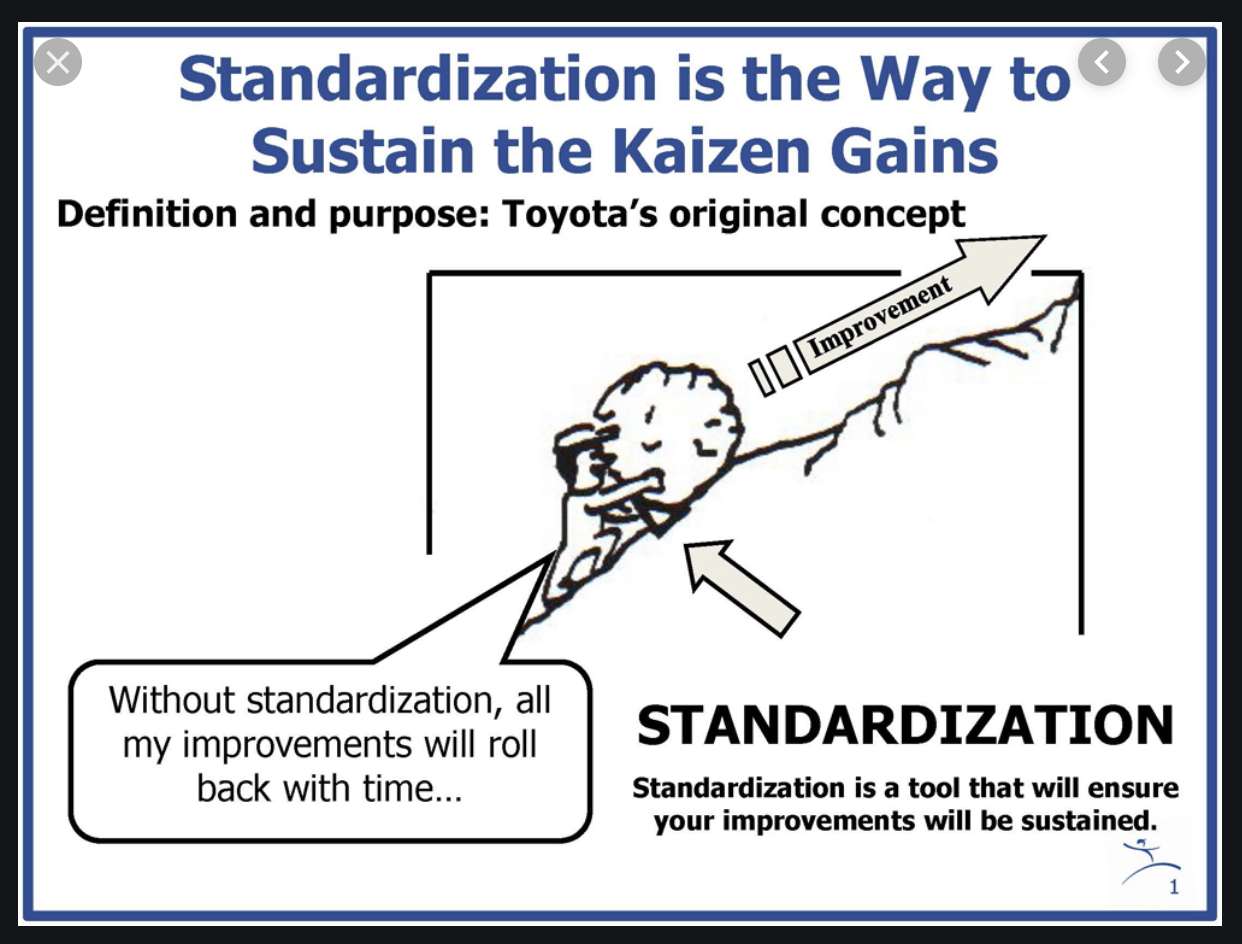

There are variations out there of graphics that are meant to illustrate how Standardized Work and Kaizen fit together. Kaizen is often articulated or illustrated in terms of “Plan Do Check Act” (PDCA) or “Plan Do Study Adjust” (PDSA) or whatever variation.

Before getting to the images (or “visuals” as some call them), let's talk about this more in concept — and maybe that illustrated how illustrations are needed or helpful?

The one notion is that Kaizen means progress… moving forward and bettering our performance. We might think of that as going up.

Then, many say that there's a natural risk of backsliding… performance drops, maybe that's because people go back to their old ways.

