tl;dr: In the blog post, we delve into MLB's ongoing struggle with slow and lengthy games, analyzing recent rule changes aimed at reducing game time. Special focus is given to the newly enforced pitch clock for the 2023 season, its historical context, and its efficacy as tested in the Minor Leagues.

Did the new pitch-clock rules make a statistically meaningful difference in the MLB game length?

YES!

Here's the original post as written in April (and updated in October):

As I've blogged about before in recent years (here and here), Major League Baseball (MLB) has, as Toyota people say, a “big vague concern”:

Games are too long and too slow!

In recent years, they've tried a few countermeasures that have proved ineffective. Starting in 2017, an intentional walk no longer required four pitches to be lazily thrown outside of the strike zone — the batter is just told to proceed directly to first base. Pitching changes have been limited. The time between innings has been shortened.

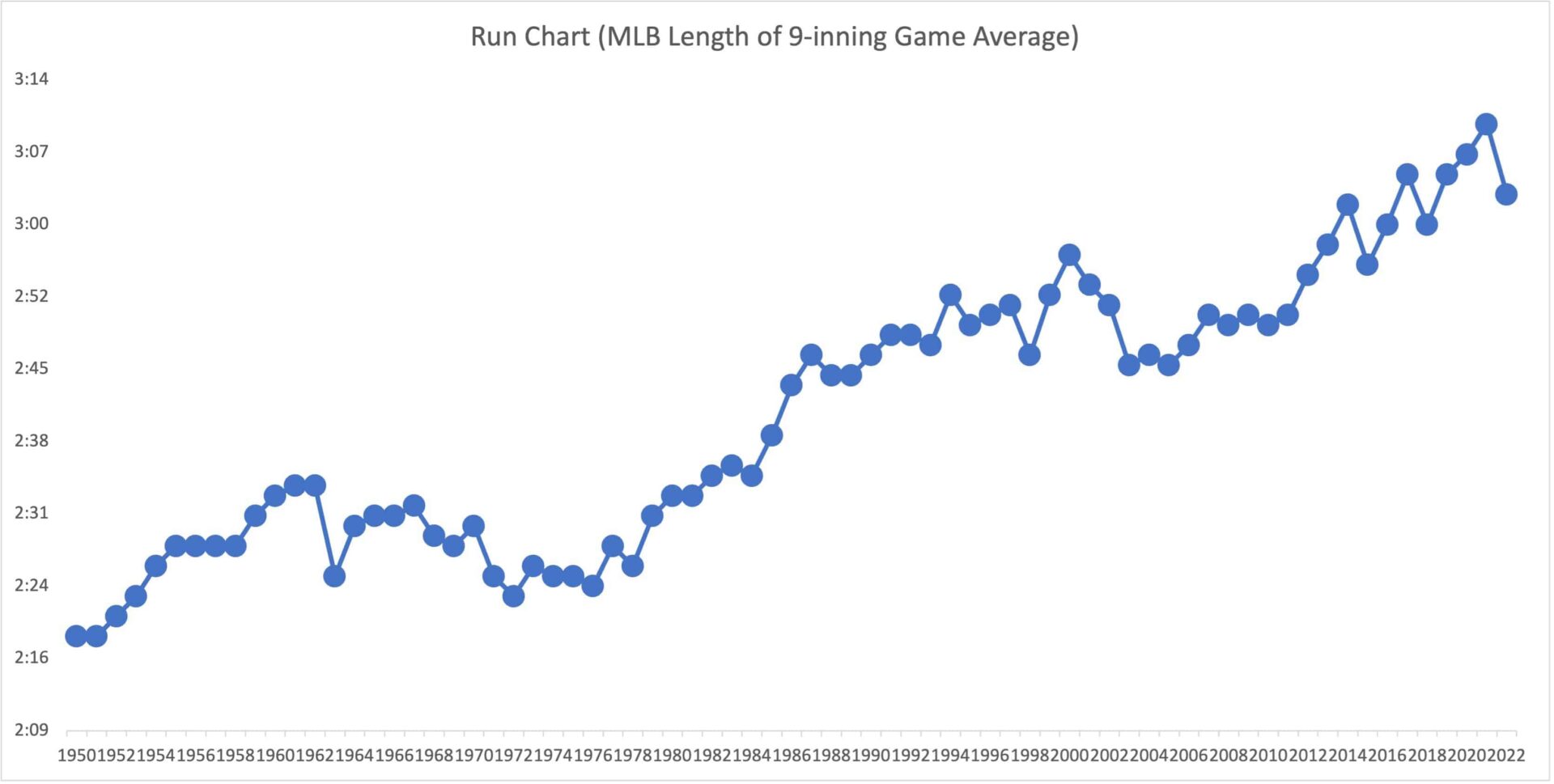

Last year, we saw many headlines or articles with facts, including the average length of a game and a comparison to the year before. Those numbers are true, but not super helpful — as we often see not just in the news but in workplaces.

- The average length of a 9-inning (no extra innings) MLB game in 2022 was 3:03

- That was eight minutes shorter than in 2021

As the statistician Don Wheeler says, “No data have meaning apart from their context.” Three hours and three minutes is true, but it's missing context. Does the decline of eight minutes mean that rule changes were working? Was there a statistically meaningful effect?

