My guest for Episode #353 of the podcast is somebody whose work I've appreciated for a long time — Quint Studer. I was first introduced to his book Hardwiring Excellence back in 2005 and I've been following his work (and reading his books) ever since.

Today, we'll talk about “hardwiring” and other concepts from his first book. We will also explore his latest book, The Busy Leader's Handbook: How To Lead People and Places That Thrive, a book intended for leaders in all industries.

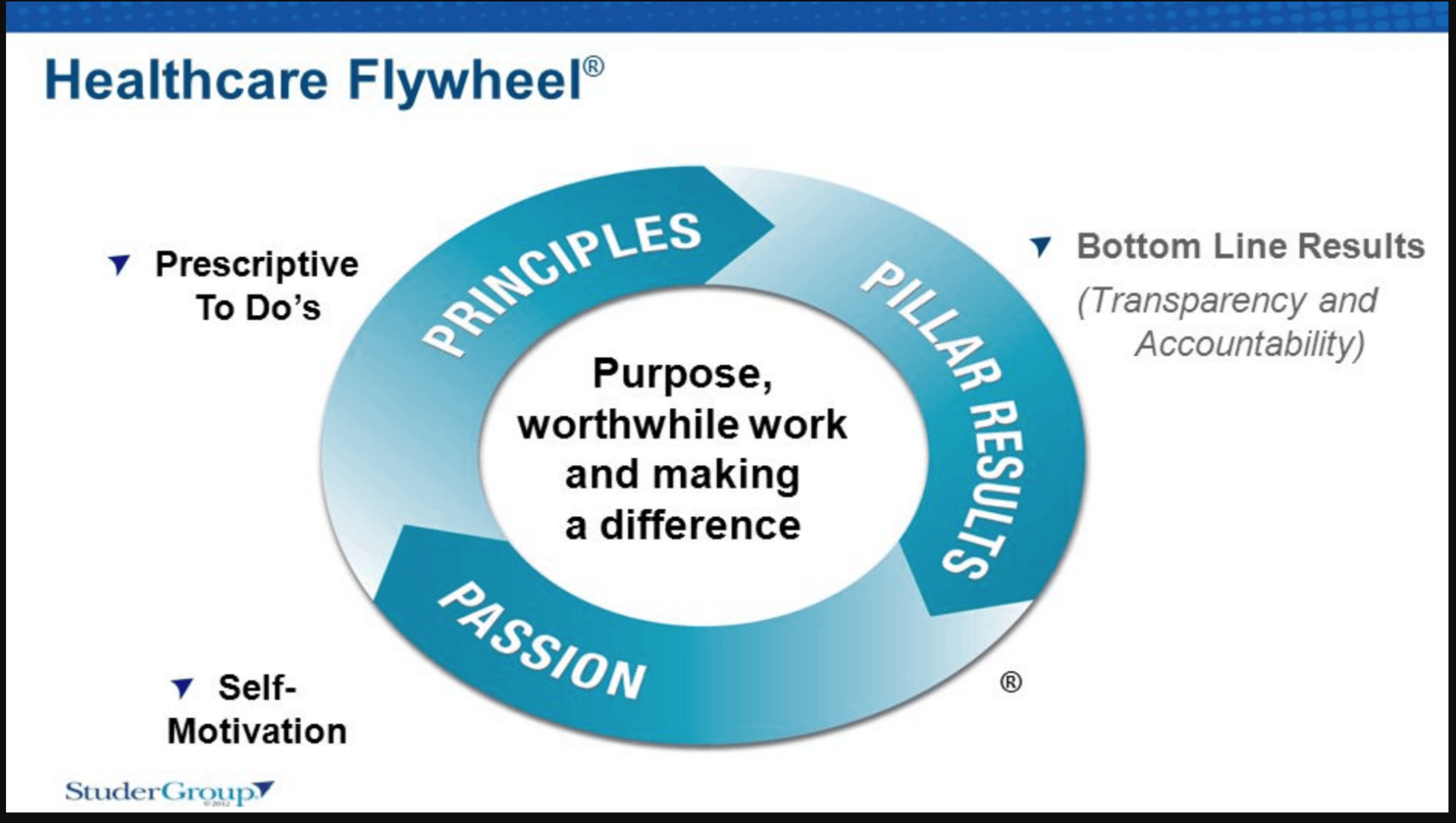

In this episode, Quint reflects on his journey from special education teacher to hospital president to founder of Studer Group, always guided by the principle that leaders must diagnose before prescribing solutions. He discusses how to hardwire practices into daily work, the importance of humility, and why leaders too often fall into the trap of being “too busy to improve.” His “flywheel” concept shows how small, consistent actions create momentum and sustain results over time.

We also explore themes from The Busy Leader's Handbook, including servant leadership, coaching managers instead of rescuing them, and building accountability without micromanagement. Quint shares stories from healthcare and even his role as co-owner of the Pensacola Blue Wahoos minor league baseball team, illustrating how timeless leadership lessons apply across industries.

Streaming Player:

For a link to this episode, refer people to www.leanblog.org/353.

For earlier episodes of my podcast, visit the main Podcast page, which includes information on how to subscribe via RSS, through Android apps, or via Apple Podcasts. You can also subscribe and listen via Stitcher or Spotify.

New! Subscribe and listen with Spotify:

Questions, Topics, and Links:

- Quint, when I first started working in healthcare in 2005, I can't count the number of people who recommended your book Hardwiring Excellence. Can you please tell the listeners about your experience that led to the writing of that book?

- What does it mean to “hardwire” practices in a workplace?

- One other powerful idea from the book is the “flywheel” – what is that and how to leaders get that momentum started? How to break the “too busy to improve” cycle?

- From Laura on LinkedIn:

- “I would love to hear his take on how leaders can hardwire rounding tools and asking team members what needs fixed without them “owning” everything. Sometimes the easier thing to do is take the fire and put it out but lean would encourage empowering the team.”

- When leaders are out in the workplace and try to engage with employees, why is it important to add, “It's OK, I have the time?”

- Why are leaders so busy? Why are they often too busy to try new things?

- You write about leading with humility… that's also a core Toyota theme. Can a leader become more humble over time? If so, how?

- From Sabrina on LinkedIn:

- “I would love to hear Quint's approach of how to create a culture in which leaders support employees like described in your post.”

