Lean thinkers love their acronyms, I guess. PDCA — Plan, Do, Check, Act — is one of the classics. Or we could argue about whether it's PDSA — Plan, Do, Study, Adjust (the language I prefer).

Either way, Dr. W. Edwards Deming popularized this cycle as a way to bring the scientific method into management. Plan an experiment, try it, check the results, act (or adjust) based on what you've learned. Repeat. It's a cycle of learning and growth.

But in too many workplaces, PDCA isn't the norm. A more insidious framework exists, which could be called:

PDCYA — Plan, Do, Cover Your A**.

Or Butt.

This version doesn't show up in any Lean textbook. Nobody teaches it at conferences. But if you've ever worked in an organization where leaders punish problems instead of learning from them, you've seen it in action.

Why PDCYA Happens

In my book The Mistakes That Make Us, I argue that mistakes are inevitable — they're part of being human. What's not inevitable is large-scale failure. This happens (and is made worse) when leaders turn mistakes (even small ones) into shame, silence, or punishment.

In a culture of fear, people don't stop caring about quality, safety, or improvement. But they do stop sharing. They learn that speaking up gets you labeled a “troublemaker” — as one nurse once told me, after she tried to raise concerns about patient safety and was marked down in her annual review (and she's part of a pattern rather than being a rare exception).

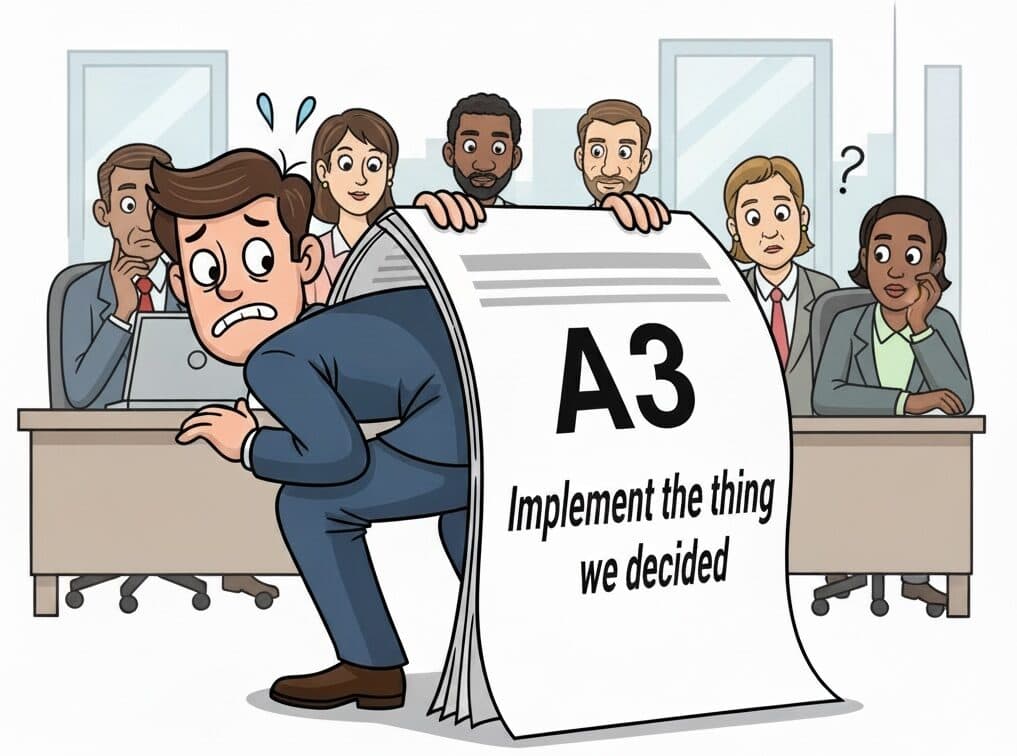

So, in this environment, the “Check” step in PDCA doesn't mean studying the results of your experiment — it means, for example, checking whether your name is on the report. Or checking that your action item is complete (whether it really improved anything or not). And “Act” doesn't mean adjusting and standardizing what you've learned — it means acting in ways that keep you out of trouble.