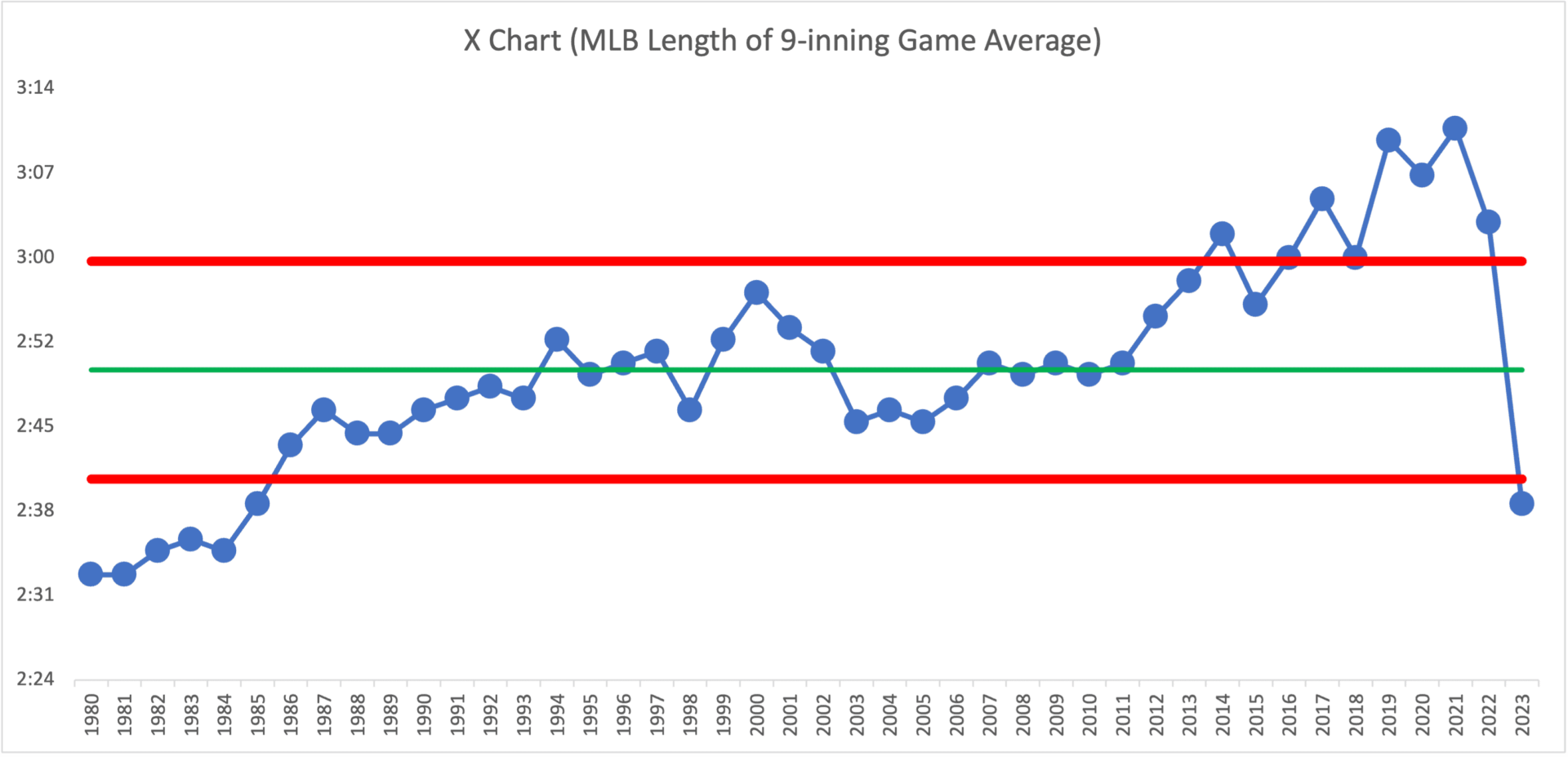

A run chart going back to 1950 tells us much more (updated through the 2022 season). Note the Y-axis, as it doesn't go down to zero.

There's certainly a dip downward in 2022. But there were other years recently where the number went down. We shouldn't overreact to every data point.

Maybe it's fluctuating around what appears to be a linearly increasing average? Note that I just drew that red line; it's not a calculated linear trendline.

There will always be variation in a metric over time when it's fluctuating in a statistically-predictable range (referred to as “common cause” variation) — and those rule changes weren't having too much of an effect. Without additional rule changes, would the game times continue increasing based on player behavior and other factors?

The big vague concern was… still pretty big. At an average time of three hours, that's still deemed too long by MLB executives.

A Bold Countermeasure

For the 2023 season, MLB announced new rules, including the intent to strictly enforce a pitch clock to keep pitchers and batters from stalling and delaying the game. It's a 15-second pitch clock with nobody on base and 20 seconds with runner(s) on.

- The pitcher must begin his motion to deliver the pitch before the expiration of the pitch timer.

- Pitchers who violate the timer are charged with an automatic ball. Batters who violate the timer are charged with an automatic strike.

- Batters must be in the box and alert to the pitcher by the 8-second mark or else be charged with an automatic strike.

- Pitchers are limited to two disengagements (pickoff attempts or step-offs) per plate appearance.

- If a third pickoff attempt is made, the runner automatically advances one base if the pickoff attempt is not successful.

