Joining me for Episode #344 is David Reid, a mechanical engineer whose career has taken him from improvement work at Michelin Tire, to being a pastor, to now helping the Chick-fil-A restaurant chain improve through Lean and Kaizen practices and mindsets.

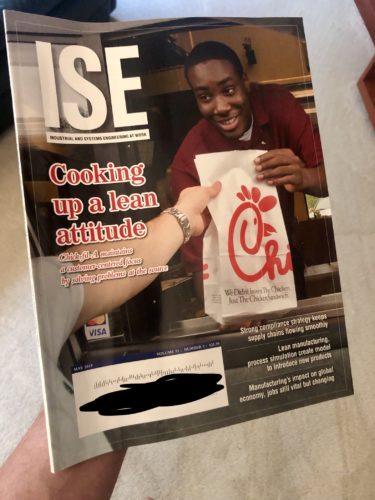

I was really excited to see the cover story that was in the May 2019 issue of ISE Magazine (Industrial & Systems Engineering). The headline inside reads, “From lean modules to a lean mindset — Chick-fil-A's success shows how leveraging your greatest asset speeds up cultural change.”

In this episode, I get to ask David about some of the drivers for Lean at Chick-fil-A, which is already a high-growth company with many happy customers and employees.

How do they influence the owner/operators of stores to embrace Lean and to engage every employee in continuous improvement? Why did they learn that a top-down engineering-driven model couldn't possibly drive enough improvement? How does a Facebook page enter the equation for employees (and note that using Facebook was an employee idea) instead of “building an app.”

There are many great “nuggets” of wisdom here from David, pun absolutely intended. I hope you enjoy the episode!

Streaming Player:

For a link to this episode, refer people to www.leanblog.org/344.

For earlier episodes of my podcast, visit the main Podcast page, which includes information on how to subscribe via RSS, through Android apps, or via Apple Podcasts. You can also subscribe and listen via Stitcher or Spotify.

New! Subscribe and listen with Spotify:

Key Quotes:

“We realized a top-down, engineer-driven model could never drive enough improvement. Every team member has to be a Lean thinker.”

“Each Chick-fil-A restaurant is really a $6 million manufacturing plant–with perishable products and variable demand.”

“One of the eight wastes is underutilizing people's creativity. We'd be crazy not to unleash 150,000 team members to improve their own work.”

“I'd much rather have to restrain mustangs than kick mules.”

“Our operators and team members give us our incredible reputation. Lean just helps them solve the problems that bother them.”

Questions, Topics, and Links:

- David's LinkedIn page

- IISE article: “From lean modules to a lean mindset — Chick-fil-A's success shows how leveraging your greatest asset speeds up cultural change” — IISE members only

- Before we talk about Lean at Chick-fil-A, can you first introduce yourself and your career as an engineer and a Lean practitioner? Where did you get started?

- How did you end up at Chick-fil-A?

- What's the need or opportunity for Lean at CFA?

- African proverb: “Every morning in Africa, a gazelle wakes up, it knows it must outrun the fastest lion or it will be killed. Every morning in Africa, a lion wakes up. It knows it must run faster than the slowest gazelle, or it will starve. It doesn't matter whether you're the lion or a gazelle-when the sun comes up, you'd better be running.”

- Why is it important to engage EVERY employee as a lean thinker and practitioner? Can you talk about that evolution from a top-down, engineer-driven approach?