- What have you learned about business and leadership as the co-owner of a Minor League Baseball team, the Pensacola Blue Wahoos?

Transcript:

Mark Graban: Again, we are joined today on the podcast by Quint Studer.

Quint, how are you today?

Quint Studer: Great, Mark. Thanks for the opportunity.

Mark: I'm real excited that we have the chance to talk. Before we talk about your new book, The Busy Leader's Handbook, when I first had the opportunity, the privilege, to start working in healthcare back in 2005, everywhere I went, a lot of people were recommending your book, Hardwiring Excellence.

I really liked that book a lot. It was really helpful and inspiring. I saw that there were a lot of connections, I think, philosophically to lean management, so I was happy to have that first exposure to you.

I was wondering if you could tell the listeners who maybe don't know your background a little bit about your career and experiences that led to the writing of Hardwiring Excellence.

Quint: Sure. Ask me a question that should take 10 minutes, and I can take 10 hours, but I'll do the best I can.

I started out as a special education teacher. People ask me about that. I think that was the best gift I've had. I didn't know I was going to be doing what I did.

As a special education teacher… and I think this fits lean, it fits everything…the first thing you do is you diagnose the child. I've seen one of the mistakes that businesses make is they read a book or hear somebody speak — it could be me. Then they rush off to start putting tactics in place because they'd make sense, but they'd not diagnose.

You diagnose a child. Second thing you do is you set a high goal for the child. You want to create as much independence as possible. You get everybody on the same page. What I mean by that is, you get the teachers, the parents, maybe the occupational therapist, everyone on the same page.

You want consistency working with that child. You do a ton of reward and recognition. You look at processes that the student can learn.

Mark, being you're expert in lean, probably one of the early lean people in education was a guy named Mark Gold, at Southern Illinois University, that created a step-by-step process on how to take apart and put together a Schwinn bike brake of 10 parts, and show that people that were considered severely disabled could do it. He did it by building, sequencing step-by-step.

Then you also have some consequences. When I got into healthcare after 10 years in special education, I put that into play. I put that same philosophy. You diagnose, then you try to set goals. You get everybody on the same page and you look at your processes.

I got into healthcare and kept going through the road. Got promoted with little or no training.

Then one day I ended up in the inner city Chicago hospital with very little money. I was given an assignment to move patient satisfaction, getting you diagnosed. I drove, because I was in Chicago, to South Bend, Indiana. Spent the day at Press Ganey, really learning their tool, how it worked.

Came back, and then I benchmarked. I went to Southwest Airlines, because they had a great reputation for service. Saw what they did. They told me I needed to train managers and get employees involved, and did that. We got a lot of luck. I went to Baptist in Pensacola and duplicated it.

Did some research on two hospitals that had great satisfaction. One was Holy Cross, one was Baptist. Then I started Studer Group. Learned a lot along the way. Wrote Hardwiring Excellence.

Really, it was my love note, in a way, to middle managers, who I think have the roughest job in all businesses, of ways that they could put some tools in place to be more successful.

Along the way, I created various tools on consistency and urgency. Then when Studer Group was sold to Huron, I basically resigned from there. Have been spending the last four years working with small businesses and communities, and dabbling in healthcare a little bit still, too, with permission from Huron. Again, I'm continuing to learn.

Mark: Yeah, that's great. There's a couple of things maybe we can unpack a little bit from what you said there. For one, the idea that you bring up about not just rushing to implement tactics. I think that's a common tendency in organizations, in healthcare, and beyond.

That could include lean. That could include tactics that come Press Ganey. I guess, ironically, that could include a rush to implement a tactic or tactics from what's, I think, come to be known as…you can call it Studer Group Principles or Studer Principles.

Let's say you're faced with a situation where you see an organization is just rushing to implement something. What would you do to try to coach those leaders about stepping back and helping them understand the need to first diagnose the situation?

Quint: Normally, Mark, you and me, when you come into an organization, they're trying to do it on their own. I'd say 50 percent of the people that came to my talks or my two-day conferences came there with the thought, “I'm going to listen for two days, and then I'm going to go home because I'm going to do this on my own, because I'm not going to pay him that much money to do stuff that we should be able to do on our own.”

Then 99 percent of the work came from organizations that had failed to do it on their own. Here's what I find — where they miss. They don't do a basic diagnosis, which — I created a tool. What's the urgency? How does it go through the layers?

For example, one of the questions I would ask people through different layers of the leadership is, if this organization stays the same over the next five years — same processes, same tools, same techniques, same productivity measures…The only thing we can't say will stay the same is our revenue — but if we stay the same internal to the operation, will our results be much better, better, worse, or much worse?

Usually the senior leadership team, Mark, will say, “Gosh, dang it. If we stay the same, we're going to be much worse.” Minimally, they say maybe 75 percent much worse and 25 percent say worse. Yet, when you go down to the frontline supervisor, about half of them say, “We can stay the same.” So you have the crack-the-whip mentality.

The first thing I look at is, does everybody understand enough data to have seen enough diagnosis to at least know they can't stay the same with lean?

I was at Valley Health System in New Jersey, one of my favorite places, and they did this survey, and the CFO was stunned, because everybody so much thought they could stay the same. He basically showed them, “If we stay the same, based on Medicare and Medicaid and self-pay, we're going to take a profitable organization and in four years not be profitable.”

A big part of it is this, I'll say. Number one, do they have the right accountability system to hold the game? Reading your book, Lean Hospitals, if somebody comes in, you put in a better system, but a year from now, that manager's not being held accountable for the outcomes of that system — because your job wasn't to put in better processes — it was to put in better outcomes — so we'd say, “Do you have the right accountability system? “Do you have the right training?”

Not just training to that tactic, but if I don't know how to run a meeting, I'm wasting a lot of time. If I don't know how to hire better, I don't have the right hires. If I don't know how to get rid of people, I have people in there that are going to implement. Do I have the right skill set?

Then the third thing, which I think you and I are talking a lot about, is do I have the right sequence? Franklin Covey research says somebody can put in about two changes. If I change two behaviors, I have a pretty good chance of pulling it off. Three, I reduce it in half, and four, I'm down the tubes.