As with many good standards, there's room for judgment: “Umpires may provide extra time if warranted by special circumstances.”

Why make the big change now? Per a WSJ article:

“The problem had to become worse before people agreed that action was necessary,” Sword said.

That makes me wonder how bad the patient safety problem must become be before we take bold action? But I digress.

This ESPN Daily podcast with MLB writer Jeff Passan was an interesting dive into some of the history of the pitch clock, and I'll share some notes below.

Needing a New Standard or Enforcing the Old One?

Passan pointed out, as this 2021 article also does, that MLB had an existing rule (8.04) about the pace of play that was NOT being enforced.

“When the bases are unoccupied, the pitcher shall deliver the ball to the batter within 12 seconds after he receives the ball. Each time the pitcher delays the game by violating this rule, the umpire shall call ‘Ball.'”

Passan said that, back in the 1960s, famed owner Charlie Finley of the then-Kansas City Athletics installed a large pitch clock at his stadium (read more here). Passan says that umpires didn't like being shown up that way and, supposedly, only called violations against Finley's pitchers. The clock was then removed.

In 2015, MLB started fining batters $500 for stepping out of the box too often, but that's like fining you or me a quarter for some workplace offense. Players didn't care and the fines didn't last.

Experimenting in the Minor Leagues

MLB has smartly used a strategy of using Minor League Baseball as a testing ground for various rule changes. They can test their hypotheses on a small scale (in one league) and in settings where the risk is lower. They could test cause-and-effect relationships in real game.