I think there are important questions of engagement and change management that often go unillustrated. If a Kaizen-based improvement is truly a “change for the better,” why would people go back to their old ways? Maybe they go back because they aren't committed to the changes or the new way, and maybe the root of that is a lack of involvement and engagement.

I don't know if “laws of entropy” really apply in the workplace. Blaming physical chemistry (and “laws”) seems to deflect attention (or blame) from our role as leaders or change agents.

I believe strongly that if we properly engage people in creating changes that are truly for the better, then backsliding is NOT inevitable.

Do we need to keep improving? Of course.

So, if you believe that backsliding is natural and inevitable (or if you blame workers for not buying into your change), then “standardized work” is often suggested as the way to “lock in” changes — to prevent backsliding.

I believe very strongly that Lean is not about forcing people to follow procedures and standardized work. We have to make sure that it's the right standardized work and that it's easy to do things the right way.

So, anyway, on to the graphics.

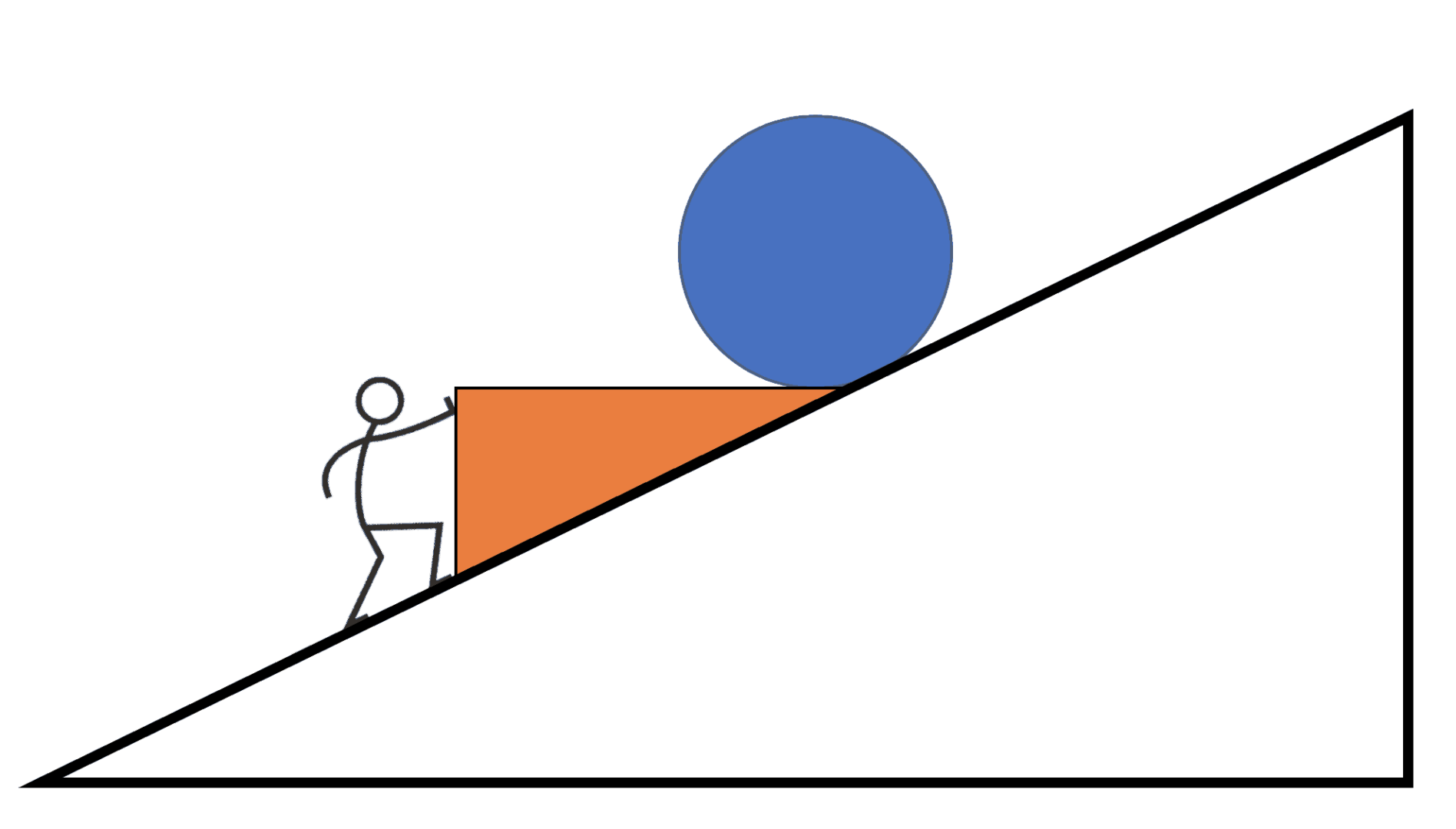

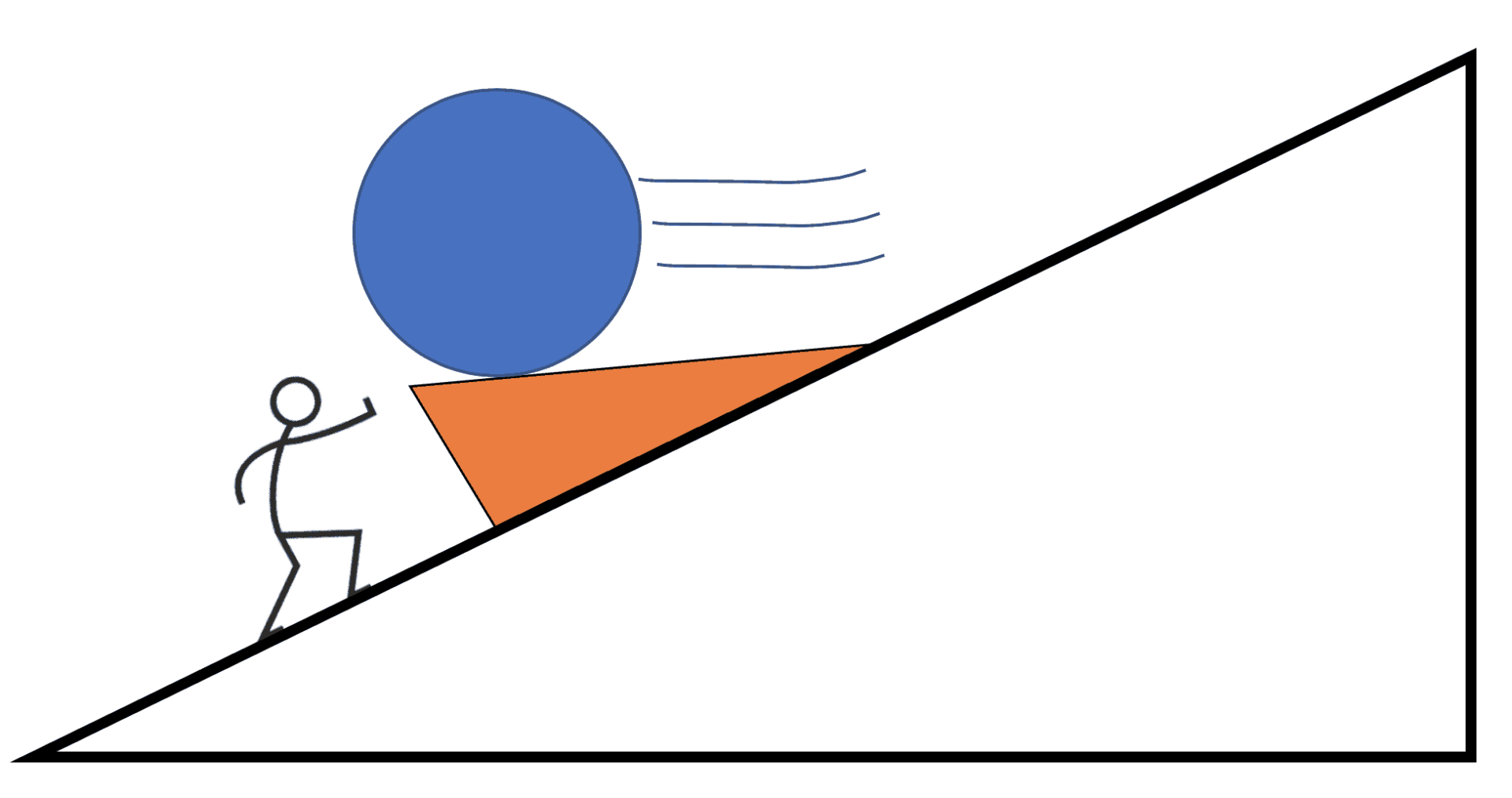

We usually see some sort of disc or sphere that we're trying to get up a hill. These are usually two-dimensional drawings, but there's something round-ish that we need to get uphill.

When I say “round-ish” there is a Lean Enterprise Institute graphic that shows a rock. It looks like a John Shook graphic that might have origins from Toyota:

Maybe surprisingly, that image looks like a safety and ergonomics nightmare — an injury waiting to happen!