Most of the time, when I go into organizations, I would try to convince the CEO, which is hard, because the ego's there, “You might have to say you went too fast. You got to go back and regroup, because you've moved so quick, you haven't, as we call it, hardwired, or baked into the DNA, that this is what they've got to do.”

We just did that. I'm on the board of a great organization called TriHealth in Cincinnati. Mark Clement loves to move quick. I've known Mark forever. One of the things as a board member I pointed out to him was, “You might want to back up a little bit.” He did. He was grateful.

Those are things that I've found. I think sequencing is where hospitals and health systems or small businesses get messed up. They try to go too fast.

Mark: Yeah, I see that a lot in the context of lean. I think there's different ways of saying similar things. You talk about sustaining improvements or hardwiring improvements.

Part of what I hear you saying is, it's too late — is it too late to think about hardwiring after we've implemented something? Do we need to think about from the get-go how to prepare for hardwiring? I imagine diagnosing and getting alignment around the need for change is probably a key contributor to being set up to be hardwired. Is that fair to say?

Quint: Yeah. I think one of my favorite articles… I got into Chicago in 1993, with Mark Clement, who is now at TriHealth. We're in the bowels in this cultural transformation. We're pretty excited about it. James Collins came out, his book Built to Last.

We're really cool into this cultural transformation, and then, darn it, John Kotter put out a book, or an article, in 1995, from the Harvard Business School, that says, “Why Cultural Transformations Fail.”

You're right in the middle of it, and he tells us it's going to fail. He talked about the fact that 70 to 80 percent of most changes, whether it be lean or anything else, will fail, and they don't have to fail.

It's a 1995 article. I encourage anyone to go online and look at it. It's called, “Why Cultural Transformations Fail.” The first two points they make is do you have the right burning platform?

Change is hard on people. Why do they need to change, why do they want to change, and why don't they have any choice in change? The other one is do you have the right guiding coalition?

I think, sometimes, the guiding coalition… Senior executives think they have the guiding coalition, but it's not big enough. That's why you have to bring people into the loop so you have that critical mass. Those I wanted to burning platform and critical mass.

Mark: One of the really powerful concepts from Hardwiring Excellence is the idea of the flywheel and the idea of trying to build momentum that then becomes more self-sustaining.

I'm curious your thoughts are…If you, for one, can talk about that flywheel concept. How do you help break…In a way there's almost a negative flywheel in a lot of organizations, where leaders say, “Yeah. We need to improve, but we're too busy to improve,” so we get stuck in that cycle of, “We're too busy to improve.” At worse, it becomes more overwhelming.

How do you shift the negative momentum into a positive flywheel momentum?

Quint: It's interesting you say that, because we just did this EntreCon for small businesses here in Pensacola. There are some people from outside Pensacola, but, basically, more Pensacola.

I called the CEO, who didn't send anybody. I was stunned. I said, “You never sent anybody.” He goes, “We're just all so busy.” It's like, “We're too busy to get better, so we know how to manage our busyness,” like, you've been around, Mark forever, where organizations say, “We just don't have time to send people away for training. Does that mean we're going to keep doing it the way we're doing it, which isn't working.”

It's sort of insanity, at times. When you look at the flywheel, then I'm an imitator. I take things that other people have done and I tweak them.

James Collins in Good to Great showed the flywheel, which was passion — figure out what you're really good at and then get the economic result that you need so you can keep sustaining it.

I put a hub in the flywheel, which was purpose, worthwhile work, and making a difference.

I think that good leaders, no matter what business they're in, figure out how to help their employees see that what they do is a vital part of the job, from a coffee shop to a candy store to a book store to a big business. How do we connect with the employees on why what they do is vital?

The other thing is, with the middle of the why, is why are we doing what we're doing? Because, if we can't explain the why, we're going to lose the employees. It's like what your kids used to say, “Why? Why? Why?” and it's, “Because I told you to.”

You've got to get to the point where you've got to connect, because true leaders create a culture where employees do it because they want to do it, not because they have to do it. However, sometimes you have to create the “have,” because, if I have to do it, then I see the outcomes, and it makes, “Oh, gee!” It makes a lot of sense.

Years ago, I got a call from Floyd Loop, who was the CEO of Cleveland Clinic. He's passed away now. He's one of my huge idols in healthcare. He called me up one day and said, “I did a Quint Studer today.”

He said, “I was in at the restroom, and the maintenance guy came to clean it.” He said, “I lean up to him and told him how important it is for bathrooms to be clean. Thank you very much.” Fred is so unassuming, said, “I was really surprised, because he knew who I was, and, wow, it made a big difference,” so I think sometimes people underestimate their power.

If we look at that, then a key to the flywheel is most people have the passion. You go into a place, Mark. You know that the O.R. wants to be better. You know the place wants to cut out waste. You know they want to cut out steps.

They have the passion. What we do in healthcare, any business is we've created cultures based on negative feedback. When I do my conferences, even today, I'll say, “If your boss calls you or texts you right now and leaves a message, ‘Contact me when you can,' your first thought isn't, ‘Here comes more reward and recognition.'”

We have a restaurant in Pensacola called McGuire's. I used to do training here. People would go eat at McGuire's, and the biggest selling T-shirt healthcare people would buy was the T-shirt that said, “The beatings will continue until morale improves.”

I think it's how do you build on their strengths and that three to one, three compliments to one criticism. Your second point is the skill building. Have you really invested in your managers to have the skill?

You know, Mark, you go into an organization. Of course, I've seen unbelievable great results with lean. I've seen organizations take out waste, take out steps, and employees were really pumped about it. But, to that manager, you've also got to help them beyond that.

What are some other skills that they need to give them time back, whether it's handling a top conversation, whether it's figuring out cost of goods, whether it's figuring out how to discuss compensation, opportunities for growth?

We really want to give that manager enough training so they have the time to do some of those things. Then, when they get the results…People asked me — I'm sure they've asked you, Mark — “How do you sustain the gain?”

By getting them results. When you get results, people are so excited. They want to keep going. They don't want to stop. I think that's how the flywheel was meant to work, to be a self-sustaining DNA in an organization.

Mark: There are a lot of parallels in what you're saying to what we might hear from Toyota or what we might describe as lean leadership, that leaders need to help build capabilities, leaders need to help set direction.