That's PDCYA in a nutshell. It's not a learning cycle. It's a survival mode.

PDCA vs. PDCYA in Action

This table summarizes what you might see or experience in PDCYA as compared to PDCA.

| PDCA Mode | PDCYA Mode | |

| Plan | Identify a problem. Brainstorm countermeasures. Engage the team. | Identify who to avoid. Draft three versions of the PowerPoint just in case. |

| Do | Test a new process for discharges and measure the effect on patient flow. | Wait until your boss leaves for vacation, then quietly revert back to the old way. |

| Check | Compare actual outcomes to your predictions. What do the data tell us? | Make sure your initials aren't on the “A3” |

| Act | Adjust the process. Spread the learning. Try again. | Archive the project in a folder labeled “Lessons Learned” that nobody will ever open. |

The Role of Psychological Safety

Amy Edmondson‘s research shows that psychological safety is the foundation for team learning. She defines psychological safety as defines psychological safety as “a belief that one will not be punished or humiliated for speaking up with ideas, questions, concerns, or mistakes.” In a psychologically safe workplace, individuals feel secure to express themselves without fear of negative consequences to their self-image, status, or career.

Some workplaces have proudly installed dozens of improvement boards — only for them to remain completely blank. Why? Not because staff were lazy or disinterested. It was, in many cases, because staff knew that writing down a problem was the fastest way to get blamed for it.

Contrast that with Allina Health, one organization that I worked with, where leaders deliberately engaged staff in daily Kaizen. Nurses, dietitians, housekeepers, and engineers all contributed small ideas–because, in part, they felt safe doing so. Managers didn't dictate; they coached. As a result, hundreds of improvements spread — saving money, reducing waste, and improving safety. Staff weren't covering themselves; they were uncovering better ways to work.

Data, Overreaction, and Covering

In my previous book Measures of Success, I argued that leaders too often react to every up-and-down in the data as if it's a crisis. That kind of overreaction breeds PDCYA behavior. If a single bad data point can lead to punishment, then, of course, people will spend more energy protecting themselves than improving the process.

Deming reminded us that most problems come from the system, not the people. Yet, if leaders keep asking “Who screwed up?” instead of “What went wrong with the process?” they drive the cycle of fear and cover-up, rather than learning and improvement.

A Tale of Two Cultures

At one hospital, a medication error reached a patient. The initial leadership reaction was to ask, “Which nurse did this?” Not surprisingly, nobody volunteered information. The investigation dragged on, trust eroded further, and the real root cause — a poorly designed labeling system — went unaddressed for months. That's PDCYA.

In healthcare, the well-worn (and common phrase) “naming, blaming, and shaming” describes all too well what happens after a mistake.

At another hospital, a nurse immediately reported a near-miss involving the same labeling process. Instead of blaming her, the manager said, “Thank you for catching that — what can we do to fix it?” Within a week, the team had tested and implemented a clearer label format. That's PDCA. One culture punished, so people covered up. The other supported, so people improved.

The Bottom Line

PDCA is a cycle of learning. PDCYA is a cycle of fear.

If your team is practicing PDCYA, don't blame them. Look at the system. Look at the culture. Look in the mirror.

Call to Action

At your next team meeting, try this simple experiment:

Instead of asking, “Who caused this problem?”

Ask, “What in our process allowed this to happen — and how can we prevent it next time?”

Then, notice the shift. People lean in instead of looking down. They speak up instead of shutting down.

That's how you begin moving from PDCYA back to PDCA — one safer question, one better response, one small cycle at a time.

Because the biggest risk isn't a failed experiment. The real danger is a culture where everyone is too busy covering their backside to improve the work.

Please scroll down (or click) to post a comment. Connect with me on LinkedIn.

Let’s build a culture of continuous improvement and psychological safety—together. If you're a leader aiming for lasting change (not just more projects), I help organizations:

- Engage people at all levels in sustainable improvement

- Shift from fear of mistakes to learning from them

- Apply Lean thinking in practical, people-centered ways

Interested in coaching or a keynote talk? Let’s talk.

Join me for a Lean Healthcare Accelerator Trip to Japan! Learn More