We can't have that (and LEI and Toyota wouldn't want injuries), so people started illustrating standardized work as a “wedge” that locks in improvements. Sometimes, the wedge is labeled as something like “Lean Management System” (it's a versatile illustration, apparently).

The wedge is whatever you want it to be?

The wedge does the work formerly done by a person (except here)… it seems safer (or it's supposed to be) and it might be drawn like this (and the circle might be split into four equal quadrants of PDSA… which might also not be correct, but I'll blog about that later).

The wedge is probably poorly designed if a person has to hold it up, but I've seen it drawn that way. More on this later in the post.

Mike Rother has asked if it's “time to retire the wedge?,” as Mark Rosenthal blogged about here.

See Mike's slides about this via SlideShare:

Mike says, in a slide, that Toyota wouldn't blame a worker for some appearance of backsliding, which I appreciate. Instead of not “slipping back,” we should continue moving forward. Let's not keep things static… I agree!

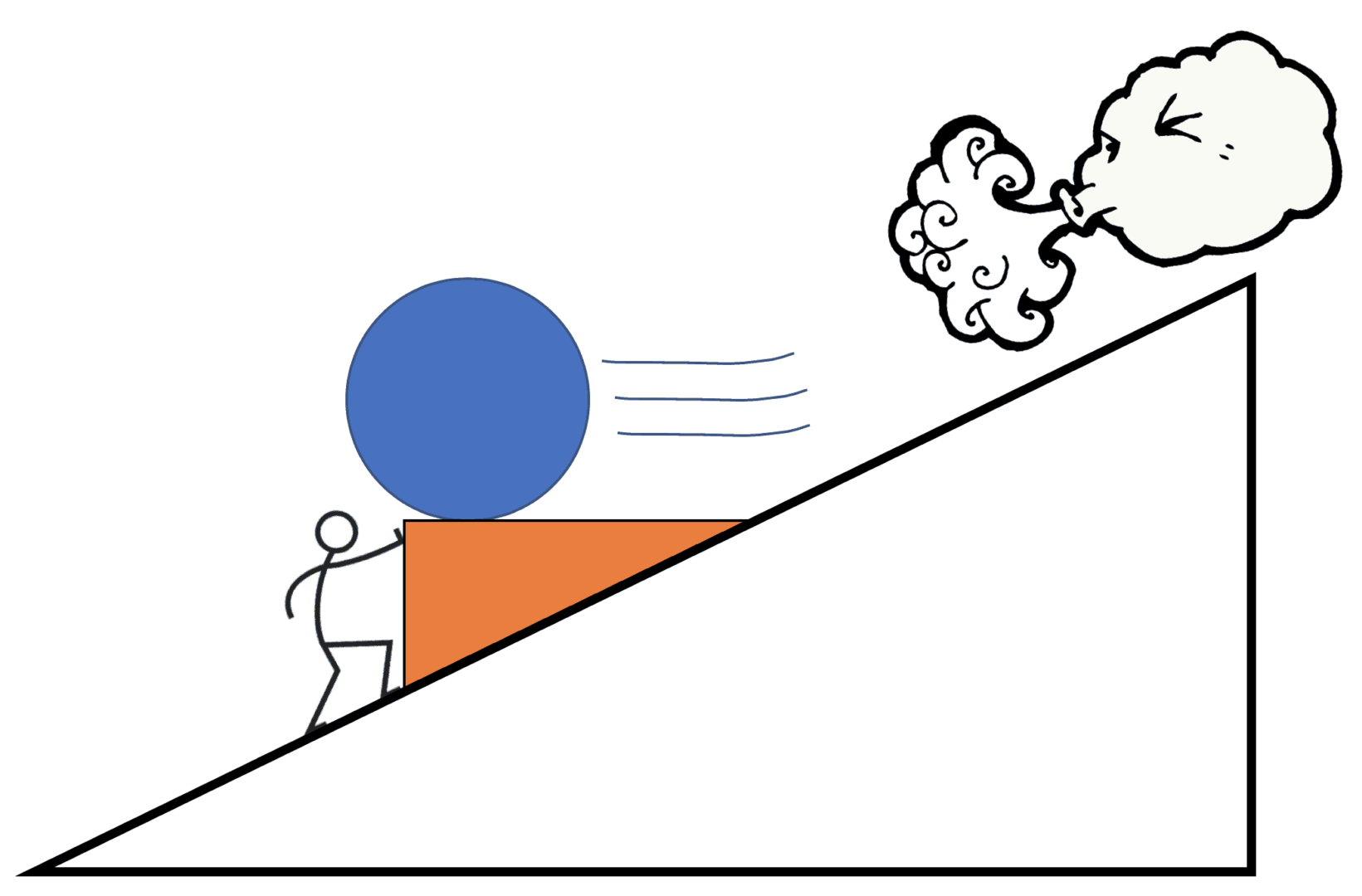

Back to wedges… I've seen some that are drawn like this:

I don't understand the physics of that one at all. Is that wedge really wedged into the ramp or the mountain that the boulder is sitting on? That stick figure looks a bit concerned perhaps. Maybe he has a hammer to really pound in that wedge.