Coming back to what you were saying earlier, employees, I think, often, they want to do good work, but they may have gotten comfortable with the situation. They might be afraid to take on something new, and they might be afraid of criticism.

That's why I think what you're describing is so powerful, the role of leaders to help get that process rolling, to get things unstuck, if you will.

Sometimes, unfortunately, you hear leaders blame employees for not being on the bus, or whatever analogy they're using. The one thing is, you're really strong. What you've written and said over time is that it comes back to servant leadership.

That's another really important part of the Toyota philosophy, and lean management. I was wondering if you could talk a little bit more about servant leadership, and why that's such a necessary approach, to really have an excellent organization.

Quint: Sure. Before that, I want to talk a little bit about change. Some years back, when Regina Herzlinger from Harvard asked me to come to a session on, “What are the key leadership skills that they should be teaching at the Harvard Business School?”

It was interesting, because the number one skill that we came out with was change. Yet, when you go to cities, communities, or small businesses — again, I'm doing a lot of work now with communities — and you ask people how much training they've had in change, they really haven't had a lot.

If you look at change, there's different quadrants of change. I've always thought that the person that has the greatest advantage in adapting to change in an organization is the new, inexperienced person. They've never gotten into the habit of doing it the other way.

Then there's the relatively new, “Yeah, I can make this change. But I have been doing it for so long that it's baked into me, so I can handle the change.”

The third quadrant is, “I've been doing through this checklist. It's more comfortable to be doing it the way I'm doing it. But yeah, if you make this adjustment, it will be uncomfortable but I can handle it.”

Mark, I have found the person that struggles with change the most is the person that's been sitting there the most successful at the current method of the way they're doing it. They're so used to it, that they do it.

If you look at certain leadership, it's trying to understand where people are on the change spectrum. I've just had a talk with a fellow from Cox Media, because I'm going to be up there talking about change in a couple of weeks in Atlanta.

The question is, we have to even have great empathy for the person that's experienced, that's always been doing it a certain way, because they're multi-tasking. When you're a servant leader, you're basically trying to understand where that person is in their own life, with their own change.

I think you've got to try to go where they're at with the whole empathy. Then you've got to figure out, “What barriers do I need to remove for them to be successful? How do I reduce their anxiety, because they're afraid of failure,” and then, “Do they have the skills that they need to be successful?”

I was lucky enough to be invited by the Walton Foundation in Arkansas, to talk to a Heartland Summit they had. They had the president of Walmart talk about the change they're going through. To get them ready for change, their change management expert had them take their watch and put it on the other wrist for one week. The audience were fidgeting, “You're not going to make us do that, are you?”

Leaders miss the obvious — and I write about this a lot — that they're a role model, and people are going to watch them. They have to make sure they understand the basics. These are, sounds like the basics, but you don't get yourselves…

One of my big ones at Baptist is, when I came in, my office needed furniture, for sure. People asked me if I wanted new furniture. I said, “No, just find some stuff in the storage area, and I'll use whatever is sitting in the hospital,” because how can I spend money on me when we need better wheelchairs, when we need blood pressure cuffs?

I only told that to a field maintenance guy, but that got around pretty quick. Parking, don't cut line. Your job is to create the right culture for people to optimize their human potential.

I joke all the time, Mark, when I was young, I wanted to be the president of a hospital so I could make my own schedule, to have this cool parking spot. Dang enough, by the time I got there, they didn't flip the chart upside down, so I had to park farthest away from the hospital, blah-blah-blah.

It's just how you're creating the right culture to help other people achieve their potential. Dang enough, that's not a great feeling, to see other people being successful.

I love the fact, Mark, when I look on LinkedIn or something, there are so many people that came to my training that I knew, that were administrative residents, directors, and VPs, that are now running healthcare systems. It's like a coaching ladder. It's pretty cool to see their success.

Mark: Speaking of LinkedIn, I asked some people on LinkedIn if they had questions that they wanted me to ask you. I want to share one of those because it's on this theme of servant leadership, and “I work for you, as a leader.”

Laura asked, “I would love to hear Quint's take on how leaders can hardwire rounding tools, and asking team members about what needs fixed, without them, as leaders owning everything?”

“Sometimes it's easier to just take the fire and put it out, but lean, and I'll add other approaches, would encourage empowering the team. What are your thoughts about finding that balance, of being a servant leader without feeling the pressure to do it all, or creating dependency, perhaps?”

Quint: It's perfect. I just had a two-day conference, this was our big topic. We get promoted into leadership positions because we bring solutions.

If you look at who gets promoted, it's the employee that somehow comes up with some solutions. Now, the reason we got promoted is, as an employee, not as a leader, as an employee, we come up with solutions.

Now, as a leader, we somehow think that's our job to get the solution. The ego, including mine, gets sad. Even this, I'm going to give the topic, and then I'm going to feed my ego a little bit on it.

We fall into, what I call, park ranger leadership, where we keep rescuing people and we keep feeling good, because they thank us for rescuing them, but they keep getting lost because you haven't taught them how to quit getting lost.

The hardest thing for a leader to say is, “What do you think? What do you recommend? If you were me, what would you be doing?”

If the person says, “I don't know,” instead of then giving the answer, you say, “You know what, why don't you think about it for a while, a week or a couple of days, and bring me back what you think we should do.” It's almost unbelievable.

Here's an example, Cleveland Clinic, years ago, manager's up on the unit, says to the people, talking about things, and people were complaining about inventory. “We ran out of sheets, we're running out of towels,” and blah-blah-blah. At one time, that manager would've ran to her office and started looking at it.

The manager said, “What do you think we should do?” and they said, “Our census has been so much higher than we're used to. Maybe we should be re-looking at what our standing inventory is.”

The manager said, “Well, why don't you guys come back to me on what you think it should be?” We make leadership harder than it has to be, because we just tend to the solution people.

I was at a conference one time. These people, I wish I knew their name right now, and I'm sorry I forgot, but what they said was really cool. They said, “When you ask people what they think they should do, a great majority of them are afraid to take the risk, they'll say, I don't know.”

If you say, “Well, if you did know, what would you do?” she said, “70 percent of the people will then tell you something” because you've put a safety net in.