Hypothesis or assumption: The pitch clock will shorten games

OK, sounds reasonable, but by how much? They could try to estimate it based on the recordings of old games, but it's better to try it out in real use.

I blogged about seeing a pitch clock at a Daytona Beach Tortugas game in 2017:

Passan said the minor league clock rule had a weakness in that limits on the pitcher stepping off the rubber weren't being enforced — a loophole that allowed a pitcher to reset the clock. So like MLB rule 8.04, a standard that's not enforced doesn't have much effect.

Passan used a tech term — A/B testing — to describe how experiments were structured in various minor leagues. They learned that the pitch clock, of all of the various rules, had the largest effect: shortening games by 20 minutes on average.

In 2021, as Passan described, a small group of MLB executives (including a former player) went to see what the pitch clock did to games by traveling to watch a game in Rancho Cucamonga. You could say they “went to the gemba.”

“OMG, this might actually work” was said to be the reaction. That was the day when the people in charge realized the game would include a pitch clock.

The WSJ reports it took all of one inning for them to reach that conclusion:

“Within an inning, we all kind of looked at each other and said we'd seen enough,” recalled Morgan Sword, MLB's executive vice president of baseball operations. They told each other: “We need this in the big leagues.”

Being Adaptable to Cutting the Fat

Passan said that fans aren't getting less baseball (the way you would by shortening games to seven innings). They are reducing some of the “fat” (the wasted time between pitches) — and he compared the rule change to liposuction.

With the rule being used for Spring Training 2023 (and now into the regular season), Passan said players aren't complaining to the union. This rule change was collectively bargained, by the way. From the WSJ:

The league made the rule changes a priority going into the contentious collective bargaining agreement with the MLB Players Association during the 2021-22 offseason. The relationship between the league and its players was in a tough place, in part because the players felt that MLB had little concern with their everyday expertise as they proposed and implemented changes to the game.

It's always sad when frontline personnel don't think executives care about them — in manufacturing, hospitals, or anywhere. NBA players have accused executives about not getting their input on important things like the ball they use.

MLB is involving players without turning into a democracy (and most workplaces don't try to be “democratic” in how they're managed):

The players know they can provide feedback and guidance in these discussions, but ultimately, if MLB wants to make a change, the league has the votes to do it.

Back to baseball, Passan also said that older fans (the “traditionalists” ) — the ones you might expect to resist changes — actually like the faster pace of play because that's how they remember it from the 1960s, '70s, or '80s. The younger fans are the ones who find the changes jarring… not that MLB has that many younger fans. The declining interest in baseball amongst younger Americans is often cited as one reason why the game needs to be sped up.

A Broader Test of Change and Learning

The pitch clock was used throughout Minor League Baseball in 2022. As Passan said,

“Once you have your hypothesis in place, what you need is data.”

The average game length was reduced by 25 minutes in 2022 (I think they had closed the loophole about stepping off the rubber). The minor leagues had tested a pitch clock with 14- and 19-second limits, but MLB went with 15 and 20 seconds (again, with bases empty or not).

We'd probably expect the same level of game time reduction in MLB, even with that tiny difference in the clock setting.

One benefit of testing this in the minors was to see if other loopholes would be found (from the WSJ):

The league knows that players will look for ways to manipulate them for a competitive advantage, and testing the rules in the minor leagues was a way for Sword's department to figure out where their ideas could be exploited.

Passan said players were very adaptable and that the number of violations went down pretty quickly.

We'll come back to the data in a bit.

How is This Seen on TV? Some Quick Iteration

This rule change requires changes to how the game is presented on TV. The NBA would have needed a similar adjustment when the shot clock was introduced in 1954. I don't know how many games were televised then, but it wouldn't have been an issue since the now-ubiquitous “score bug, the thing that constantly shows the score and time for games, wasn't unveiled until the 1990s. Now, we take it for granted that we'll see the clock on the screen constantly, along with the score.

But baseball had been the only sport without a clock, and many were proud of that.

I watched a few televised spring training games where a digital pitch clock (like an NBA shot clock or a football play clock) was visible beyond home plate (off to the side).

