software to analyze over 20 million basketball shots and declared:

“We conclude by encouraging coaches and players to re-evaluate their largely anecdotal assessment methods and implement more effective, data-driven methods to enhance shooter development,” Pyke wrote.

Lean thinkers realize that “the way we've always done it” doesn't make that method right.

“Data-driven methods” will likely beat anecdotal analysis any time — if the data are statistically meaningful. Many people worship at the altar of “data driven,” but some “data-driven decisions” are still “bad decisions.”

But Steph is Already the Best!

Stephen (Steph) Curry has already made more 3-point shots than any player in NBA history. He also makes them at a very high rate, shooting 42.9% for his career (the league average this year is 34.9%).

It's amazing that he's still driven to get better. Continuous improvement leads to sustained excellence.

As the computer analysis showed, a shot doesn't have to be dead-center in the hoop to go through.

A shot that strays nearly 5 inches away from the center of the hoop in either direction can still be a swish.

A Disgression Into Manufacturing Speak

Thinking of manufacturing quality, there's an opportunity to think beyond “good / no good” (did the ball go in or not?). Any shot from behind the 3-point line that goes in is worth 3 points. You don't get more points for being more on-center.

But, in manufacturing, being closer to the center of the dimensional specifications IS better. When I worked in a General Motors engine plant, one critical dimension was the diameter of the engine block cylinder bores. There was a nominal spec — ideally, all parts would have been the exact same size.

But, there's ALWAYS variation. Tighter variation, smaller variation, is better.

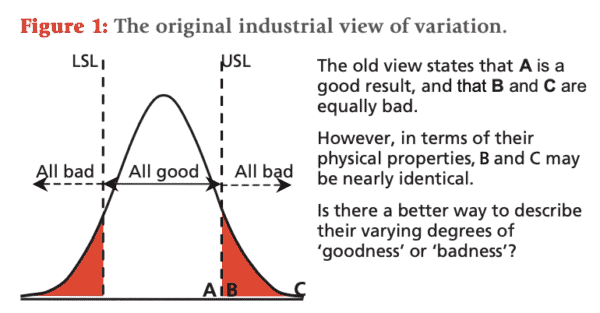

The old view of quality was that “anything inside the specification limits is good.”

Enter the “Taguchi Loss Function,” which illustrates the economic loss of parts that are “off center.”

Here's an article on the topic: “Meeting Specifications is Not Good Enough–The Taguchi Loss Function.”

Here is a figure from that article. The normal distribution might also represent how a basketball shot is centered in the rim. The “all good” is 3 points, “all bad” is nothing.

Concluding thoughts from that article:

What is clear is that several different approaches to the subject arrive at strikingly similar conclusions, as follows:

• Variation costs money, even when everything appears to meet specifications

• Reducing variation always reduces costs

• Not all variables have an equal impact on costs. Some are very significant; others are not.

Variation costs money — whether that means engine block cylinder bores that are too big (or too small) or basketball shots headed toward the hoop.

The Taguichi Loss Function shows us that the loss INCREASES as we get further from center. Instead of “good/no good,” we need to think about quality as “distance from target.”

Steph Curry adopted that view.

Back to the Court

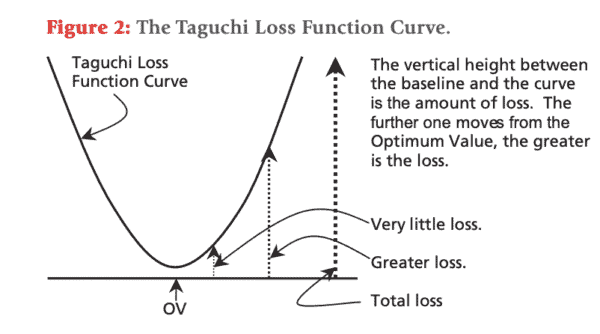

Let's look at the basketball analysis… this looks like a form of the Taguchi Loss Function. A shot that's dead center has almost an 80% chance of going in (there are other factors involved, such as the height, speed, and spin on the ball).

You can see how the odds of an off-center shot going in decrease significantly (and non-linearly) as you get further from center. A shot to the far left or far right could still go in if it takes some lucky bounces. Again, a shot counts the same if it's a “swish” or if it bounces off the rim and backboard multiple times.