That looks perilous!

Maybe I'm obsessing over the wrong thing… but if we're going to use illustrations, we should make sure the physics are sound.

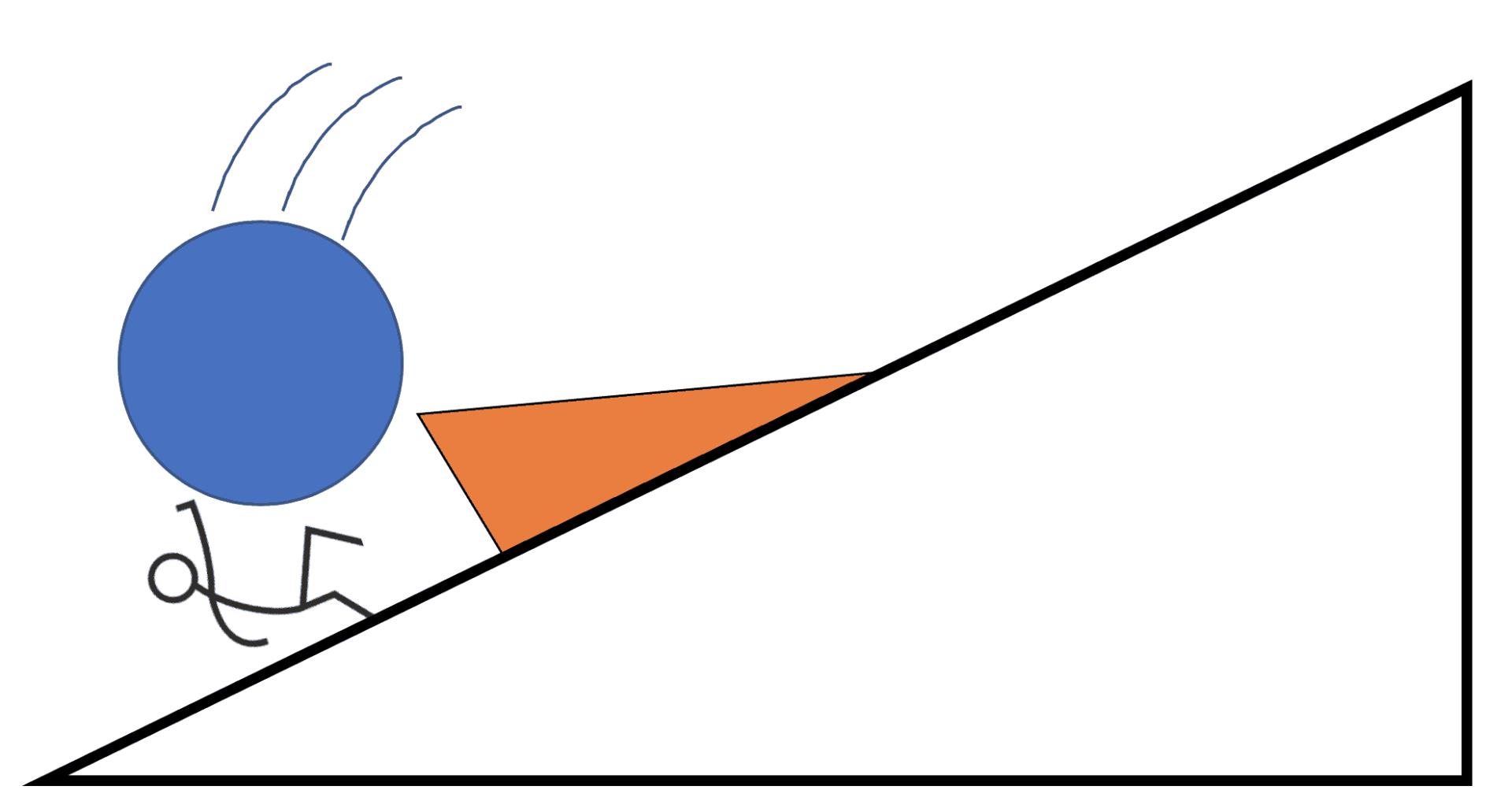

Some wedges are drawn like this:

Maybe that wedge from the previous drawing has fallen… what's holding up that round rock?