Passan expected that baseball “score bugs” would adapt to include this information. This rule change was announced in September 2022, so broadcasters of games had time to adjust.

I watched the Cincinnati Reds opening day game on TV and was surprised to see no pitch clock on screen to start the game (I didn't get a photo of that).

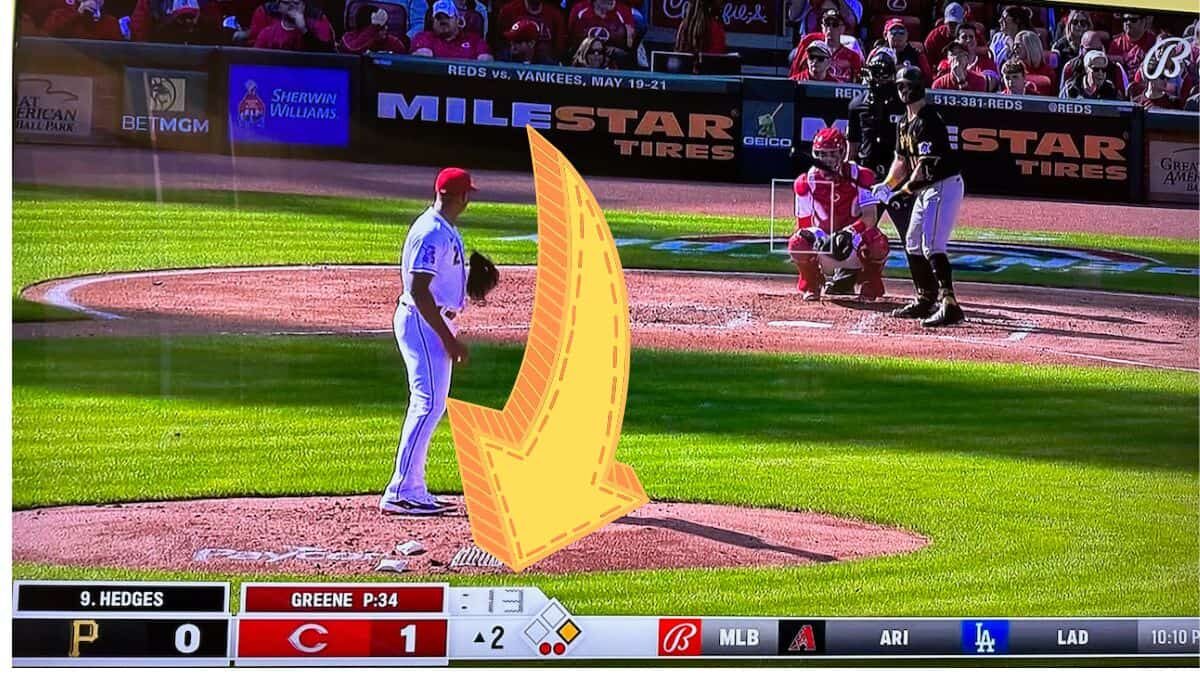

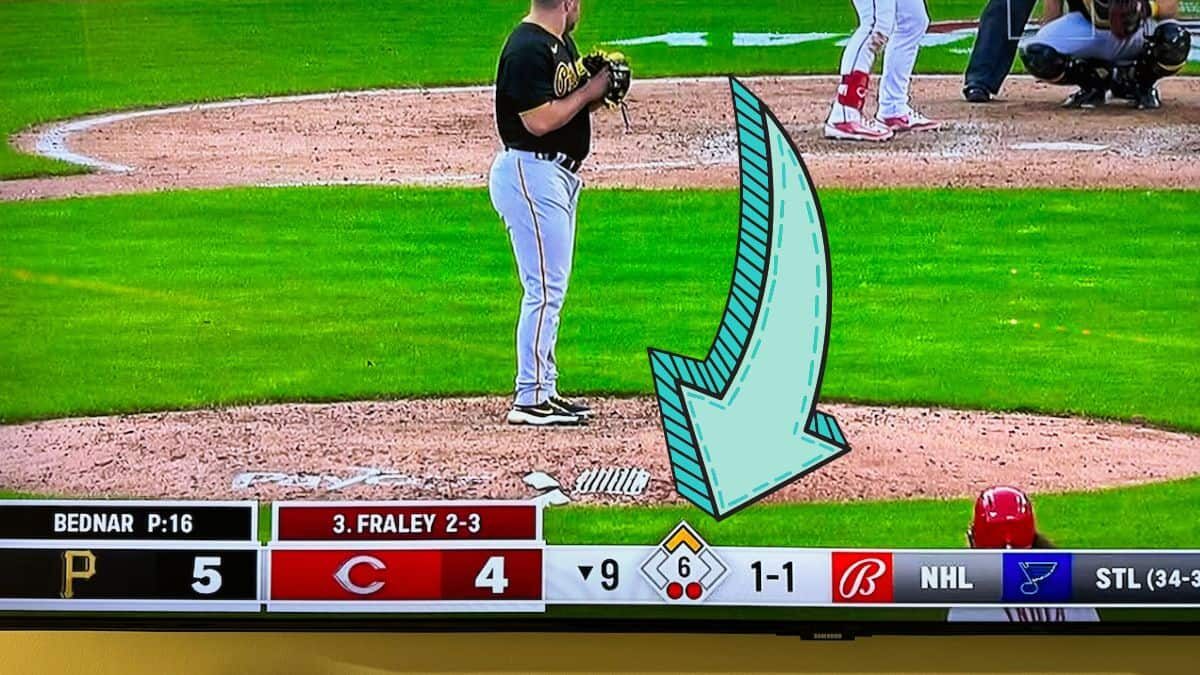

By the 2nd inning, a pitch clock was integrated into the graphic, even if it wasn't really elegant:

Sometime later in the game (I didn't catch exactly when), the pitch count had been integrated into the score graphics, being placed in the middle of the bases — and that part of the graphic had changed, as well.

Was this a lack of planning on the part of Bally Sports? If so, that's disappointing. But the quick iteration was even more surprising to me.

So, What's the Impact?

On opening day, the average game length was 2:45, down from an average of 3:12 on opening day of 2022. The two-data-point comparison approach that we often see in the media (and workplaces) isn't super helpful.

There is, of course, variation — game lengths ranged from 2:14 to 3:38 on opening day 2023.

I'll give the New York Times credit for using a run chart in their article.

