In case I'm “burying the lede,” as they say in journalism, my new book, Measures of Success, is available for purchase as an “in-progress” eBook.

Today, I'm giving a keynote talk at the Lean & Six Sigma World Conference being held in Las Vegas. I don't normally attend or speak at “Lean Sigma” events, but I had an opportunity to give a new talk that touches on two of my favorite themes in recent years – the need to apply statistics and psychology to our “Lean Management” practices or Six Sigma or whatever. The other keynote talk is being given by Captain Chesley (“Sully”) Sullenberger, so I'm really excited to hear him speak and hopefully get to meet him.

In this post, I'll go through the main themes of my talk, and you can see the slides and get more information here. There's also a video recording of a practice “webinar” there on my page, below, or via YouTube.

Hear Mark read this post — subscribe to Lean Blog Audio

Deming Before Lean

Many people who are familiar with my work would frame me as a “Lean person” or a “Lean healthcare person.” I don't hate that label, but I'd first consider myself a “Deming person.” Before I ever got introduced to anything about Toyota, I was introduced to Deming's work because my dad attended a Deming four-day seminar through his job at Cadillac and he had a copy of Out of the Crisis on the shelf.

When I was graduating from college, I didn't really want a job in the auto industry after growing up near Detroit and hearing what the environment was like. I wanted a more modern workplace. But, I got into the interviewing process with GM and learned of an opportunity with GM Powertrain at their Livonia Engine Plant. It was my hometown, and the plant was one that was supposedly influenced by Deming. They had a different labor agreement and operated under something called “The Livonia Philosophy.”

Click the image for a larger view.

This sounded great, and I took the job.

It didn't take long to realize that the Deming stuff had been championed by a former plant manager, who had since been promoted a few levels. The Deming philosophy wasn't embraced by the current plant manager or his managers under him. Deming passed away in 1993, and that might also have been when The Livonia Philosophy was pronounced dead.

The Livonia Philosophy, as good as it sounded, was reduced to a bunch of posters and slogans on the wall. Oh, the irony. Actual irony, unlike the Alanis Morrisette song that was popular around that time.

Why is Deming relevant today, almost 25 years after his death? When I've traveled to Japan, including my most recent trip last month, Deming is still mentioned by organizations there, including some in healthcare. Deming was the inspiration and foundation for their quality movement.

Former Toyota chairman Shoichiro Toyota once said:

“There is not a day I don't think about what Dr. Deming meant to us. Deming is the core of our management.”

I hope that's true for Toyota leaders today, as I think Deming was very far ahead of his time. He was a revolutionary and sometimes it takes a long time for heresy to be accepted as truth.

What's Missing in Lean Daily Management?

These days, we see many organizations embracing and adopting what they call “Lean Daily Management” or a “Daily Management System” or something like that. This is especially trendy in healthcare.

Lean Daily Management is a great concept, and it's hard to argue with methods like huddles, Gemba visits, improvement boards, aligned and balanced metrics, and more. But, I've also seen too many organizations that copy a tool (like a specific huddle board format from ThedaCare) without copying mindsets and philosophy. It's one thing for managers to get out of their office to attend a huddle. But, they also have to make sure they aren't blaming employees for quality problems or pushing all of the improvement responsibility onto them.

As I've written about, I think Lean Daily Management practices would be strengthened by best practice statistical methods, such as the “Process Behavior Charts” of Donald J. Wheeler (something that's the core of my upcoming book Measures of Success – see more about this at the bottom of this post).

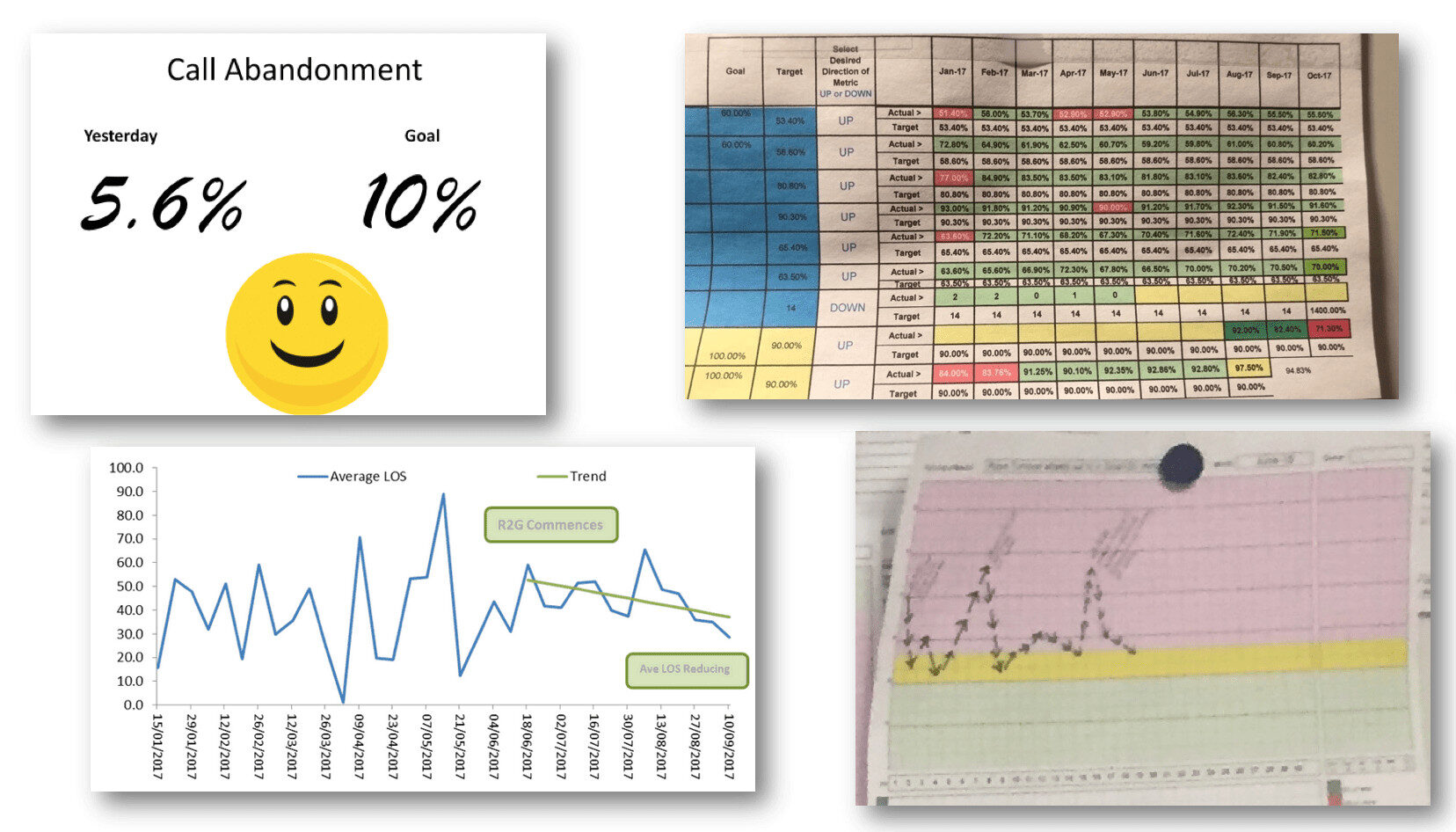

Too many huddle boards (or strategy deployment walls) incorporate what are, frankly, bad statistical methods, as illustrated below:

These methods include:

- Using single data points (or two data point comparisons)

- Comparisons to targets without understanding trends

- Faulty trend analysis, such as linear trend lines

- “Bowling charts” with red/green color coding

- Run charts with red/green color coding

In those methods, there's too much focus on the question of “are we hitting our targets?” and not enough understanding of the difference between signal and noise in our metrics. The above methods don't really help us answer the important questions of “are we improving?” or “how can we improve?”

Process Behavior Charts Are Better

As I've blogged about (and am writing about in Measures of Success) Process Behavior Charts are a simple, effective, and helpful method that anybody can use. As Wheeler says, Process Behavior Charts are a mindset, with some tools attached. That hopefully reminds you of Lean. Lean is a mindset, with some tools attached.

A Process Behavior Chart helps us:

- Separate signal from noise

- Understand when to ask “what happened?” and when not to overreact to a single data point

- See meaningful signals or trends or shifts in our performance

- Prioritize improvement work and investigations into causes of poor performance

- See If system changes lead to significant changes in our metric and

- See if our changes are being sustained

But, having a method, like Process Behavior Charts, that's technically correct, doesn't mean much if we can't get people to embrace the new method.