This seems like an “Oh No, Lean Leaper!” moment, ala Mr. Bill. The drawing is NOT the LEI “Lean Leaper,” which is a trademarked character. This is just his — or her — cousin.

This is why we don't want backsliding? That is dangerous too!

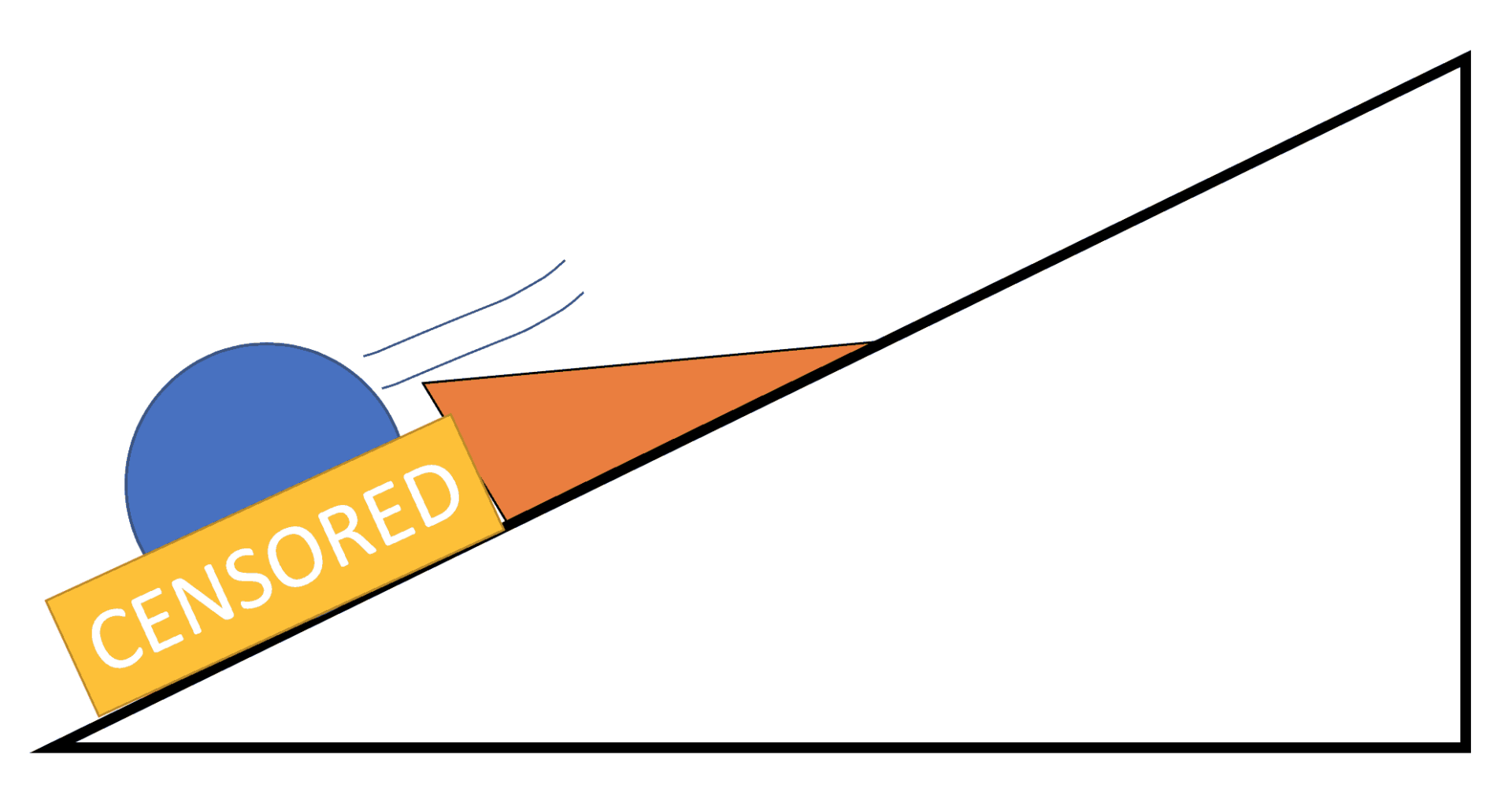

And then we would get this:

Our standardized work metaphor has gotten really grim.