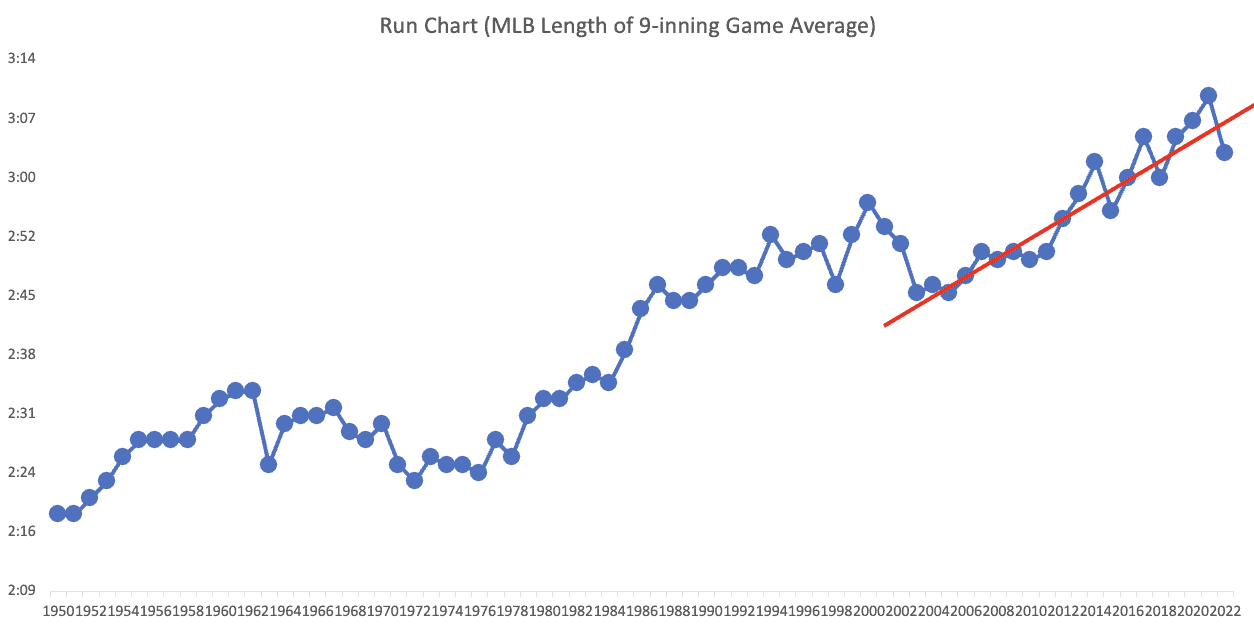

Through the first 35 games played this season, the average 9-inning game length is 2:41. That's down 22 minutes from 2022 and about what would have been predicted or expected based on the testing in the minor leagues last year.

Update April 7: For the first week of the season, through 97 games, the average game time is just 2:38 (and it's 2:36 per 9 innings)

Update: About one-sixth of the way into the season, April 30, the average game length is 2:36.

End of the regular season update: The find average game length per nine innings was 2:39 and the overall average game length was 2:42. The first part of the season was pretty representative of the season as a whole.

Here's a chart I made, trying to force the Process Behavior Chart method to it. The chart clearly shows that the game length was not fluctuating around a stable average. But viewing it as a simple run chart would have the same clear visual effect. The chart is updated to the final regular season 2023 number.

Instead of just tinkering around the edges with small rule changes (that had a small effect, if any) — MLB went big. Their big countermeasure is making a BIG difference.

Now, fans and experts can debate of MLB is solving a problem that really needed to be solved. People can disagree about that. But you can't disagree that the pitch clock has a huge impact. It's statistically meaningful — whether it's good or not is a judgment call that's in the eye of the beholder.

What About Side Effects?

Any countermeasure that “solves” a problem (or reduces a performance gap) might cause some side effect.

One spring training game ended when an umpire called an automatic strike on a batter for not being ready. Passan said that it was helpful that it happened early in Spring Training, as it served as a wakeup call to players and teams — this rule was going to be consistently enforced.

Passan wondered what might happen if a playoff game or a World Series game ends on a violation — causing a balk or walk (advantage to the batting team) or a strikeout (advantage to the pitching team).

He wondered if the rule should be enforced in the 9th inning of a game to avoid that, but then said that baseball's not the type of sport that likes to have different rules for different situations. We will see! Depending on how it plays out, it will be an experiment sure to bring intrigue (and possible outrage). Players have an entire regular season to adjust…

Positive Health and Safety Benefits?

This WSJ article says there will be other benefits (free link):

Baseball's Pitch Clock Has a Hidden Benefit for Players: More Rest

Managers are hoping that shortened MLB games this season will lead to less mental and physical fatigue for their top players.

Again, this illustrates the benefits of testing changes as part of PDSA cycles:

“We talked to minor-league players and coaches about the impact of shortened games,” said Morgan Sword, MLB's executive vice president of baseball operations. “We thought early that forcing a quicker pace was going to be negative for arm injuries. If anything, injuries were down a little bit in the minor leagues. At the MLB level, there are a lot of clubs that are big believers in the rest and sleep benefits of getting home a half-hour earlier every single night.”

More articles (free reading links when possible):

MLB Took a Slow Route to Developing a Speedier Game (free WSJ)

See How Baseball's New Rules Changed the Game (free NYT)

MLB Opening Day game lengths: How long were games on average in 2023 vs. 2022 with pitch clock? (free)

What do you think? Please scroll down (or click) to post a comment. Or please share the post with your thoughts on LinkedIn – and follow me or connect with me there.

Did you like this post? Make sure you don't miss a post or podcast — Subscribe to get notified about posts via email daily or weekly.

Check out my latest book, The Mistakes That Make Us: Cultivating a Culture of Learning and Innovation: