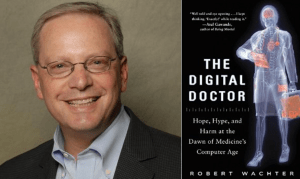

My guest for episode #220 is somebody I've wanted to interview for a long time, Dr. Robert Wachter, one of the leading voices in the modern patient safety movement. He's most recently author of a brand-new book The Digital Doctor: Hope, Hype, and Harm at the Dawn of Medicine's Computer Age. His book was excerpted in this New York Times Op-Ed piece, “Why Health Care Tech Is Still So Bad.”

Streaming Player:

In this episode, we cover topics including:

- How Bob got into the patient safety field

- Of all of the estimates of patient harm and death caused by medical errors, which does he find most valid?

- His perspectives on the interface between Lean principles and practices and the modern patient safety movement

- What were some of the pros and cons of the $30 billion in federal government incentives for EMR/EHR adoption?

- Is it fair to say that EHR systems solve some patient safety problems while solving others?

- Some of the new waste introduced by new “meaningful use” regulations

- The story of a preventable medication error that harmed a child – a combination of technology problems, human factors, and bad process

- Finding the balance between “system problems” and personal accountability (see this article)

Disclosure: I received an advance copy of The Digital Doctor from the publisher. I highly recommend the book for its balanced presentation of the promise, successes, and challenges of healthcare IT. The book discusses why electronic medical records haven't been adopted more quickly, why government incentives were introduced, and EMR/EHR systems are not the panacea that some had promised.

Previously, Dr. Wachter has written books on patient safety (that I've read and recommend) including Understanding Patient Safety and Internal Bleeding. He received one of the 2004 John M. Eisenberg Awards, the nation's top honor in patient safety and quality. He has been selected as one of the 50 most influential physician-executives in the U.S. by Modern Healthcare magazine for the past seven years, the only academic physician to achieve this distinction. I was honored when Dr. Wachter recently interviewed me about Lean and patient safety for his AHRQ “Web M&M” series.

Dr. Wachter is Professor and Associate Chairman of the Department of Medicine at the University of California, San Francisco, where he holds the Lynne and Marc Benioff Endowed Chair in Hospital Medicine. He is also Chief of the Division of Hospital Medicine, and Chief of the Medical Service at UCSF Medical Center. He has published 250 articles and 6 books in the fields of quality, safety, and health policy. He coined the term “hospitalist” in a 1996 New England Journal of Medicine article and is past-president of the Society of Hospital Medicine. He is generally considered the academic leader of the hospitalist movement, the fastest growing specialty in the history of modern medicine.

You can see his full bio here.

For a link to this episode, refer people to www.leanblog.org/220.

For earlier episodes of my podcast, visit the main Podcast page, which includes information on how to subscribe via RSS or via Apple Podcasts. You can also subscribe and listen via Stitcher.

Transcript:

Mark Graban: Hi, this is Mark Graban. Welcome to episode 220 of the podcast for March 30, 2015. My guest today is someone I've wanted to interview for a really long time. He's Dr. Robert Wachter, and he's one of the leading voices in the modern patient safety movement. He's most recently the author of a brand new book, The Digital Doctor: Hope, Hype, and Harm at the Dawn of Medicine's Computer Age.

In this episode, we're going to cover topics including how he got started in the patient safety field, what he thinks of the different estimates and studies about the scale of harm and death caused by medical errors. We're going to talk about his perspectives on Lean and patient safety, and we're also going to then dive into topics from his book, including the pros and cons, the good and the bad, of electronic medical records and electronic health records. What problems are they solving? What new problems are they creating? And at the end of the episode, he's going to share a story from the book about a preventable medication error that's a combination of bad systems, human factors problems, and bad process.

I really enjoyed the book. I really encourage you to read The Digital Doctor. He's also written previous books that I've read, including Understanding Patient Safety, which is now in the second edition, and the book Internal Bleeding. He's a professor and Associate Chairman of the Department of Medicine at the University of California, San Francisco. He's the chief of the Division of Hospital Medicine and chief of the medical service at UCSF Medical Center. Dr. Wachter actually coined the term “hospitalist” in a 1996 New England Journal of Medicine article. I didn't realize that about him until prepping for the interview, and he's the past president for the Society of Hospital Medicine, so I hope you'll enjoy the episode. If you'd like to see show notes and links to the book, or if you'd like to leave a comment, please go to leanblog.org/220. Hey Bob, thanks for being a guest. It's a real pleasure to have you here today.

Robert Wachter: It's a great pleasure to be here, Mark. Thanks.

Mark Graban: So, we're going to talk a lot about your upcoming book, The Digital Doctor, but I'm curious to hear first about your involvement in the patient safety movement. If you could introduce yourself and your background as a physician, and I think it would be great to hear about how you became a leader in patient safety.