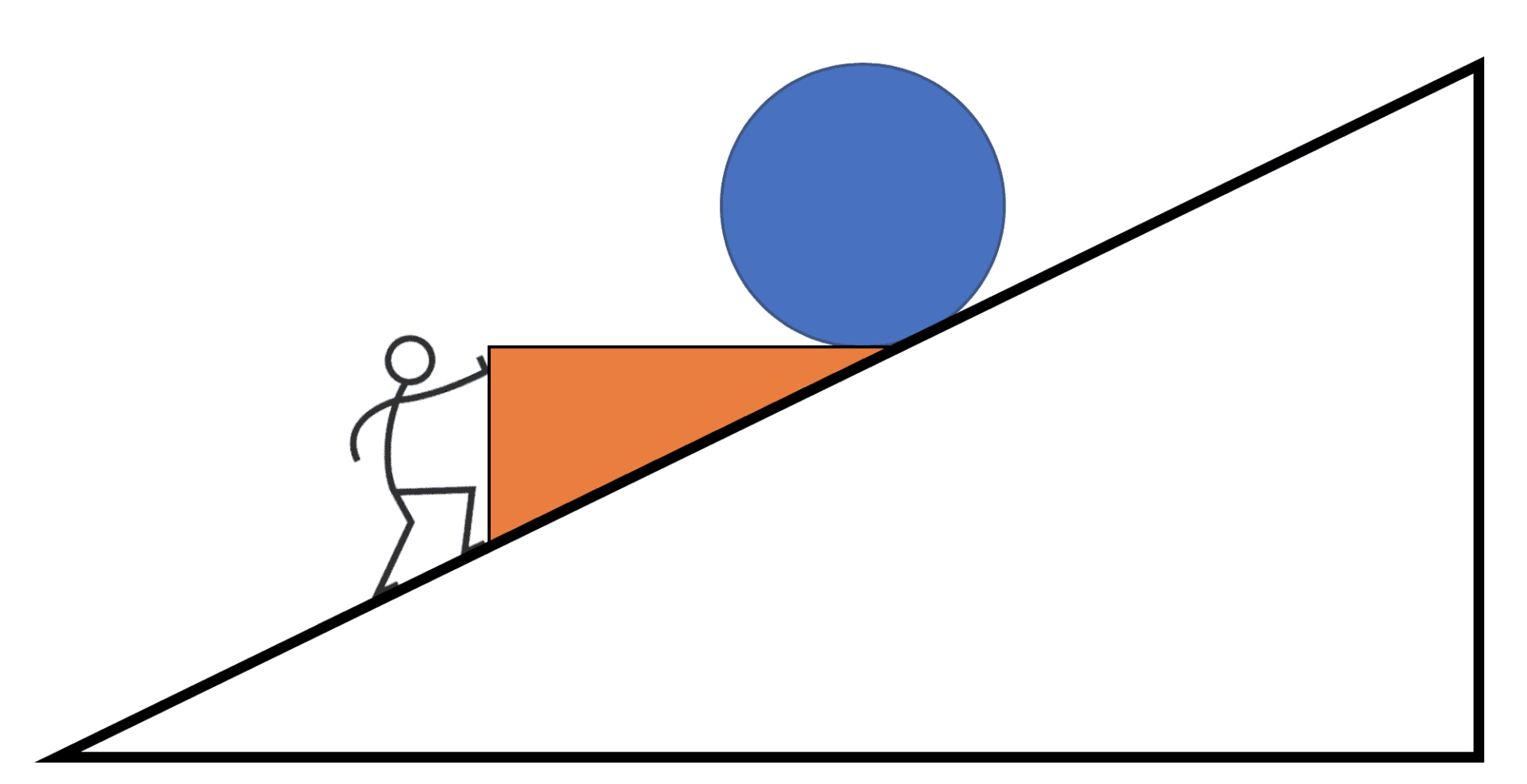

Some illustrations look like the one below… which might seem like less of a death trap:

I'm an engineer, so I'm bound to think about “failure modes” — what about a strong breeze? How low is the coefficient of friction on our wedge?

We know how that story ends (unless the boulder flies over Mr. Lean Leaper).

So, here's the moral to the Lean story:

Backsliding might not hurt us if we duck?

Maybe the wedge needs to have a better shape:

I've seen some drawn like that (Mike Rother's first slide has that version). Maybe that's better. But, perhaps a strong breeze launches it up and over Mr. Leaper? How heavy is the boulder?

I'm with Mike Rother; instead of getting the right wedge, let's retire the wedge… and not just because of the physics involved.