Being Technically Correct Isn't Enough

What if managers don't see anything wrong with the way they are managing? A new method can be a tough sell if it solves a problem that people don't see… or if it solves a “problem” that people don't consider to be a problem.

Being right doesn't mean others will go along.

This is a change management challenge, and we shouldn't blame people for being “resistant to change.”

As the late Peter Scholtes said:

“People don't resist change, they resist being changed.”

When leaders or change agents complain that people are resisting change, do they really mean people are “being resistant to my idea?”

Dr. Deming, in his “system of profound knowledge,” talked about four key elements:

- Appreciation for a system

- Knowledge of variation

- Process Behavior Charts help with those first two, I'd add

- Theory of knowledge

- Psychology

Deming often gets labeled as a statistician, but he said that psychology was the most important thing for managers to understand.

Motivational Interviewing, Being Stuck, and Getting Past Ambivalence

In recent years, as I've blogged and podcasted about, I've taken an interest in a method for addiction counseling called “Motivational Interviewing” (and I've made a page with information and links to resources).

In a nutshell, traditional counseling shamed the addict and made them feel bad for being an addict. Counselors would often tell the patient what to do, and that would lead to pushback.

We see similar dynamics in the workplace.

“You need to do Gemba walks.”

“No, I don't,” is a natural reaction.

When we push an idea, others will push back. It's natural, and it should be expected.

“Motivational Interviewing” takes a very different approach. It's more effective in counseling settings, and I can see where it would be more effective in the workplace. In fact, Motivational Interviewing is something that's been taught and used within Toyota (see Ron Oslin's webinar about this).

Motivational Interviewing is defined in the seminal book on the approach:

“… a person-centered conversation style for addressing the common problem of ambivalence about change.”

In this fantastic book about Motivational Interviewing for Leadership, the authors say:

Resistance is “… a term that seems to treat a normal part of the change process as abnormal or pathological… without recognizing how we, as leaders, may be contributing to the issue.”

Here my podcast with those authors here, if you like.

Resistance to change isn't a problem. It's an expected part of the change process. And that's a key… change is a process. Change isn't like flipping a light switch. It takes time, effort, conversation… and that's why Motivational Interviewing is helpful in the workplace when we're leading people.

Instead of labeling somebody as bad for resisting change and giving up on them, we should “lean in,” as they say. Detecting resistance is the start of the conversation, not the end of it.

A less-loaded term that's used in the M.I. methodology is “ambivalence.” Somebody who is ambivalent about change is on “both sides of the fence.”

Recently, I was talking with a nursing unit manager who was struggling to find time for daily huddles and Gemba walks.

She said, “I'm stuck.”

That's classic ambivalence language. Instead of making her feel bad or telling her what to do, my role as a coach is to engage her in conversation about change.

Somebody who is ambivalent will say things that we'd call “change talk.” The nursing manager said, “I need to do those Gemba walks each day.”

She knows what she needs to do, but there are also reasons NOT to do it, as we'd hear in what's called “sustain talk.” She said, “It's really hard to make time.”

Me doubling down and telling her she should do Gemba walks or that she needs to doesn't give her any new information. She has some level of commitment and knowledge of what she needs to do. But, it's not happening. The predictor of change, in the M.I. mindset, is when change talk outweighs sustain talk.

I've had my own struggles with ambivalence around Measures of Success. Here's a situation where the change (writing a book) is completely self-initiated. There are many benefits that I predict would come from writing this book. But, even positive change can be difficult.

My change talk about the book, over time, has included things like:

- I need to write it

- I'm going to write it

- I want to finish it

- I'm going to finish it

My sustain talk, in my own head, included things like:

- I'm busy

- What if people don't like it?

- What if it doesn't make a difference?

How do coaches help somebody get past ambivalence? Telling them what to do, or what M.I. calls “the righting reflex” is human nature, just as resistance to change is natural and expected.

The book Motivational Interviewing describes the righting reflex as:

“… the desire to fix what seems wrong with people and to set them promptly on a better course, relying in particular on directing.”

It's human nature to tell people what to do.

It's well-intended.

The problem is… it doesn't work.

Last summer, I saw a fantastic presentation at the Lean Coaching Summit with leaders from a non-profit called “Beyond Emancipation.”