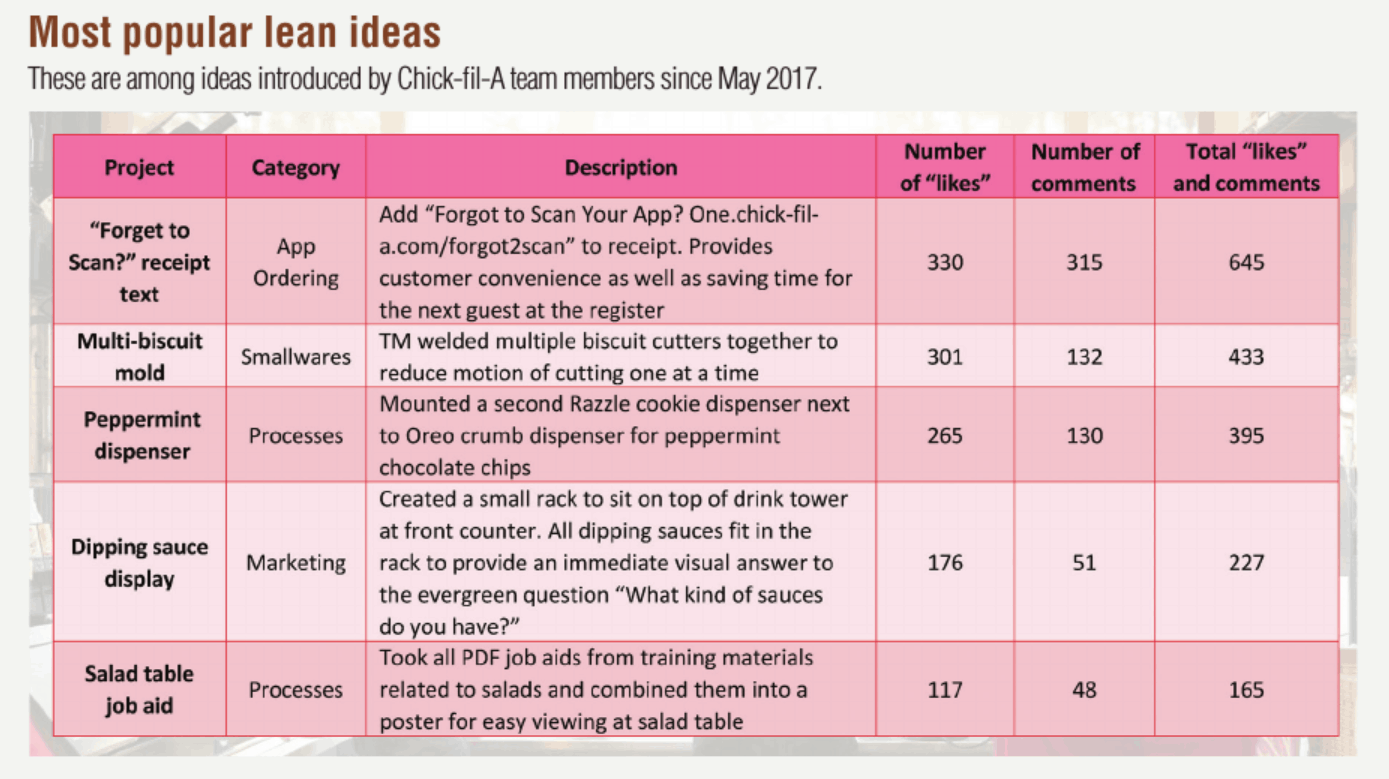

- Examples of employee-driven improvements?

- “Forgot to scan?” message on receipts

- Biscuit roller cutter

- Sauce display for customers

- How can you influence the owner/operators to utilize Lean and to engage people? Pull?

- Why is it important to have “sandbox boundaries” and what are those? What would be out of bounds? What happens if there's an idea that can't be implemented for some reason?

- “I'd much rather have to restrain mustangs than to kick mules” ?

- I know the drive-throughs are fast… 300 cars per hour PER LANE? That's a takt time of 12 seconds… How? :-)

- How do you spread and share ideas across so many locations??

- Lean Facebook site

- Why is it important to celebrate wins?

From the IISE article:

Transcript:

Introduction

Announcer: Welcome to the Lean Blog podcast. Visit our website www.leanblog.org. Now, here's your host, Mark Graban.

Mark Graban: Hi, this is Mark Graban. Welcome to episode 344 of the podcast. Joining me today is David B. Reid. He's a mechanical engineer whose career has taken him from doing improvement work at Michelin Tire, to being a pastor for over a decade, and now he's helping lead the Chick-fil-A restaurant chain through lean and kaizen practices.