What do you think? Please scroll down (or click) to post a comment. Or please share the post with your thoughts on LinkedIn – and follow me or connect with me there.

Did you like this post? Make sure you don't miss a post or podcast — Subscribe to get notified about posts via email daily or weekly.

Check out my latest book, The Mistakes That Make Us: Cultivating a Culture of Learning and Innovation:

A comment emailed by a Lean friend:

My reply:

Thanks. Yeah, that’s why I tried to make a few somewhat serious points in the beginning of the post, as you’re alluding too.

I agree that we should be working to reduce variation in most cases… but helping people understand why the variation is bad (or why the standardized work can help) is an important part of the equation. I fear that the “wedge” seems very mechanistic and top down…

It is perhaps reflective of a Liberal Arts education but I’ve never been a fan of any of the images above. Always felt uncomfortably close to Sisyphus. The image that I think works better is a basic run chart that shows one level of performance, an improvement, a plateau. It helps to get learners focused on the idea of measurement before and after a change effort and also that improvement happens over time rather being a single event “moving up a mountain” that ends when you get to the top. It helps promote the notion that is an improvement today will seem commonplace tomorrow and new opportunities will arise.

I’ve used the slide that shows what looks more like stair steps but with a slight angle. The horizontal is the standardization and the slight angle the kaizen. I think this helps visualize or reinforce the importance of Standardize Work and Kaizen. Also I have a pet peeve about “standard work” and “standardized work” and “variety” and “fluctuation”. Many people confuse these words.

Salvador — can you say more about your pet peeve there?

Maybe just a nice plateau, created by standard work. It seems addressing the reason why the standard work doesn’t become the default process is a bigger issue. Are we not making the change worthwhile and understandable for the workforce?

This is great take on standard work and I really enjoy the concept of PDSA. It is important to access and improve any situation to try and make it more efficient and to save as much time as possible doing it. In addition to this its important to minimize movement because that’s a waste of valuable time that can be transferred into resources. Standard work helps this because everyone can learn the same process and go through the same training when adapting a new system. It also helps with turnover because anyone can jump in and work at that station so that time is not wasted.

The wedge has always resonated well with me, so reading this and the comments has made me think. I went back and read what Rother wrote on this – “retire the wedge”. What I get from that is, it’s not the wedge itself that bothered him, but putting the word “Standards” in the wedge. He said the Standard actually should come uphill from the rock since that’s our target or aim, adopting the new standard. After thinking about that, that makes sense to me…. But that’s Not how I’ve thought about the wedge — I think about it as techniques like visual reminder cues to help people adopt a new standard, so it’s part of my set of countermeasures to help reach the target, making it easiest to do the right thing consistently. In my experience the most common causes of not adopting a new, truly “better” standard are Forgetting, Not Understanding why it’s better, or Not Knowing how to follow the new standard. Visual cues can help not forget and maybe with the other two reasons if they include a little Why and How to. We have this kind of visual cue in our supply rooms to remind people to follow our 2-bin kanban re-supply process and How to use the cards correctly.

Joe Swartz reminded me of this visual… maybe if the wheel / boulder has enough momentum, it keeps rolling up hill without the need for a wedge. The physics on that isn’t right without some sort of motor or engine involved… but maybe employee involvement in Kaizen is the engine that keeps progressing moving forward… onward and upward.

Here is an illustration shown by a Toyota executive who was speaking in Brazil. It shows a person walking up a staircase. Maybe that’s a better visual than pushing a huge boulder up a hill?

“The way to excellence” is the caption:

Love the article! Sometimes the best standardization isn’t always the easiest one to establish. A great example of how kaizen should be applied to everything to be the most successful!

Guys – seriously you have to be kidding me. You are arguing to retire the wedge and a big part of your argument is “its not Toyota” or “its not Demming” along with a whole series of pages that basically say the same thing. Its as if you think some sacred texts defined what goodness was.

The whole point of continuous improvement is that we use experiments to find out what good is. The only thing that matters about any representation is whether it persuades people to move in a forward direction.

I came to this page to find a better version of the wedge graphic than the one my Toyota colleague gave me to help people grasp why standard work was important. Instead I find a bunch of people who are only interested in following a cult and are arguing about whether something is in the canon of the cult – rather than going out, doing experiments and trying to make improvement.

Seriously – get a grip on reality – because we should be about getting a grip on reality and improving it rather than having religious wars.

Who is having a “religious war”? Cult?

I don’t understand why you didn’t just hit the “back” button if this post was so unhelpful, speaking of “get a grip.”