Shots that are a little off-center as nearly as likely to go in…

“But when you get to four or five inches,” said John Carter, the company's CEO, “it's like falling off a cliff.”

So, being able to more reliably hit the center of the hoop means your shooting success rate goes up.

Curry learned to look at the variation in his shots (and technology makes this much more measurable):

“To make even more threes required [Curry] to accept that not all made threes were alike.”

General Motors had to accept that “not all in-spec engines were alike” (and that new concept caused many quality arguments in my plant).

Shooting Drills and Measurement

From the WSJ:

Curry would listen for the instant verbal feedback on his left-right locations and learn whether a shot met his standards. He wasn't relying on sight to determine the quality of his shot. Instead he waited for the sound of a computerized voice.

There's also the “forward-back” locations to be considered — I wonder how that was taken into account?

As Curry's long training sessions continued, they could see…

Even if he made a bunch of shots in a row, they could tell he was tired if the ball veered an inch or two off target.

Back to the fights at GM — quality engineers would want to “stop the line” if critical dimensions were drifting away from center (they were “out of control”), but management would say “keep the line running, those parts are still good” because they were only thinking in terms of good/bad specifications.

How Does He Adjust? Does He Overadjust?

The article doesn't get into the detail of how Steph adjusts to the feedback that can come from each practice shot.

Students of W. Edwards Deming will probably be thinking of his famed “funnel experiment” that shows what happens when we overadjust in response to variation — constant adjustment based on the last part ends up INCREASING variation, which is costly.

Here is a great simulator for the funnel experiment, go check it out.

There's ALWAYS going to be variation, including in Steph Curry's Hall-of-Fame shooting.

If the computer tells Steph “+3” for a shot, he can do a number of things that are like the funnel experiment.

- Shoot the next shot exactly the same

- Conciously think “aim 3 inches to the left”

Hopefully, he does the first. Doing the second will INCREASE his variation, which will mean more missed shots. The second action is an example of “tampering” with the system.

He should be focusing on decreasing variation by focusing on his shooting “system” — including having more consistent body mechanics (more consistent process leads to more consistent results) and reducing the variation in his mechanics that's triggered by stress or fatigue. The article describes how he aims to practice in near-game-like conditions, with an elevated heart rate, etc.

I'd love to see data that shows if Curry is “more on center” or “less on center” with his practice shooting and his game shooting.

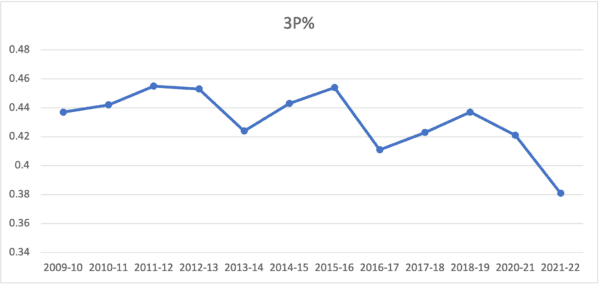

It's easier to look at the results… a line chart of his 3-point shooting percentage by season (removing the 2019-2020 season in which he played just five games):

Many might look at this chart and say “But his shooting has gotten worse two years in a row!!”

As the statistician Don Wheeler says, “No data have meaning without context.”

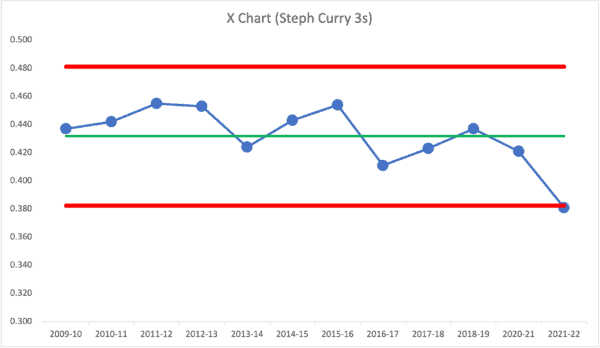

We can look at this data as a “Process Behavior Chart“:

We know we shouldn't react to every up and down in a business measure, this included.

That said, this season is his “lowest 3 point shooting percentage ever.” That statement alone doesn't mean that it's statistically significant… but that last data point (this incomplete 2021-22 season) is a bit below the calculated lower limit. That makes it a statistical signal where we would then be well served by asking “what changed in the system?”

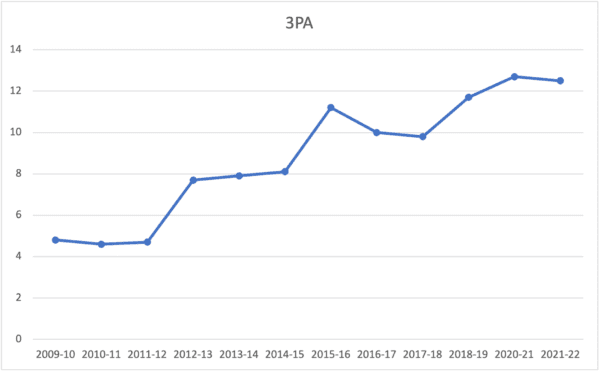

Looking at the data, Curry is taking MORE three-point shots the last two seasons.

He might be taking shots from further out and it could be a conscious decision that taking more shots from three is better than only taking the ones you're most likely to make. There's a general upward trend in shots taken that goes with a downward trend in percentage made — correlation or causation?

That goes to show why we shouldn't fixate too much on any single metric. Points scored matters and games won is the end result they're looking for.

Is Curry's training helpful or not? The answer is “we don't know for sure.”

From two weeks ago:

Golden State Warriors' Stephen Curry hits winner at buzzer, admits shot needs to improve

“I know I got to shoot the ball better,” Curry said. “I want to shoot it better, and I'm gonna shoot it better. … I obsess over the shooting numbers because that's what I do and that's what I work on. When you don't reach those levels, it's frustrating.”

Is he obsessing too much? Overadjusting too much? All I can say is that it's a possibility.

Does continuous improvement effort lead to continuous improvement results? Not always.

Why is he in a shooting slump? Age? Not enough days off? Lack of practice time?

Steph says:

Curry said he doesn't have a clear explanation as to why he is shooting poorly. There is a belief that the catalyst for his slump dates back to early December, when Curry was chasing Ray Allen's all-time 3-point record. But that's not all there is to it, according to Curry. What exactly it is, though, is more elusive than anything else.

“I'm just missing shots,” Curry said. “There's no reason, other than you just miss shots.”

This article from five days ago has theories:

Warriors mailbag: What's at the root of Steph Curry's shooting slump?

According to a recent report from the Athletic, Curry developed a habit of launching off his toes and not the balls of his feet, which likely contributed to the slump

That would be a body mechanics issue.

From the Athletic story:

The discovery [of launching from his toes] paid immediate dividends. His shots started falling like normal in practice. The swishes came back. So did the pretty rotation on his ball. His balance corrected with the added burst. The oomph he regained behind the follow-through gave him much better control over the ball.

And that has nothing to do with the computer analysis :-)

These articles all use a ton of words to try to explain the statistical trends, when a simple line chart would be so much more efficient — and effective. I wonder if the writers are held to a word-count performance measure and quota? ;-)

What Can We Conclude

Steph Curry's shooting percentage is down. Why? We don't know for sure. It's a complex system.

We DO know that this season (to date) is a “statistical signal” worth investigating. Maybe they found the “root cause” in his mechanics. We could look at monthly data to see the impact of that adjustment more quickly.

Did the shooting drills as described by the WSJ help his shooting? Maybe. Maybe not. Shooting percentages are down, but it's possible they would have been even lower without that new training approach that focused on left/right not the difference between using the toes or balls of the feet.

Process improvement is difficult. Even when being data-driven, finding or proving cause-and-effect is a real challenge.

Please scroll down (or click) to post a comment. Connect with me on LinkedIn.

Let’s work together to build a culture of continuous improvement and psychological safety. If you're a leader looking to create lasting change—not just projects—I help organizations:

- Engage people at all levels in sustainable improvement

- Shift from fear of mistakes to learning from them

- Apply Lean thinking in practical, people-centered ways

Interested in coaching or a keynote talk? Let’s start a conversation.