I was really excited to see the cover story in the May 2019 issue of ISE Magazine. The headline inside read, “From Lean modules to a Lean Mindset, Chick-fil-A's success shows how leveraging your greatest assets speeds up cultural change.” And of course, that greatest asset is their employees.

In the episode, David describes each of their 2,000+ stores as a little food manufacturing facility–about a $6 million plant. Today I get to ask David about the drivers for Lean at Chick-fil-A, which is already a high-growth company with many happy customers. How do they influence owner-operators to engage every employee in continuous improvement? Why did they learn that a top-down, engineering-driven model couldn't possibly drive enough improvement? How does a Facebook page, an employee's idea, enter the equation instead of building an app?

There are many great nuggets of wisdom in here from David, pun absolutely intended. I think you'll really enjoy it.

Again, we are joined today by David Reid. David, thank you for joining us. How are you?

David Reid: Mark, thanks for having me. I'm really glad to be here.

David's Career Journey

Mark Graban: I loved your article. Before we talk about lean at Chick-fil-A, could you introduce yourself and talk a little bit about your career? Everyone's got an interesting path. What's yours?

David Reid: I'm a mechanical engineer from Georgia Tech. My senior design project was really interesting. My professor would put us in groups of three or four and pose a money-saving problem for a big hotel in Atlanta, the Westin Peachtree Plaza. He would frame it in engineering terms, like, “On the coldest day of the year, how should the Peachtree Plaza heat the building?”

He would lecture for two weeks on the physical principles involved, and we would look at utility rates and other factors. Then, we'd write a 10-page paper on the most economical way to heat the building. The interesting part was that he would read all the papers, pick the best one, give that group an A, and then go sell that solution to the Westin. I really loved that idea of using engineering principles to solve real-world business problems.

When I interviewed with Michelin Tire Company after college, I was passionate about that example. Michelin said, “Well, that's what industrial engineers at Michelin do,” and I decided that's what I wanted to do. I worked there for five years, tightening up standards and learning about systems and processes.

I didn't call it “Lean” at that point; we talked a lot about just-in-time production. As a side note, I left Michelin, went to seminary, and pastored a church for 10 years. When I went back into engineering, I kept hearing everyone talking about Lean. I took some refresher courses and realized a lot of it was the same industrial engineering principles. I recognized that Toyota had done a great job applying principles to reduce waste and satisfy the customer in such an elegant way.

From that point on, I was sold on it. At this point, I Kanban things we buy for groceries at home and 5S everything so I can find my keys. My first thought for any problem is, “What's the Lean approach to fixing this?”

Mark Graban: So how did you end up at Chick-fil-A?

David Reid: After 10 years of church planting, my family and I needed a break. I was looking to come back to engineering and got a headhunter call looking for a Michelin industrial engineer to work at Chick-fil-A. My boss there was a Michelin IE 25 years ago, and he liked their systematic approach to continuous improvement.

My first thought about Chick-fil-A was when the headhunter said they were analyzing their oven capacity. I love capacity modeling, but for some reason, “oven capacity” just didn't sound sexy. My wife said, “Well, what's so sexy about tires and concrete?”–two other industries I've been in.

The neat thing is, as I began to work with Chick-fil-A, I found out it's really 2,000 six-million-dollar manufacturing plants. They each have different product mixes and make a perishable product with variable demand. I always joke to my engineers, “When I made tires, you could make a thousand tires an hour at two o'clock in the morning. With chicken sandwiches, you can only make a lot of them between 11 and one.” It has an amazing number of Lean applications.

Mark Graban: You mentioned oven capacity. They're not baking their own buns at the store, are they?

David Reid: Great question. Not buns, but biscuits. For breakfast, we actually hand-roll our dough and make fresh, handmade biscuits every day.

The Case for Lean at Chick-fil-A

Mark Graban: I'm really curious. Chick-fil-A has been, by all measures, a really successful business. The product is delicious, and the service is speedy yet exceedingly courteous. It doesn't seem like Chick-fil-A needs to improve much, but what's the compelling need for Lean?