Robert Wachter: Well, sure, I'd love to. My background kind of spools back to college when I was a political science major and for some reason knew I wanted to be a doctor, but was always interested in the way systems worked or didn't work and didn't understand that there were careers in medicine where you could combine those interests into something that was semi-coherent. So I always thought I'd become a doctor and I would kind of be interested in policy and politics on the side. After my training in internal medicine, I did a fellowship in health policy at Stanford, and started a faculty career and kind of moved from issue to issue. That seems to be my pattern, which is every five to seven years there's an issue that captivates me. It's an issue that has to seem really important to clinicians and patients, so pretty close to the ground, rather than insurance policy, for example, and has political and policy dimensions, usually involves money, which usually has some controversy associated with it. And those issues, I find I just enjoy trying to go in there and deeply understand them and articulate what's going on in a way that people find helpful.

The way patient safety happened was a little bit roundabout. In 1996, I had a new job running the medical service at an academic hospital in San Francisco. I had a boss who asked me to try to come up with some innovative way of organizing hospital care, and we started essentially the first academic hospitalist program. I wrote an article in the New England Journal in '96 that coined that term “hospitalist.” As the field grew over the course of its first few years–and since then, it's become the fastest growing specialty in history–I was worried a little bit about the field. And I was worried because we were being branded as being about saving money, and for a physician, I thought it was important to be about more than that, about making care better. My first fellow was a guy named Kaveh Shojania, who'd done a residency at the Brigham and arrived at UCSF in '99. I said, “What do you want to study?” And he said, “Patient safety.” And I said, “What's that?” And he said, “Well, you know, I was at Harvard, and there are these people there like Lucian Leape and Atul Gawande and David Bates, who are studying errors. And it's sort of getting to be an important and interesting and hot issue.” All of that came together. And then the IOM report, To Err Is Human, came out at about the same time and a bunch of light bulbs went off. And I said, “This is a really interesting, important issue.” And one I think that my approach, which is sort of being a generalist and diving in and trying to understand a lot of different facets of a multifaceted issue, might turn out to be valuable. And that's kind of how it all started.

Mark Graban: And here we are, of course, in 2015, and patient safety is still quite a large problem and a crisis of sorts. There are, I think, somewhat unknowable numbers and different estimates that started with that IOM report. And there's been more recent estimates about the number of Americans who die each year as a result of preventable medical errors. I'm curious, which of those estimates, which of those numbers do you feel like are at least most likely to be accurate or descriptive of the scope of this problem?

Robert Wachter: It's hard to know. I'm not sure. It obviously matters to the individual patients and families who are harmed and killed. At a policy level, whether it's a jumbo jet a day or three jumbo jets a day, it's sort of above a threshold that we should care about it and focus on it more than we have. I'd say the most credible numbers, unfortunately, are probably still the numbers that the IOM used, which came from a study that's now almost 25 or 30 years old, from the Harvard Medical Practice study, because that involved very, very detailed chart reviews of tens of thousands of patients and painstaking research methods. The more recent studies, where you sometimes see 2 or 300,000 numbers, the methods aren't quite as robust, but clearly it's a big number.

There's a little concern that the more recent numbers, which sometimes look worse and make it look like we're getting worse, involve new methods. And in some ways, as we look for harm, we find it. So my own sense is that we've gotten better, although certainly not better enough. In the areas that kind of discrete areas where we really do know how to measure, for example certain healthcare-associated infections, even medication errors, the evidence is pretty good that we have improved somewhat, certainly not enough. There are other areas of the patient safety field, the most prominent being diagnostic errors, where we have absolutely no idea how much harm there is because it's so hard to measure, but it's clearly substantial. We have clearly under-resourced and under-attended to this issue. I think that has gotten better in the last 10 or 15 years, but it's still not good enough. In part because as we get better, new hazards come our way. As we put in certain safety fixes, we learn that it's a little bit of “whack-a-mole” that yes, you fix one thing and another thing pops out the other end. So one prominent example, of course, is computerization, which I've gotten interested in recently. But another kind of interesting example is resident duty hours where we shorten the number of hours that residents work, which seems like a sensible thing to do. But what pops out the back end is we have far more handoffs. So now we have less fatigued people, but now we have to figure out how to do handoffs more effectively. And that's been a little bit of the story of the patient safety field. You take a step and a half forward and then one step backward and then try again.

Mark Graban: Yeah, and I agree that I like the way you said that. Well, we need to figure out how to do handoffs better because I think, you know, from the Lean perspective, we wouldn't accept the fact that, “Oh, you know, handoffs are done badly. Well, let's just… Okay, well then no, it's unsolvable.” Well, of course, you know, it's… that can be improved and we can break some of that maybe false choice between, you know, we can do longer shifts or we can do fewer handoffs. We can if we figure out how to do those better.

Robert Wachter: And I think that's what we're seeing. I can tell you at my own institution, when we shorten the duty hours for a year or two, it was pretty chaotic because, you know, we knew we had to have more handoffs, the math is quite obvious. And we sort of all of a sudden had all kinds of shifts changing and people picking up patients, but we really hadn't thought of this as a systematic problem. And now I look at the way we do handoffs and it's certainly far from perfect, but it is much, much more organized and there is a plan and people have thought deeply about how do we do it, what is the space, what is the timing, what's the protocol? And it's substantially better than it was a couple of years ago.

Mark Graban: Yeah. And back to the issue of things getting better in some instances. I mean, there are many success stories of hospitals, you know, reducing central line-associated bloodstream infection rates by 90 or 95%, hospitals that are reducing things like falls and pressure ulcers by 70 to 90%, and so on. I think the thing that's frustrating to me is that it seems like on average things are getting better, but there's a wide variation where we have some people demonstrating great success and a lot of hospitals that still seem stuck in old levels of performance. So I'm curious what you think here, current day, what are some of the biggest barriers that prevent every hospital from repeating some of these same successes that we see in certain cases?

Robert Wachter: There are a lot of them, as you know from your work. I'd say the biggest one until recently, and this has changed recently, and I think it's exciting. Until recently, the pressure to improve was largely moral and ethical. And that's important. I think most people in healthcare are in healthcare for the right reasons and don't want to harm people. But as we've come to learn how hard this work is and how much system change it involves and how that requires substantial amounts of resources, you're just not going to get there unless the institution is making a significant investment in making it better. And if you are a hospital or a clinic and you're going to get paid precisely the same, whether you deliver high-quality or poor-quality care or safe care or unsafe care, then it's unlikely that you're going to make that investment. And I think that was the state of affairs until fairly recently. Three to five years ago, Medicare paid the best hospital and the worst hospital in the country exactly the same. Now that's not true. Now there's about a 5 to 7% payment that's at risk based on your performance, and that's going up pretty quickly. So what that means is that boards and CEOs and other leaders now have a significant business incentive that links to their moral incentive to pay attention to this. And I think that's what you see. I think you see organizations beginning to focus on this, give it the attention that it deserves, give it the resources it deserves. And now we're seeing kind of the usual bell-shaped curve of some of them are figuring it out more quickly than others because it's hard. It's not like you decide this week that we're going to focus on providing a safer environment or causing less harm and next week you're going to make a difference. It's really a three-to-five-year journey. When you look at the places that have made significant progress, they'll tell you that they've been working at this for five to 10 years. And then there are other places that really just started a couple of years ago.

Mark Graban: So last question before we dive into The Digital Doctor, I'm curious what your perspectives are on the interface between Lean principles and practices and the modern patient safety movement. Do you see or hear about things that are working well and do you have any concerns or suggestions about all of this?

Robert Wachter: Yeah, you know, I find Lean to be extraordinarily interesting and I'm not an expert. It's really only come to my own organization, UCSF, over the last couple of years and I've seen real successes and I've seen some challenges. I think part of the reason that it's come to many organizations fairly recently and it was not kind of, it was not baked into the original formula that most organizations use to attack patient safety is that I think people tend to see it as an efficiency maneuver and a waste reduction maneuver and tend to see that on a different axis than patient safety. And as you've said and written, and I really do believe they are very tightly intertwined, but I think we didn't approach it that way. I think we approached patient safety as, “Let's understand what our hazards are, where we're seeing harm around the organization. Let's analyze it case by case. Let's try to put in place a plan, an action plan that deals with that thing that we saw last week and then let's see how it works.” And sort of the techniques to do that were generally PDSA kind of cycles. The original approach was really the kind of one-off. “Let's analyze each error one at a time and approach it in a silo.” I think a healthy movement in the patient safety field over the last five to seven years was in some ways the rebranding of patient safety as not being about errors so much as being about preventable harm. And that created a little bit of a different worldview which was to, rather than focus quite so much on the individual error–the dramatic “we cut off the wrong leg” or “gave a kid an antibiotic that he was allergic to”–looking around the organization more systematically at harms that the literature tells us could be prevented. And that then led to a more systematic approach to attacking the issues. But still, in most organizations, I think Lean was seen as being too ambitious, too kind of organization-wide, too structured for many organizations to embrace. And I think what we're seeing now is because of the pressures now on efficiency and cost, which really only re-emerged over the last three or four years–they certainly were omnipresent in the mid-'90s. And then we all decided we didn't like managed care and they kind of went away for about 10 or 12 years and we were in a fantasy land like, “All right, let's just pay attention to quality and safety and maybe a little bit about patient experience, but let's not pay any attention to cost.” Now the cost came back. I think Lean emerged as probably the preferred technique to approach it. And as organizations began to embrace Lean, I think they are beginning to see that it's relevant for improvement in all sorts of domains, including patient safety. So I think we sort of backed into using a Lean approach to patient safety. It certainly was not, other than a few very forward-thinking organizations, it was not in the playbook in the early years of the patient safety field. And I think that probably was a mistake in that organizations that have embraced Lean and used it effectively see that it has all sorts of benefits in all sorts of performance improvement domains, including patient safety.

Mark Graban: Yeah, and I think that wasn't an all too common situation where I think it's maybe a combination of some people were, I think incorrectly, describing Lean as being all about cost and all about efficiency. And then I think there were a lot of organizations that were really just looking for a cost type solution. So there was kind of a, in a way, a match there in terms of goals that might not have been as balanced as they should have been. And I think a description of Lean as an approach that maybe wasn't as holistic or correct as it really is. So thank you for…

Robert Wachter: Yeah, let me say one more thing about that, which is I think it's easier for organizations to approach issues piecemeal than it is to try to change kind of institutional practice around improvement. And so, you know, when the safety field emerged, yes, people said, “All right, let's do PDSA cycles, let's try some kind of standardized method to improve our performance.” But that wasn't the crux of the matter. In most organizations, I'd say, including my own, that was not a huge institutional investment and imperative to come up with essentially a business model for the way we do improvement. The real change was to come up with an organizational approach to attack a new target, which was harm or errors. And that was a big deal in and of itself. So I think organizations felt like, “Our plates are pretty full just trying to attack errors, harm, evidence-based practice. More recently, patient experience.” And it was only, I think, two things that have happened in the last few years. One is because of the imperatives on cost and waste, people have begun thinking about Lean as an important technique. And then if they've gotten that right, have seen that Lean may be applicable to all of these other problems. And I think the second is that disappointment set in that they came to realize that even with an institutional imperative to attack targets like harm or patient experience, if you don't have an institutional language and methodology for attacking these things where everybody's on the same page, you're not going to be very good at it. And I think that's… it was sort of that gap that people saw. I'd say those two things came together–the cost imperative and the recognition that what they were doing was not working very well–that have led a lot of organizations to embrace this.

Mark Graban: And going back even to Lucian Leape and Don Berwick and others who were learning from Dr. Deming, I mean, I think Deming taught about the need to look at an organization or to look at the whole system instead of looking at silos and pieces. And that's a powerful message. But I guess if that were easy, we would all be in systems thinking learning organizations.

Robert Wachter: I think that certainly was my feeling. I embraced the idea of systems thinking. And I remember the first edition I wrote of my patient safety textbook. It's really all about systems thinking. It's about thinking about errors in a new way. But I'm not even sure I mentioned Lean in that. I wrote it maybe seven or eight years ago. It was not really on the radar screen of the patient safety field. The patient safety field embraced this idea that errors are not caused by individual bad people. Most of the time they are system glitches. But I think in terms of a systematic method for moving from, “Okay, we got that,” to, “What are we going to do now?” I think we were a little bit fuzzy on that.

Mark Graban: Yeah. Well, so maybe that's our transition here to talk about The Digital Doctor. And maybe problems with software or clumsy implementations are also system problems and not the fault of bad apples either. But the subtitle of your book is interesting: “Hope, Hype, and Harm at the Dawn of Medicine's Computer Age.” And maybe we can delve into each of those. But I'm curious to hear first. There's been so much hope and hype in the last couple years, but healthcare, a lot of areas of healthcare have been really slow to adopt modern software systems. And I'm curious what some of your thoughts are about why healthcare maybe had to be incentivized or dragged into a world of electronic medical records and electronic health records.

Robert Wachter: Yeah, I think some… first of all, even just hearing you say that, it is extraordinary that healthcare, which is almost one-fifth of our economy and arguably the most complex and information-intensive industry that we have, and where the stakes are probably higher than any other, embraced paper and pencil until very recently and required $30 billion of federal incentive money to get us to become a digital industry. Just on the face of it, that's kind of shocking.

Why did it happen? I think part of it was the absence of the screwy incentives that exist in healthcare that do not place the same pressures that every other business has to figure out how we deliver the best quality, safest thing at the lowest possible cost. I think those incentives drove every other industry to use technology tools effectively. And those incentives are so mixed and kind of bizarre in healthcare that I think that was part of the problem. And then you have kind of a vicious cycle which is wiring a 6 or 700-bed hospital like my own is an extraordinarily complex act. And if there is not a business incentive for the hospital to buy a system, then you're not going to see the software companies enter the field and develop the kinds of programs that you need, nor are you going to see what really needs to happen, which is version 1.0 leads to 2.0 leads to 12.0 because this is too hard to get it right on the first shot. The first time it's clunky. And then people use it and give feedback and you improve and you iterate and then it gets better. So all of that stuff, which is really the history of software design in every other field, that dynamic was really not true in healthcare. And I guess the final thing is if you were a 26-year-old tinkering in a garage and in Cupertino working on the next new great software product, you're not going to work on a hospital electronic health record system. The regulatory environment is too complex. Healthcare is not a problem that you see in your own life. You see the need to develop the new Snapchat or Instagram. So all of those things kind of marbled together I think led to this, what was really an enormous business failure and market failure, which is the market did not push the healthcare system to go digital. And the federal government ended up deciding that it needed to enter the fray and put in a pretty large amount of incentive dollars to get us to do it right.

Mark Graban: So $30 billion in stimulus money under the high-tech act that was spent for EHR adoption. I'm curious from what you found or what you talk about, what are some of the pros and cons of that kind of really fast burst, flood of money, flood of new technology? How did that play out?

Robert Wachter: I believe it was the right thing to do. I believe that politics sometimes is the art of the possible. And if you buy the premise, which I came to buy, which is that this was a market failure, healthcare was not going digital quickly enough and that if it was going to go digital in an effective way, there's no way to get to step Z without going through much of the rest of the alphabet first. So to me it was sort of, you had to start somewhere, we had to create a tipping point and it was not happening on its own. So then you come up with, all right, how's this going to happen? Think about the political environment in Washington. Try to find $30 billion anywhere to do anything and get that through Congress. It's an impossibility. And so the art of the possible was in 2008, the economy imploded. There was a $700 billion stimulus package to prevent a depression for “shovel-ready projects.” And some smart health policy folks were there and said, “Here is our one chance.” And I believe it was the one chance. I believe that if that chance had passed, there is no way in a million years they would have found 30 billion or even $5 billion to do this.

So my own feeling was this was a smart move politically and against its main goal, which was to get healthcare to go digital. It worked. If you look at the percentage of doctors' offices and hospitals that had electronic health records and were really fundamentally digital–everybody had some computers lying around, but really fundamentally did their work in a digital environment–that percentage in 2008 was 10%. Today, it's probably north of 70%. And not only is this sort of an electronic health record issue, but I remember when I interviewed David Blumenthal, who was the head of the federal health IT czar at the time all this happened, and I said, “Well, David, people have said because the federal government got so involved, you stifled innovation.” And he said, “Are you kidding me? Go down and spend a little time at some of the companies in Silicon Valley.” And he was absolutely right. Because the market now for health IT goes well beyond electronic health records. There were billions and billions spent last year on startups in health IT. A young kid coming out of Stanford, MIT, today is actually thinking about developing IT tools for healthcare. They were not thinking about that. So I think what the federal government did with their investment was legitimize, create a market, legitimize the market, get us over the hump and create an environment where we're now practicing a different kind of medicine. We're practicing digital medicine. We weren't before. So that's the good news, and I think it is largely good news.

The bad news, and I'm not sure this was anybody's fault or could have gone very differently. First of all, the systems are clunky. So here's the history, here's the pushback I hear periodically, which is, “They should have waited until the systems were better.” Well, no, the systems were not going to get better until people actually bought them, used them, pushed back on the company. New entrants came in the field and said, “Epic or Cerner, they're okay, but they don't do this and that, here's my product and it's better.” That's happening today. It was not happening before. So this idea of waiting till the products were better was not going to happen. The second pushback you hear is on interoperability, which is the existing software is often relatively closed. It would be great if everything talked to each other. It would be great if we had the App Store. Again, I think that coming out five or six years ago and saying that's the first thing we're going to do would have been a mistake. I think the first thing you wanted to do was get everybody on computers and using decent systems and getting used to it. And the next thing that you do, which is now, is to say, “All right, UCSF, you've got a computer system and you're using it for everything. Paper is gone, you're seeing benefits, and you're on Epic. So you talk to other Epic places, which is good because there are a lot of them. But if a patient of yours is hospitalized at a non-Epic place, it's pretty tough to get the information around.” Now you have the federal government kind of knocking people's heads together and saying, “Now it's time folks to play well together, create the kind of structure that allows you to have interoperability.” So I think again, it would be nice to be there today. I think it was unreasonable to ask for that on day one. And final sort of negative is when the federal government decided to put $30 billion into it said, “Well, we also have to regulate this market because what a scandal that would be if we gave hospitals and doctors tens of millions of dollars and it turned out they bought computers and stuck them on a shelf and never used them.” So they said, “We're going to have to regulate this. We're going to have to make sure you're buying good systems that do good things.” And how you feel about this partly may depend on what your political stripe is. But even as a good San Francisco Democrat, I think the Feds went too far. I think that they had to be involved in the early days here, and the involvement is a program called Meaningful Use. They had to be involved making sure people bought the computers and were beginning to use them in effective ways. But you start creating a regulatory apparatus against something like technology, you start having the federal government dictating things like fonts and how the machines work, basically do their work and think about if the Feds were dictating to Apple what the iPhone should look like, or dictating to Google what their search should do, it just, it doesn't work. And I think that the Feds have come to realize that there's a lot of pushback. So I think that Meaningful Use program went way too far.

Mark Graban: Yeah, well. And you say you're a San Francisco Democrat. I'm sitting here in Texas where, as they say, even the Democrats are Republican. The things that jump out at me, though, in the book when you talked about the regulation or this most recent, I believe it was the second wave of Meaningful Use about doctor's offices or hospitals having to share their discharge instructions and that they're just kind of broadcasting them out to all sorts of organizations and sending faxes or electronic messages that I think the lean thinker in me, I'll set politics aside. The lean thinker in me would say, “What waste!” If they're just saying, “Well, hey, we're checking that box. You said we have to blast it out to people whether they need it or not.” That seems silly.

Robert Wachter: I think that's the issue. One of the fun parts about doing the book was once I got into it, I realized the only way to do this well, and in an interesting way, was to talk to people. My wife's a journalist, and when I told her the idea of the book, she said, “The only way to do this is to do it journalistically.” So I went around and I interviewed about 90, close to 100 people. And what I came to learn was not that surprising, which is these are largely good, smart people. The federal policymakers, the CEOs of the tech companies, the primary care doctor trying to do her job in Dubuque, Iowa, the patient on a peer-to-peer community site. These are all good people. But people see the world from their perspective. And if you're a federal policymaker in the Beltway, you think, “Sure, let's just this standard, it's not that hard to meet. And it's going to make the world a better place.” My advantage was then to go to the primary care doctor in Dubuque or go to the chief medical information officer who's now spending all of his or her time just trying to check those boxes. And you see the amount of silliness and the amount of box-checking and gaming that's involved in just meeting the federal standards. And that's when you come to realize that I really do believe that the Feds had a crucial role here and should be praised for what they did early on. But the history of technology and complex technology, I think most vividly illustrated by the Internet, is the Feds were very involved early on. I mean, the Internet would not have happened without the Defense Department and DARPA. But fairly early in the game, they said, “We better pull back and let the community run this thing.” And that was an incredibly smart and sage thing to do. And I think that's the stage we're at here where it was really important that the Feds were involved early and it remains important that they be involved in areas like security and privacy and involved in trying to promote interoperability. But they had gotten so far in the weeds and the amount of wheel spinning and box-checking rather than innovating was just too strong. And I think the time has come for them to pull back.

Mark Graban: Well, before we jump into maybe one final question here to tie things back together between patient safety and healthcare IT, I will make a comment about the book that I do think you succeeded in writing it in a journalistic fact-finding approach that you weren't writing it as an advocate one way or another, that there was, I think, a lot of balance in the book about the things that are working well, the things that are challenges. And maybe a last question on that sort of pro-con analysis of what's happening. One of the things that jumps out to me again and I think we would agree patient safety is a non-partisan issue of looking at how this flood of information technology in some ways helps prevent certain types of errors and protect patients. But there are new and sometimes different risks that get introduced. In the book, one thing that stood out to me, if you can tell the story briefly or at least reflect on it, the 16-year-old patient who was given 39 times the correct antibiotic dose. And to me I look and say, “Well, this is classic system failure.” It's not just a technology issue. It involves human factors and workflows and just one of those classic sad situations where things line up very badly. So I'm curious maybe if you can touch on that story and maybe reflect on net net. Is the technology making things safer even if there are some new and different risks introduced?

Robert Wachter: Yeah, well, let me start with that, which is the answer, I believe, is unambiguously yes. And part of my goal in writing the book was to make clear that I am not a Luddite and believe deeply that we have to computerize healthcare. I'm not really shocked that it's been harder than we thought. But that's kind of what got me into this was if you were working in the field of patient safety for the last 15 years, as I have been, we've all been waiting for computers to be our savior. And as we were waiting, Google developed search and Evernote came out and OpenTable came out and Twitter came out and the iPhone came out and the App Store came out. And so it was logical for us to believe that once we finally computerized, it would just be magic because it's such magic in the rest of our lives. And so what really got me to want to write the book was as I looked around, seeing that nobody's really talking about the challenges, the workflow, the culture, all the difficult problems that were emerging. The books and articles about health IT were often sort of aired on the hypey side to me. And so I wanted to sort of, I actually wanted to write something for myself mostly. I wanted to try to understand what was going on because I just found it so interesting and just remarkable to see what was going on.

And that case that you mentioned was really what got me to write the book. I was sitting at a meeting at UCSF about a year and a half, two years ago, and we were talking about a case where we gave a kid a 39-fold dose overdose of a very common oral antibiotic called Septra. The kid's correct dose, which everybody knew this was a dose that he was on when he was outside of the hospital as a chronic dose for him was one pill twice a day. And through a series of glitches, sort of the first one being just a mistake, which is not that hard to make, of prescribing with the computer set on milligrams per kilogram rather than milligrams, the doctor puts in an order for 39 of these pills. Now that's a glitch that's going to happen. In some ways that's not the most interesting thing. The most interesting thing is that we have a safety system. And we now have a safety system embedded in a state-of-the-art, you know, I think arguably the best computerized system that's out there with barcoding. And we also were in a fantastic hospital with smart, competent people who are very caring. And there were about five or six opportunities for this error once it got generated by that first wrong order to have been caught. But in a classic, you know, people I think probably know the Swiss cheese model, all these layers of protection that fail. It was classic Swiss cheese, but now computerized Swiss cheese, which I had not seen before. I've been studying Swiss cheese for 15 years and keep saying, “Well, a computer would have fixed that, a computer would fix that.” So the nature of this was, “Okay. An alert fires and the doctor ignores it. An alert fires for the pharmacist and the pharmacist ignores it.” The pharmacist is working in a space the size of a Winnebago with three other pharmacists while trying to deal with alerts coming up on every other medication. The alerts are unbelievably over-exuberant. And people of course do what people do, which is they just stop paying attention to them. In the old days, then that order now for 39 antibiotic pills would have gone to a pharmacy technician who would have picked up a big jar of Septra and started pouring it out. And about halfway through, probably would have said, “What the hell?” and stopped and tapped the pharmacist on the shoulder and said, “What's going on here?” But now it goes to a $7 million robot. And when you tell a $7 million robot to fetch 39 antibiotic pills, it says, “Thank you,” and it does it. And then the final step, which was really the most interesting one, was it went to a young nurse who was floating on an unfamiliar floor. The usual cultural issues of not wanting to look dumb and not feeling like she really had permission to stop the assembly line and pull the cord and check. And she then said, “Well, this is really kind of a screwy order. I've never heard of anything like this, but I don't know, maybe it's right.” And “I know to get to me it had to go through a doctor and a pharmacist. And I have this piece of technology that will check and tell me for sure if it's right, called the barcode.” But what I hadn't realized until I analyzed this error was at that stage of the medication safety process, the barcode's job is to defend the order. The barcode's job is to make sure the nurse gives the order that the doctor and the pharmacist have endorsed. And so she barcodes pill number one. And the barcode machine now says, “No, that's not right. I need to see 38 more.”

Mark Graban: It verifies the error.

Robert Wachter: It verifies the error and makes people feel like, “Okay, that must be right.” Just to give you a sense of how screwy this is, this would be the equivalent of driving down the road and seeing a speed limit sign that said, “The speed limit on this road is 2,500 miles per hour.” And the nurse knew that. When I interviewed the nurse, I interviewed all the involved participants, and as you can imagine, they all feel horrible. They're all good people. And the nurse said, “Yeah, I knew it was sort of weird, but I just, you know, the system around me kept giving me signals that it was right.” And so that was part of what led me to write the book and why the term “harm” is in the title. Because there's no question that the computers are making care safer and better. And they'll make care even better and safer as the systems get better and our processes and human factors wrapping around the systems get better. But they are capable of breathtaking harm if we're not careful. And that's part of why I wanted to share that.

Mark Graban: Yeah. And, you know, the things that jumped out to me were, like you said, the human factors of, you know, the pharmacist saying, “Well, you know, I know that doctor who put that order, and I know that doctor's good. So there must be a research… there must be some new protocol being tested.” And the nurse asking the patient. The patient saying, “Well, I don't know.” I mean, it seemed like there was just a lot of points where somebody it was easy to rationalize, “Well, this must be correct.”

Robert Wachter: Right. And we're used to seeing that in lots of errors. And when you put yourself in the position of the person in that moment in the culture, in the system, you can sort of understand how they would do that. I think the real difference here is the degree to which technology, which we've been counting on to be our savior, has now created a new set of potential hazards. And this is not unique to healthcare. One of the things that was fun for me in doing the book was I spent a lot of time talking to people in aviation, arguably the most advanced field in technology and one that's really figured out a lot of stuff. But talking to Captain Sullenberger, who landed on Hudson, spending a day at Boeing. They are struggling with this too now, because it's a fundamental problem with technology. As the technology gets better and better, that's good. But people begin to turn their brains off and trust the technology at times when they shouldn't.

Mark Graban: And final question here, in the aftermath of that story. And the patient was okay, it sounded like.

Robert Wachter: The patient had a grand mal seizure and spent about an extra week in the ICU. So it was pretty terrible, but luckily survived.

Mark Graban: Didn't die but survived. So the patient as the victim. And in healthcare, sometimes people talk about the term the “second victim” of, like you said, all of these great people in a system who didn't mean to make an error, they're caught up in that Swiss cheese effect or a bad system. It seemed like, at least the way the story was told in the book, that there was a distinct, at least, I hope, lack of blame and lack of firing or punishing anybody and instead trying to learn from what happened to improve.

Robert Wachter: That's correct. None of the people were fired. All of the people, to their immense credit, agreed to talk to me about the case. They didn't want their name used, but they were completely open and honest about it. We have decided as an organization to be open and honest about this case because we came to realize that this was not a unique UCSF event. People are seeing this throughout the country as they embrace these new systems. And, you know, I don't think you can fix this sort of thing if you hide the ball, if you basically say, “We don't want to talk about this.” So it's so dramatic and so interesting that I'm really quite grateful to all of the involved participants, including the mother and the kid who was the victim of the error, for deciding that it's really an act of tremendous charity to be open and honest about this.

Mark Graban: Yeah, well, and I'm grateful you were able to share it. I'm grateful for your new book, The Digital Doctor, also for past books, including Understanding Patient Safety and another book, Internal Bleeding. I highly recommend those. And the other thing I'm going to recommend and link to in the show notes is a blog post that you wrote, Bob, about trying to find the right balance in not being a completely, you know, not leading with blame, but not going to the other extreme of being completely blame-free, of trying to find the right balance of accountability. I thought that was well-written, and I'll share that with folks. I don't know if you have a comment on that real quick, since I brought it up.

Robert Wachter: Yeah, it's been a struggle I've had for the last five years or so in patient safety. I think we kind of embraced this idea that it's all about bad systems. It's never about bad people. I think that was a wise thing to do in the early years of patient safety, particularly as it pertains to doctors. Because if the patient safety field had started and we didn't say that, you would never have gotten buy-in from physicians, because a physician hears “error” and there's an automatic inkblot test and all the physician can hear is “malpractice, malpractice, malpractice.” So we began with the notion that it's all about systems and never finger-pointing, never blame. And I began struggling five or six years ago with feeling like that's mostly right. But what do you do with the person who decides they don't want to use the surgical checklist or they don't want to clean their hands? And I would go to hospitals and they would tell me, “Well, we have a 50% hand hygiene rate here.” And I said, “What are you doing to fix that?” And they said, “Well, we're working on the system.” And I'd walk around the hospital and I'd say, “The system looks pretty good. You have gel dispensers every three feet. And there are pictures of clinical leaders cleaning their hands, looking like they're having a party.” And when they told me a 50% hand hygiene rate was a system problem, I hate to say it, but my BS detector went off because I think the problem there was an intense lack of accountability for performance. People were choosing to ignore reasonable safety rules. And I think it's time that we rebalance that a little bit, which is why I've been focusing on this for the last few years.

Mark Graban: Yeah. Or sometimes leaders will hide behind saying, “That's a system problem.” But, you know, I think, maybe wrap things up on the Dr. Deming reminiscing again. Dr. Deming always said, “You know, you can fix the system. Leaders are responsible for the system, and let's work together to fix that.” So I appreciate everything you're doing to try to help fix our healthcare system. Again, our guest has been Dr. Bob Wachter, talking about The Digital Doctor. And I want to thank you so much for being a guest today.

Robert Wachter: It's a great pleasure. Really enjoyed it.

Videos of Bob Wachter:

On Waste — Safety, Quality, and Cost… including some comments I particularly agree with that an over-reliance on financial incentives and penalties can cause problems and Lean/TPS can help focus, in a systematic way, on what hospitalists really care about: the patient.

A longer keynote address on patient safety:

Feedback & Comments:

If you have feedback on the podcast, or any questions for me or my guests, you can email me at leanpodcast@gmail.com or you can call and leave a voicemail by calling the “Lean Line” at (817) 372-5682 or contact me via Skype id “mgraban”. Please give your location and your first name. Any comments (email or voicemail) might be used in follow ups to the podcast.

If you’re working to build a culture where people feel safe to speak up, solve problems, and improve every day, I’d be glad to help. Let’s talk about how to strengthen Psychological Safety and Continuous Improvement in your organization.

[…] Update: Here is the podcast. […]

I highly recommend this excerpt from Bob’s book… the story about the 39-fold overdose and some mentions of Toyota, Lean, and the andon process:

How Medical Tech Gave a Patient a Massive Overdose