I also think, as a manager, you have to round often enough to play offense, because you're overwhelmed. I had a CEO say, “Quint, I can't do this rounding. I was up on a nursing unit the other day. I was up there for 40 minutes.”

I said, “When was the last time you were up there?” he said, “I hadn't really been up there in a long time.” I said, “Right, they don't know if they're ever going to see you again.”

I call it playing offense. You go on to that unit, and first you start off with, “Tell me what's going well today,” and then they look at you and say, “Is IT there?” “Is your systems there,” or “Is the staffing there?” and “Yeah, yeah, yeah,” because it's usually better than people think. They only talk to you when something's wrong.

“Who should I recognize today?” You hit those two positive things and then you say, the magic question is, “Do you have what you need today to do your job?” They're either going to say yes, and then you say, “Great!” and they're going to say no, and then you can go into, what I call, a solution conversation.

Mark: That's a great question. One other question that's always stood out from your book. I've passed it along, I've talked to leaders about this question, when they're going out. Whether you call it rounding, rounding with a purpose, gemba walks, whatever you call it.

Quint: Whatever it is.

Mark: Whatever it is. Leaders will try to engage with people, and employees might be timid for different reasons. The one question I remember you recommending is to not just ask the questions around, “What can I help you with? What needs to be fixed?” but to also add, “It's OK. I have the time.” I found that that's a very powerful practice.

I'm curious if you could share a little bit more about, why it's helpful for a leader to say something that seems obvious, “It's OK. I have the time to talk with you about it now.”

Quint: People have this issue with, “I don't want to bother you. You don't have the time” I can't tell you how many people will eventually contact me and say, “Oh, I didn't want to bother you,” or finally I'll see them, and they'll say, “Yeah, I've been wanting to talk to you, but I didn't want to bother you.” I say, “That's your issue, not mine. I'm available.”

What happens is — we learned this with nurses — you'd ask patients why they didn't tell the nurse this, or ask the nurse this, and they'd say, “Well, they're so busy.” Then, once the nurse started saying, “Hey, before I leave the room, is there anything more I can do for you. I have time,” it released that conversation.

Same thing with a leader. You're important. I have time. I'd like to really learn what's going on. I think we play defense.

We have a great hotel chain called High Plains, and I spoke to them last week. There are managers in hotels, and I talk about the fact that, as managers, we have to play offense a little bit. You have to be out there on the field, letting people know you're interested.

Then the other thing, Mark, is you've got to let them know you're going to follow up. I know this sounds crazy, when somebody writes it down…If you tell me something, and I look at you and I shake my head, you're wondering, “Are they going to follow up?”

If I write it down, whether it's on a phone, whether it's on an iPad, whether it's on a piece of paper, and then I come back with you, I'm building trust.

One of my favorite stories is, when I first got to Baptist Hospital, I parked far away. I'm walking in, it's seven o'clock or so, and I see a nurse. I introduce myself, and tell her I'm the new administrator of the hospital, and tell her, “I work for you.”

My favorite line used to be, “I work for you. What should I get done today?” They'd look at me like maybe a urine screen would be a good idea.

This nurse said to me — I loved her — she said, “I'm going to leave here in 12 hours. It's going to be dark when I come out to my car. Those bushes have overgrown, and I get scared somebody could be behind those bushes. Can you get the bushes trimmed?”

We went in, I called facilities, they trimmed the bushes, they actually fixed the fence a little bit.

She went back out that night, at 7:00 PM when it was dark, and she saw trimmed bushes. If you'd say to her, what do you think of the new administrator, she wouldn't say, “Well, he's really good at vertical integration, he understands population health, he's an expert in process improvement,” she'd say, “I like him.”

Our goal is to constantly be looking at removing excuses and barriers from people, while giving them the skills to be successful.

Mark: That's powerful stuff. Let's talk about the new book, The Busy Leader's Handbook.

We talked about, leaders are busy. You said earlier about writing a love letter to middle managers, they have the toughest job. Is this book also, in a way, that love letter, or something that's meant to be helpful for leaders at all levels?

Quint: Yeah. For years, people used to say to me, “Are you ever going to rewrite Hardwiring Excellence? Are you ever going to update Hardwiring Excellence?” A couple of times I tried, and then I started reading it. I liked the tone and the sequence, so I haven't.

I started putting this book together, and it's not Hardwiring Excellence, but the goal is the same, to give people, particularly skill sets and tools and techniques to, one, reduce my anxiety.

When middle managers, or anybody, reads this book, the first thing they're going to do is feel pretty good, because they're going to find out that they do a lot of things pretty close to what I recommend, or what I recommend.

First thing I want them to do is not be so defeated, because people go home with what they can't do instead of what they can do. If I have 100 employees and 98 of them are doing well, it's those two that aren't doing well that I take home with me every night.

I want them to get out of the book…I want to reduce their feelings that maybe they're not good, because they are. They're in a role that's vital. I want to help them with their self-confidence.

Number two, I want to reduce their anxiety, that, “How do I handle this situation? I've got a tough conversation coming up, how do I handle it?” I want to reduce their anxiety.

Number three, I wanted to give them a desk guide that they can go to, because here's what I've learned. I can take people off-site every 90 days, for two days, and we can talk about all sorts of stuff, everybody likes it, but I'm not going to use it until I need it.

If you talk to probably any woman, the great majority of them will say, “Some day, I'm going to have baby.” They might even had a health class in high school that talked about pregnancy, but they're probably aren't going to get connected to it till they're pregnant, and want a little bit more.

I wrote a book that a person can certainly read all at once, but I wrote a book so you can get in and say, “Hey, here's what's going on right now? How do I create a more safe environment for employees? How do I measure what's important to us? How do I become more self-aware? What do I do when I'm feeling stressed?” I wanted to write a resource guide.

Also, John Maxwell, about a month ago, they asked him what's his favorite book. He said, the one he's currently writing right now.

That wasn't me. My favorite book for years was Hardwiring Excellence. I've had other books, and people say, “Quint, what book should I read now?” and I'd say, “Well, read Hardwiring Excellence.” It's still my favorite book.

I'd say, The Busy Leader's Handbook is now my favorite book, because it takes some of the concepts I wrote years ago, but brings them up to today. It has a lot more tools. I've learned a lot. I've learned so much more now of what managers face. I could write a book on, what do you need to know now.