David Reid: Thank you for the kind comments. It's really our operators and team members around the country that give us that incredible reputation.

Here's the best way I can think of it. You may have heard the African proverb: Every morning in Africa, a gazelle wakes up knowing it must outrun the fastest lion or it will be killed. Every morning, a lion wakes up knowing it must run faster than the slowest gazelle, or it will starve. The moral is, no matter whether you're a lion or a gazelle, when the sun comes up, you'd better be running.

For Chick-fil-A, we have had amazing growth. Over the last five years, we've doubled from $5.5 billion to $10.6 billion in sales. We're experiencing Jim Collins' flywheel effect, where a lot of people have been pushing on the right things for a long, long time. But we want to stay there. Our goal is to satisfy our customers. “Second-mile service” is one of our core values. We want to be the most food-safe place in America that provides the fastest service.

With all these dreams, there are lots of challenges to be solved. As we grow, we run the risk of slowing down our service because there are so many people ahead of you who want Chick-fil-A. That's our mantra right now: How do we keep providing convenience and speed, even as we're doing bigger volumes?

Lean in Practice: Drive-Thru Improvements

Mark Graban: The IISE article mentioned something about 300 cars per hour in the drive-thru. Is that a goal? Is that per lane? Can you talk about that challenge and how the drive-thru lanes are improved?

David Reid: That's a great question. If you think about it, the drive-thru is a manufacturing process. A customer is hungry, decides to eat with us, gets in our line, decides what they want, communicates the order, and then a transaction happens. That kicks off a manufacturing process in the kitchen to cook the food. Then there's the delivery and handoff. You have the food production and order-taking meeting at the window.

To decrease that cycle time, you have to look at all those steps not as a serial process, but as multiple steps you could potentially do in parallel.

The original drive-thru was just a single window where you ordered and got your food. Then restaurants added an order box up ahead, which lets you take the order and start working on the food before the person gets to the front. We've taken that concept and pushed it out as far as we can. We're now doing things like walking up the lane with an iPad and taking your order way before you get to the window.

This allows us to start making your food quicker, and we can take your payment so it doesn't even happen at the window anymore. We've started designing our drive-throughs with an exit lane so you're not trapped. If we can walk upstream and give you your order, you can pull out. Theoretically, that car spends zero time at the window. 300 cars per hour is our theoretical maximum right now. It requires unlimited demand, and many of our restaurants, particularly in Texas, have constant lines of cars.

Mark Graban: So part of that is designing the lot so there's no curb preventing you from pulling out?

David Reid: Exactly. We also build a safety lane for team members to walk up and down. We have canopies that provide shade, air conditioning, and even heaters so our team can work outside comfortably. The one thing we try not to do is push you ahead and ask you to wait. If you've ever been told to “pull ahead” at a fast-food restaurant, it generally means they've crashed and you're the one holding them up. That's not a good feeling as a customer.

Lean from the Front Lines: Employee-Driven Ideas

Mark Graban: In the article, you talk about the transition from engineer-driven projects to engaging every employee as a lean thinker. Can you share a bit about that evolution?

David Reid: This has been a breakthrough for us. Most of us came from a background where you go to engineering school for four years, learn the ropes for a couple of years, and then you're qualified to come up with improvements. That's a really expensive way to do things. I have eight industrial engineers for $10 billion worth of sales across 2,200 locations. You can only deploy those expensive resources on the very top problems.

That leaves a ton of problems that anyone with a lean mindset could absolutely solve. One of the eight wastes is underutilizing your team members' creativity and skills. Why aren't we making them an army of lean thinkers to solve their own problems? We found that it's not costly–they're already doing the work. It's infinitely scalable, especially with a way to share ideas. And it's way faster than waiting for a paid engineer to work on it.

Mark Graban: Can you share some favorite examples of team-member-driven improvements?

David Reid: They come up with great ideas. For example, with our mobile app, people paying with cash would often forget to scan their app to get points. It was clogging up our system. A team member came up with the idea to use the customizable field on our receipts to print the website link for getting credit. They put “Forgot to scan? Go to this website.” at the bottom of every receipt. That idea was shared on our Lean Facebook site and immediately got 600 comments. We liked it so much we sent it out to the whole chain.