One of the women said:

“I spent eight years telling foster kids what to do… and it was exhausting.”

We can't blame them for telling kids (or young adults) what to do. It's human nature. It's well intended.

But they eventually learned (without Motivational Interviewing being the direct influence) that:

“We believe that the person closest to the problem is closest to the solution.”

That reminds me of the spirit of Motivational Interviewing. And, it reminds me of Lean leadership.

We don't tell people what to do. We don't leave people alone to figure it out themselves, either. We guide, coach, and mentor them.

Evoking reasons for change… guiding people through that change process is more effective.

So to do that, the four Motivational Interviewing processes are:

- Engaging

- Focusing

- Evoking

- Planning

We can guide people through this, but only if they've given permission to be coached. We can't assume somebody wants to be coached. If we make that assumption, they maybe won't accept it. If we rush to the planning phase without first engaging the person and building a relationship, change is less likely to happen.

The guiding and coaching involves skills that can be remembered with the OARS acronym:

- Open-ended questions

- Affirmations

- Reflective Listening

- Summaries

In Lean, people often emphasize leading by asking open-ended questions. But, as you learn more about M.I., you'll see that statements can be helpful at times.

When we face somebody who is stuck, like that nursing unit manager, we can ask questions like:

- Why would you want to make this change?

- How might you go about it, in order to succeed?

- What are the three best reasons to do it?

I asked her to articulate WHY it's important to do Gemba walks. That evoked change talk that led her in a more positive direction. I asked these questions of myself related to my book, as well.

Through coaching, we can help the person articulate more change talk, aiming to help them increase their level of commitment and to also increase their confidence that they can make the change happen.

Let's Reframe Resistance to Change?

I think it's important for leaders and change agents to reframe “resistance to change.”

In the past, we might have asked, “Why are they resistant to Gemba walks?” or “Why are they being resistant to Process Behavior Charts?”

Going forward, let's try to engage people in a conversation about change. That's more difficult and more time consuming than labeling people and casting them aside. But, it's more effective.

What's more important – being right or being effective?

I can't tell you to try that approach. I can only invite you to learn more about it.

Soft Launch of Measures of Success

Today, in conjunction with the conference, I'm doing a very, very soft launch of Measures of Success through LeanPub.com.

EDIT: The book is now available in multiple channels. Learn more through the book's website.

I'm still working with potential cover concepts, such as these and others that I'll have made:

I've released the first three chapters of the book in the iterative “Lean Publishing” style that encourages authors to “publish early and publish often.”

If you buy the book now as an early adopter, you'll have the chance to give me feedback, and you'll get notified as more content is added to the book.

Today, you'll be able to download a PDF file, along with MOBI (Kindle) and EPUB formats.

When the book is done (my goal is June — there's change talk, in the form of commitment), it will also be available through the Amazon Kindle store and perhaps also as a paperback book.

EDIT: I got the book done by August :-) The paperback version should be available by March 2019.

Please scroll down (or click) to post a comment. Connect with me on LinkedIn.

Let’s work together to build a culture of continuous improvement and psychological safety. If you're a leader looking to create lasting change—not just projects—I help organizations:

- Engage people at all levels in sustainable improvement

- Shift from fear of mistakes to learning from them

- Apply Lean thinking in practical, people-centered ways

Interested in coaching or a keynote talk? Let’s start a conversation.

Engaging people in conversations about change is a great start. Additional information may be needed to fully unravel the problem(s) because there is much that conversation does not reveal. The further up the hierarchy you go, the more important the additional information becomes – and it does not usually come voluntarily. It must be deduced through observation and by deconstructing language, symbols, decisions, actions, etc. This is especially true given that people at lower levels tend to mirror the thinking, behaviors, and decisions of their leaders.

Red/Green column charts with a target line are another method used in LDM. Out of curiosity other than Deming’s teachings how would you recommend someone connect process behavioral charts and MI in real world application? Worded differently how can I integrate MI and process behavioral charts? After all they were presented together, I just figured there’s a connection?

As I wrote about in “Measures of Success,” I think we can use lessons from Motivational Interviewing to think about helping others adopt Process Behavior Charts. We can’t force people to change. We can invite them to learn. What’s their motivation for changing? For trying a new way? The conversation can start there perhaps.