I'm very pleased with the book and I appreciate the way Wiley's pushing this in all the airport bookstores. I appreciate what they've done to help get it in the hands of people.

Mark: It's a very scannable book. The table of contents makes it clear, if somebody's got a particular challenge, they can jump right to a chapter and find something that's useful. That intended audience is busy leaders in any industry, right?

Quint: Yeah, any industry. I was real sensitive to that. It's interesting too, because in healthcare, people actually get a lot of books that aren't for healthcare. If you look at some of the books they read, remember, gosh! Who moved my…That's how we were going to fix healthcare for about a year, everybody was going to read the book, Who Moved My Cheese?

Mark: It was trendy.

[laughter]

Quint: Then we were going to get gung-ho, and then we were going to run a nuclear plant, and then we were going to run a ship, all sorts of things. This book's meant for any leader. It is for anybody on a leadership role or a manager's role.

Chapter one, Mark, is so vital, and you talk a lot about it. Let's face it, what you've been trying to do over your years is like pushing an elephant up the hill here, because in order for people to put lean in, their ego has to be deflated enough to think that they've got to change, and they've got to trust somebody else.

Healthcare is particularly hard, because healthcare's fields are terminally unique, “Well, we're not this, we're not that, we're not this.” Chapter one is the key to this whole thing, is you've got to deflate the ego.

When Mark Clement at TriHealth said, “You know what, we've been moving really quick,” and by the way, he's been getting some unbelievable results there too, but even with unbelievable results, being named one of the top systems in the country, he still had courage enough to say, “…but in a few areas we've probably got to slow down a little bit.”

That's an ego deflation, and that's that self-awareness. We get self-awareness sometimes on our own. We get self-awareness on measurement, we just take our employee engagement survey.

One of the things we struggle with is our employees not feeling they're getting opportunity for growth. It might not be growth as you move up in the role, but can we grow you in your own skill set?

We don't have that type of data. We can con ourselves and…I was just talking to Louis Gump, who's an executive at Cox Media. He said to me how Cox is family-oriented. When James Cox passed away — he started Cox — in his will, he told them, always take care of your employees. I thought that was beautifully wrote. How do you know you're taking care of the employees?

Louis then went through all the ways they measure where their employees are at. I can't tell you how many organizations are hypocritical, because they say, “Our people are number one, they're the lifeblood of the organization.” They say it, yet they don't measure it. If you don't measure it, how do you know what to do about it?

Mark: Getting a survey back that has honest responses that aren't what they would hope to hear, that might be a humbling experience.

On the topic of humility, you talk about the importance of leading with humility. That's core theme from Toyota as well. Does it take some sort of near-traumatic event that humbles a person? I'm always curious can a leader become more humble? Does it take some external trigger?

Quint: Sadly, that reminds me… I'm on the board of Betty Ford and Hazelden, great long-term addiction. In the old days, they'd say, somebody with addiction has to bounce off the bottom, lose their job, lose their family, lose their health, then maybe, maybe, they'll think they should something. Over the years, you try to raise that bottom.

Same with a leader. Sometimes you don't have to have that traumatic experience if you're measuring along the way. Sadly, sometimes it does take that. Hopefully, we don't.

For example, again, I have a property company, I have a baseball team, and so on. We measure all the time. I'm doing an employee engagement roll-out video here at 3:30 this afternoon. I'm going to show areas we need to improve upon.

By getting close and measuring on a consistent basis, just like the 30- and 90-day meetings, why wait till the employee quits? Why not say at their 30th day, “Is there any reason you would think about leaving here?” Let's do the exit interview before they exit.

You can reduce the pain and the ego deflation by measuring and looking at the key indicators. The best thing to do is deflate your own ego.

I tell the story, Mark, in a talk recently. I'd been working on this project for years, and I was sharing my results, and they came up to me and said, “I feel so much better.” They said, “You know, I've been trying to do this for this long, and here's where I'm at. Hearing where you're at after 10 years, I feel like my progress is better than I thought.”

What they were basically telling me is that, I helped them by telling them I was still not where I want to be.

Steve Ronstrom, years ago when he was president of the hospital at Eau Claire, Wisconsin, called me and said, “Quint, I'm having this problem here. What do you recommend? You travel the country.”

I said, “Well, Steve, keep calling people, because I've got the same issue at Studer Group that you have in your hospital, and when you get the answer, call me back.”

We're all on this journey together, and as soon as people realize that…

The other thing that's cool right now, and I didn't know I was going to talk about this, I've been working a lot on mentoring, studying mentoring. There's something now called reverse mentoring.

In my book, I talk a lot about young talent, how to keep young talent, because everybody says, “Well, they leave, they go away, they can't do anything with them,” that whining.

Young talent wants to be engaged, they want to be involved. Lean is perfect for your younger employees, because you're giving them a chance to come up with solutions.

Then the other thing, it's called reverse mentoring. Some of the younger people are so…We have a fellow here named Daniel Venn, who's in our baseball team, in my Double-A team I own. He's in-charge of social media. He is so good that he's teaching everyone know how to maximize social media.

The other thing is, we're missing some great opportunities for reverse mentoring.

Mark: I do want to come back to any lessons from the baseball team, because that's a cool thing you've gotten involved in. Going back to the fundamental question of the new book…and again, for the listeners, it's The Busy Leader's Handbook — How To Lead People and Places That Thrive.

Back to our core question, why are leaders so busy, or why is it that they feel overwhelmed with being too busy?

Quint: Because I don't think they have the skill set. Over the years, people get put into jobs, they get promoted. 95 to 98 percent of people that get promoted didn't go to graduate education on leadership. They basically were good at their job and they got promoted.

Dave Wagner, who's the president of the Zix Corporation, they're out of Dallas, who's now bought AppRiver, told me that he went from being an employee, to leading employees, to leading leaders. Now as the CEO, he's leading executives, and it's hard. I don't think we spend the amount of money on skill sets.

I got asked on it by someone, “Is this a time management book?” I said, “In a way, it is,” because the best way to give people time is to give them a better skill set, because there's the waste of time and there's the waste of mind.

If you look at this book, if everybody did this book, it did the 41 best practices or so, they would gain a ton of time back, because their meetings would be run better, they'd understand process improvement, like you said, to take the waste out, to make it more efficient. They'd understand when you have to fire someone instead of hanging on to them.