Another team member asked, “We make a lot of biscuits. Why do we only cookie-cut them out one at a time?” They welded six of our biscuit cutters together so they could press one time and get six biscuits. We had some food safety concerns about the weld, but we loved the idea. So, we took their concept and developed a plastic multi-biscuit roller. Now you just roll it out like a rolling pin, and it cuts the entire sheet of dough into biscuits.

One last one: a team member created a little rack to display all our sauce flavors right at the cash register. Customers can see all the options–Buffalo, Polynesian, Chick-fil-A sauce–while they're ordering and don't have to ask. It speeds up the transaction and shows care for the guest by anticipating their needs.

The Pull of Lean: Influencing Culture

Mark Graban: Because you have owner-operators running their own businesses, how do you influence them to utilize Lean and engage people when it's not a top-down model?

David Reid: We have a culture of satisfying the customer, so improving to do that better is table stakes. Our founder, Truett Cathy, was all about the customer. He chose operators who would take care of customers and hired staff who would take care of the operators. That culture is reinforced through training.

We present Lean as a way to help you solve the problems that bother you. We start with a felt need. We don't dictate to operators, “Hey, you need to shave off minutes here or save costs there.” We ask them, “Where is your felt need? What would you like to fix?” We want to come alongside them and provide tools to help.

At the team member level, the question we ask is, “What makes your job hard?” We let them follow their curiosity and their pain points and say, “Let's go after it and fix whatever's bothering you.”

Influence and Boundaries

Mark Graban: Can you elaborate on the idea of “sandbox boundaries”? You mentioned some around food safety, but what else is out of bounds?

David Reid: Some people hear that we let 150,000 team members–many of whom are 16 to 18–do lean improvements on food that goes out to 3 million people a day, and it can sound a little scary. We have a very healthy respect for our position, so we created a “sandbox” of improvements team members can work on.

There are four boundaries that team members and operators are not allowed to cross. They can't do anything that impacts:

- People Safety

- Food Safety

- Product Quality

- Equipment Warranty

If an idea affects one of those, we have the right and responsibility to say, “This has unintended consequences, and you're not allowed to do that.” For example, you can't cook the chicken for less time to be faster. That affects food safety. Product quality is another. A team member had a great idea to mix lemonade in a different order to save time, but it turned out the original order was important for dissolving the sugar properly to get our signature taste.

For equipment warranty, an idea went viral to turn the vent hood on our ice cream machines around to stop it from blowing napkins. But the machine was designed that way to vent hot air away from the motor. The manufacturer confirmed it would wear out the motor faster, so we had to issue a polite “cease and desist.”

Mark Graban: There's an expression you used in the article: “I'd much rather have to restrain mustangs than to kick mules.”

David Reid: That's right. If you say, “Hey guys, we want ideas from you,” but then you punish people when they come up with an idea, you're going to shut down innovation. We believe that one of the eight wastes is our own team members' creativity. We have 150,000 eyes looking at our process every day. We would be crazy and extremely wasteful not to enlist that army of experts to improve the process.

Yes, there will be times when we have to say, “Whoa, let's not do that,” but there will be a thousand times more when they come up with something that is totally fine, and the company didn't have to spend a dime for that improvement to happen. We would much rather have all these people improving the process.

Sharing and Celebrating Wins

Mark Graban: I wanted to hear more about the Facebook page. How does that work?

David Reid: Most of this comes to light through our internal Facebook page. My answer to people who think letting team members innovate is risky is this: they're doing stuff anyway. At least with the Facebook page, a reward system, and a way to share ideas, I have some visibility into it.

When an operator is interested in Lean, they can request a one-day class. At the end of that day, they are invited to an internal Facebook page called the “Chick-fil-A Lean Initiative.” We ask them to keep the site pristine–every post should be a meaningful improvement.

Team members post a picture and a description of an improvement they made. It could be how they organized condiment shelves or a Kanban system they created. Other team members see it, like it, and tag people in their own restaurants. The more likes and comments a post has, it generally means it was a great idea.