They'd realize how to manage customer service so they're not dealing with so many complaints. I want to give managers a better light, because when I was a supervisor, I didn't get any training, Mark, in healthcare, except one time. One time the hospital heard the union was coming, so we had a one-day training on how to be better leaders.

Until I got to Holy Cross Hospital in Chicago and Mark Clement, I had never had a system say, “We're going to invest 64 hours in training on you.” We have not been good at giving people the time to get better. They're not going to ask for it, because they're sometimes embarrassed or don't even know what they don't know.

In my book, Hardwiring Excellence, one of my favorite statements is, “You can tell the values of an organization on how much they put into training and developing their talent,” because how can you tell people you want them to do a good job, but not give them the time to develop their skill set?

That's what's sad about when I go to companies. We put people in these horrendously tough jobs that are so hard, we don't give them the training.

I used to tell CEOs if you're depressed, and think you have it tough because you got 10 direct reports or something, take about an hour, go up to Med/Surg, pretend you're the Med/Surg manager, managing 70 employees, 365 days a year, 24 hours a day, given their whole array of different physicians, different patients.

Then, in about an hour, you're going to come back to your CEO office feeling much better than when you left, because you realize that you've got a pretty good job. How can we not give these people the skill sets to be successful?

Mark: As much as I generalize it, this is a big challenge in healthcare, the lack of formal supervisor training, managerial leadership training. Sometimes it's a matter of time. Sometimes, unfortunately, it's one of the first things that gets cut from the budget in tight times, when it seems like that would be counterproductive.

Quint: It's the first one. [laughs] That, and travel.

Mark: Travel for training, or have the company buy a book for you, or a training class.

Quint: It's incredible, I've learned that. I used to love buying books for my managers, because it showed them I cared about them, I wanted to do better. I'm always amazed at these organizations that will say, “We're a billion-dollar organization,” but then they panic over spending small amounts of dollars for that.

The other thing, we fall into the trap too, I've learned this more and more, we think that there's a department that should be doing training. We have the human resource department, or we have an OD department, or we have a training department. Those are there to be helpful, but the key person that has to develop the people is the person who they report to.

I'm a huge believer, if I wanted to make a zillion dollars at Studer Group, I could've came in and said, “You guys aren't the problem, it's the employees. We're going to do massive training of all the employees.”

Now, I didn't do it because it wouldn't work, because what happens is, employees hear from an outside person, but then they go back and they look at their manager.

This whole idea of mentorship and learning how to coach…Harvard Business Review put out an article this week which was great, on, most managers don't know how to coach, but they can learn.

Mark: Yeah, I saw that.

Quint: I tell people, development is part of everybody's job. Your job is to develop the people that work for you. You don't say, even though you have a department in a big company, they're there to help you learn how to develop. They're not the developers. That's the other mistake that companies make.

Small companies don't train because they don't think they have the resources, big companies sometimes think that somebody else should be doing it, when reality is, your training development department should be training managers on how to do development, not that they should be coming to them for development.

Most do, most are sophisticated. Most training development departments, and the HR departments, realize that they've been pushed way too much to take on a role that they can be helpful in, but it comes up to that top executive to make sure that the people under him are being developed.

I used to say to the CEO, “Look over your team, who are your best performers?” and he'd be, “Oh, these three are great!” and I said, “What if the rest of your team were as good as those three?” “Oh my gosh! My life would be better.”

I said, “Then it's your job to get those rest of them to those three.” We're all developers.

Mark: When you talk about developing an organization, there's another question here from LinkedIn, from Sabrina, she wanted to hear about your approach, how do you develop, how do you create that culture where leaders support employees?

Quint: First of all, I measure the heck out of employees. They have no choice. I know this sounds tough maybe, they have no choice. I will be very patient with managers on everything except not feeling that they're doing a good job with their staff members.

One is, you measure it. Then once you measure it, you identify issues. For example, our issue recently is opportunity for growth. Then you talk to the managers about, “How do I help grow you?” Because if I role model with you…

Another area is communication. Then you talk about, how can you sit down with your employees and say, “Hey, wow, you don't feel our communication's very good? Thank you so much. I appreciate that. I truly want to be good. Obviously, I'm not sure how to do it right now, but I need your help. Could you identify what excellent communication looks like to you?

“Could you tell me what you need, when you need it, where you need it, how you need it? Can you help me understand a time when I haven't communicated well, or did I miss something I should've?”

I'd say, you let the employees create a template on what good communication is, then you deliver it. It's truly measurement, and we sometimes don't want to measure. That's where we're penny wise and pound foolish, is we don't measure. Then when we do measure, we don't do anything about it.

I went into a hospital one time, and the CEO of the system said, “Oh, I feel bad for so and so. He was president of a hospital. Because his employee results are so bad, he's taking it personally. I told him not to take it personally.”

I said, “I'd tell him to take it personally. That's his job, to make sure it is the right place to work.”

Going back to what she says, you've got to measure it. When you measure it, you can tell. I can go to an organization and they'll say, “Oh, turnover is bad with all our lower-paid employees, because Walmart's taking them all,” or blah-blah-blah. Then I'll study it. I'll find managers that have the same compensation level and the same corporate that don't have any turnover.

Then we'll study them. I find, Mark — and you probably found this — one of the harder things to do is get people to deflate their ego and go down the hallway to learn from somebody. They'd rather go across the country to a conference to learn.

When I was at Baptist Healthcare, we were looking at our pressure ulcers. We also had a nursing home. Our nursing home did a better job with pressure ulcers than the hospital. I talked to the nurses about, let's take a field trip to the nursing home, because they're doing a better job managing pressure ulcers than we are. They have long-term patients that are sedentary.

Not everyone was excited to get on the bus. I think that whole measurement and benchmarking people within your own realm, instead of saying why you're different, how you're alike. I'll finish it.

Patient sat, years ago, started measuring it, press gating. Michelle Lasko, who is now deceased, was a manager on one of the units. Her patient stat was better than anybody else. Don Gain, who was working me then, I said, “Go study her. Just don't go ask her. Go study her. Spend the whole week just watching her.”

About the third day, Don said to Michelle, “You know, Michelle, I notice every morning you go visit every patient.” She said, “Doesn't everybody do that?” No, nobody else was doing that. See, managers will also have a rough time. They don't get to see what others are doing because they're isolated.

You've got to create those best practice visits and that learning lab. As a nurse, or if I'm a barista, I'm watching other baristas and I can learn from them. If I'm a manager, I'm not watching other managers. You have to create that learning environment for them.

Mark: Do you have time for a quick question about the baseball team before we wrap up?

Quint: Please, please.

Mark: The Pensacola Blue Wahoos. Boy, I would love to talk more, but maybe just a quick question. I appreciate how you talk about continuing to learn. What's one key lesson that you've learned from running a business that's so different — in this case, a minor league baseball team?

Quint: That it's so much the same. It's just the same as having a hospital or anything else. Number one, you got to hire. We don't sit here and say, “Well, they're seasonal employees.”

Every one of our employees goes through a three-step hiring process, just like you would if you were hiring an executive or anyone else. It's selection.

Number two, it's constant measurement. We measure employee engagement twice a year, yet we measure turnover all the time. We measure sponsor satisfaction, group satisfaction, and fan. We do 3,000 surveys every single game to find out how we're doing with the fans.

I think it's a good measurement. I think it's good training. Then we do huddles. Every game, we do a huddle. Everybody finds out what we're doing well, reward recognition. It's pretty cool. The third inning of every game, we put employees up on the dugout and we talk about why they're being recognized today.

Then my cellphone number goes up. I get my cellphone number up on the scoreboard in the third inning. People can text me. It's sort of neat, because after we identify the employees that are being recognized, I start getting texts from fans saying, “Well, what about Susie? She's really good. She's over here. What about this?”

We win. We have the highest net promoter score in all of minor league baseball because we've just done the basics. We train people.

What's really neat, what I've learned, Mark, because so many of the managers that I'm dealing with now, I have people that are running departments that are 25 years old, 24 years old, 28 years old — which is really wonderful, because you find how motivated they are to learn. I think that's the mistake we make.

If you want to keep your young people, you've got to invest in them. You can't wait, say, or be patient enough to wait till they're in their 30s to go to their first meeting or their first training. I think that continuous training is just vital.

You have to teach them process improvement. They're the ones with fresh pairs of eyes. They're the ones that want to cut out waste. You can't wait. That's why your techniques, your systems, like what you've done over the years, I have great respect for it. You have to do it in private business. It's not just healthcare. It's everywhere.

Baseball's been a great experience for me. We do one other thing that nobody else does that's cool. We have a lot of scouts at these games.

Scouts have rough lives. They're in a hotel all the time. We give them free food, which most minor league teams don't give them free food. Then we give them a $30 gift certificate to go downtown while they're in town to have breakfast, coffee, or lunch on us. They get a personal note from me with my cellphone number.

Scouts will tell you at minor league baseball the best place they want to come to is Pensacola to scout a game. It's always looking at what can we do to make our stakeholders' lives better?

Mark: That's part of your community development commitment beyond the team, the work you're doing in Pensacola. You're supporting that as well.

Quint: We have 300 to 350 seasonal employees. We have about 22 full time. Going back to my background is special education. We are one big job development center. Your ticket's probably going to be taken with somebody with ICOM special talents. They'll probably take your ticket.

You'll know if they have special talents, because not only do they take your ticket, but they tell you they love you, and maybe hug you on the way into a game. You're going to see probably three to four people right off the bat that are in wheelchairs helping you.

We really take seriously job development, because we feel that we're job a development training center for the community.

Mark: That's fantastic. I hope to come see a game at some point.

Quint: Please.

Mark: I love going to minor league baseball games in my travels and would really look forward to doing that at some point.

Quint, I want to thank you so much. I feel bad. I think it was on me for not inviting you to a podcast a long time ago. I know you're busy. I'm glad that we've been able to…

[crosstalk]

Quint: Hey, rearview mirror. One thing I've learned from people, this is another leadership tip. I was talking to a very successful military person here in Pensacola. One thing is they told me it's really important if you move forward to put things in your rearview mirror.

Hey, I'm just glad we could talk now. I'm saying thank you on behalf of someone who loves healthcare. Thank you for the tremendous impact you've had and the fact that you keep thriving.

I'm shocked we've never been on the same plane. I'm videotaping Delta now. Delta has gotten so much better. Their captain comes out and talks to you. It's interesting. We just had the VP of Southwest Airlines, Julie Webber, in town talking about…They have 21 touch points, Southwest Airlines do, when they hire a new employee.

You can see the airlines that are moving in the right direction and you can also see the ones moving in the wrong direction. I know you and I are on planes a lot.

Mark: You're flying Delta, I'm flying American. I can say, from my perceptions, American Airlines does not have the Southwestern culture.

Quint: No.

Mark: You can see it when the employees are frustrated and they're being put in a bad position. I feel bad for them.

Quint: We just had that. We just had an employee from Wisconsin was staying at a hotel, because we have stores in Wisconsin. He got all gung ho about complimenting people. He got on an elevator recently, saw an American Airlines pilot, and went to compliment him.

The guy said, “Listen, we have a lot of problems. Don't fly American.” This was a guy on the elevator. No, I'm with you. You can tell those that do it and those that don't.

Mark: Thanks again, Quint. I hope listeners will check out all of Quint's books. Quint, the most recent book, The Busy Leader's Handbook — How to Lead People and Places That Thrive, I hope you're not too busy to pick it up.

Again, like Quint said, it's designed where if you're looking for inspiration or some tips, you can jump in to a part of the book and find a small batch of insight and help. Again, our guest has been Quint Studer.

Quint, thank you so much for doing this. Maybe we can do this again sometime.

Quint: I love it. Thank you so much. Thank you, Mark. Bye-bye.

Thanks for listening!

Please scroll down (or click) to post a comment. Connect with me on LinkedIn.

Let’s build a culture of continuous improvement and psychological safety—together. If you're a leader aiming for lasting change (not just more projects), I help organizations:

- Engage people at all levels in sustainable improvement

- Shift from fear of mistakes to learning from them

- Apply Lean thinking in practical, people-centered ways

Interested in coaching or a keynote talk? Let’s talk.

Join me for a Lean Healthcare Accelerator Trip to Japan! Learn More