They also self-police each other. If someone posts something that isn't food-safe or will void an equipment warranty, another operator will comment and say, “Hey, I don't think that's a good idea for this reason,” and they kind of police themselves.

Mark Graban: Why is it important to celebrate wins and participation? How do you balance recognition and rewards?

David Reid: We just want to celebrate good work. When the “forgot to scan” idea came up, our marketing team wrote an article about it to share with every restaurant and to celebrate the team member who came up with it. He probably didn't get any money, but he got recognition that the whole company thought his idea was great.

We've also run contests. We had an issue with the time it took to transition from dinner service to breakfast. We ran a contest for a month: “We want your best ideas on how to transition from dinner to breakfast. We'll give a $100 gift card to whoever gets the most likes.” It created a fun competition and generated a ton of ideas–how people Kanban their dishes, how they set up a cart for the morning, and more. For $100, we celebrated the winner and generated a wealth of ideas for us to sift through.

Conclusion

Mark Graban: Do you have any final comments for the listeners?

David Reid: I think Lean is a great toolset, and it's a shame if not everyone in your company is using it. We feel like we're building a valuable skillset in our team members for the future when we train them on Lean. The thing that's been most surprising to me is our “Lean Kickstart,” which is a one-day class. We teach team members about the eight wastes, 5S, and spaghetti diagrams. By the end of the day, they're equipped to go and start a project.

We have seen so many complete culture changes in restaurants from people looking to reduce waste. I think it's going to get bigger and bigger over time and become a competitive differentiator for us. When you have a whole team of frontline workers thinking about the process through the eyes of Lean, you're just going to leave everybody else in the dust.

Mark Graban: Great advice. David Reid, thank you again so much for your time. Really great talking to you.

David Reid: My pleasure, Mark. Thank you so much for having me. They did give me the article to post on my LinkedIn, so you can see it there: David B. Reid, R-E-I-D.

Mark Graban: Oh, great. I will definitely link to that in the show notes. Thank you for mentioning that, and thanks again for being the guest.

David Reid: Thanks, Mark. It's been great.

Please scroll down (or click) to post a comment. Connect with me on LinkedIn.

Let’s build a culture of continuous improvement and psychological safety—together. If you're a leader aiming for lasting change (not just more projects), I help organizations:

- Engage people at all levels in sustainable improvement

- Shift from fear of mistakes to learning from them

- Apply Lean thinking in practical, people-centered ways

Interested in coaching or a keynote talk? Let’s talk.

Join me for a Lean Healthcare Accelerator Trip to Japan! Learn More

Mark – Great guest and podcast. I liked the observation that a form of waste may be identified, but that step or process is of value to the customer, it is not waste.

Great interview Mark. As an Atlanta native, a full-fledged Chick-Fli-A fan, and a full-time lean practitioner, I loved having my worlds collide in your interview.

Those of us who make our living doing process improvement know that none of the wonderful things David spoke about would happen, without an incredibly strong culture of servant-leadership. I’ve been to many CFA’s across the country and seen leaders doing what ever it takes to serve their customers. As I understand their system, CFA franchisees (operators) have to work in a store for at least 1-year, before they are “eligible” to spend a substantial amount of money to become franchisees. This one step ensures that future leaders “get” the corporate culture.

I heard a couple of wonderfully surprising things as well. Hearing that CFA corporate funds big changes to the restaurant / capital equipment is awesome. I was happily amazed to hear that field leaders can ask AND GET someone from corporate to come to them to teach lean principles. Wow! Both of these actions demonstrate far-sightedness and wonderful leadership in an era where companies have been working for decades to hammer out every expense that will not return hard-dollar benefits in the current quarter. (maybe a podcast on how this attitude is incompatible with lean’s “respect for people” tenant is in order?)

Adding Lean this wonderful culture will surely result in CFA becoming the world’s largest and most loved place for fast good food in the very near future!

Thanks again Mark!

Thanks, Bob. Glad you enjoyed it!

Comments are closed.