tl;dr summary: I discuss the persistent quality issues at GM's Livonia Engine Plant from 1996 when I worked there. I reflect on the flawed management strategies, particularly their emphasis on production quantity over quality and the tendency to blame the workforce. This examination includes insights from internal memos, which showcase the management's misguided approach and ineffective problem-solving tactics.

Recently, I blogged about a quality catastrophe that I lived through at GM just over 20 years ago at the now-closed GM Livonia Engine Plant.

Bluntly, the quality problems were caused by poor management and the side effects of their decisions. Even though they constantly blamed workers, management directly interfered with workers and engineers being able to do the right thing for quality.

Here is Part 2 of that story… the first quality “spill” took place in April 1996. As I wrote about last time, Angry high-horse memos were sent out by management. Workers were told to have pride and to pay closer attention to quality (as if those had been the problems).

So, what effect did the memos have?

Another Unfortunate Disruption

In June 1996, we had another major quality issue in our plant.

What happened?

This time, the problem was caused not by defective cylinder heads but by a shortage of engine blocks (one of the areas I worked with as an industrial engineer)… and some engine assembly errors.

We had similar problems and similar root causes… and a similar management response — in the form of angry memos!

I'll excerpt the next two memos that were sent out below, but you can download them as a PDF here.

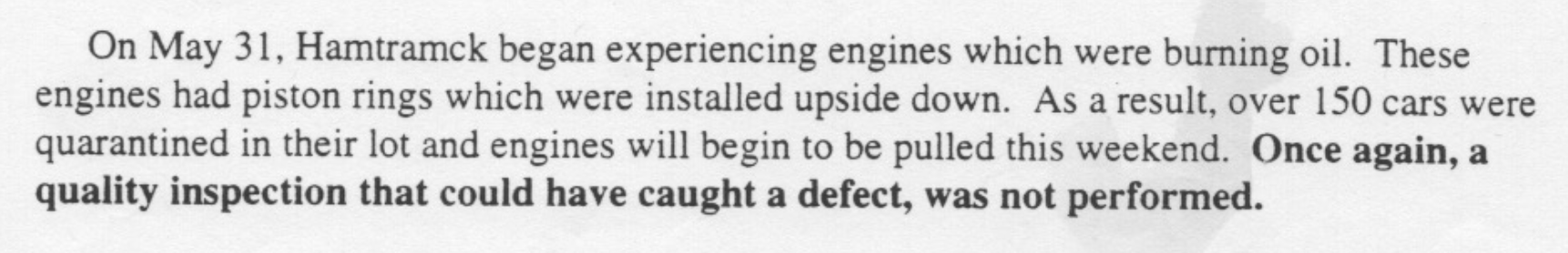

The Plant Superintendent's Memo

Here's the start of the memo from Bob, the plant superintendent (the #2 guy in the plant).

The “quantity first” mindset of the leadership shows in the language they use. They seem more upset about downtime and lost production — ours and the customer's — than they were about poor quality, which is discussed later in the memo.

“The Block line suffered downtime” — this might have been the incident I referred to in the last post where there was a major machine crash because management wouldn't let workers change the cutting tools on the proper schedule.

Or, it was a time when a parts washer (one of the last operations on the block machining line) was down for days.

Either way, the Cadillac car assembly plant was shut down. Why? Because they didn't have engines to put into cars. Why? Because we couldn't build enough engines. Why? Because we couldn't machine enough engine blocks. Why? Because of machine downtime. There are more whys to be asked. Like I said, I forget the root cause of this downtime.

Situations like this created a lot of yelling from management, instead of thoughtful root cause analysis.

So, what happened a week later?

As I mentioned in the last post, management would tell people to cut corners on quality when inventory was low or production quantities were threatened. People were under pressure to work faster.

How do piston rings get installed upside down? Did we have replacement workers on that job who hadn't been properly trained? If so, that's a management problem. Why wasn't the work error proofed? Why was a quality inspection not performed?

If I had to guess, problems occurred because we were playing “catch up” from the week before and quantity trumped quality.

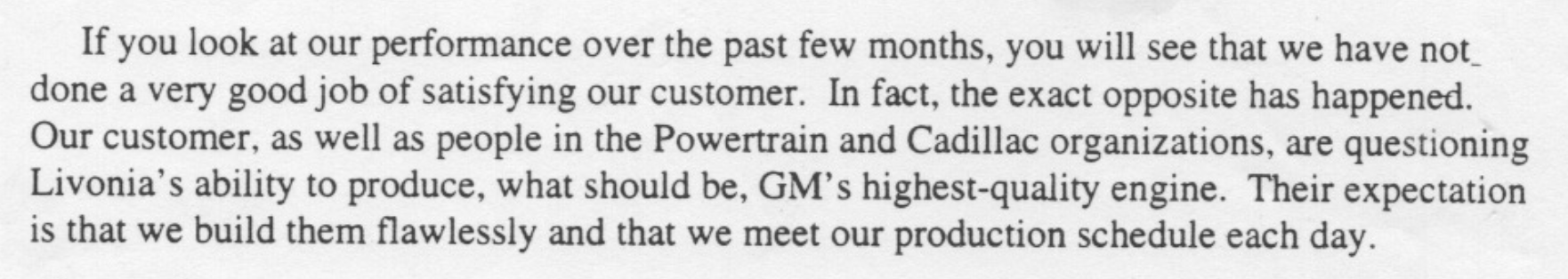

The memo continues as it goes into sanctimonious lecture mode:

“The customer expects the right quality parts, in the right quantity, at the right time.”

Our management team consistently focused on “production schedule” over “flawless” quality. Again, this wasn't the workers' fault.

The guilt tripping continues… which was inappropriate unless Bob was directing the memo at himself:

Pride… trust… all of these ideals were violated consistently by management. It was disappointing to me that our leaders were letting us down, as engineers and production workers (I'd use the more modern term “team members,” but it wasn't really a team environment, unfortunately).

I'm not sure how the April incident didn't wake up management. But, again, they thought the problem was the workers. This theory was disproven by the GM experience with the NUMMI plant that was turned around quickly under a new management system… something that was about to happen at the Livonia Engine Plant under a new NUMMI-trained plant manager.

And the memo draws to a hypocritical close:

It doesn't help when management lectures employees to do the things that management wouldn't let them do.

There's no admission from management that said, “At times in the past, we have wrongly prioritized making this hour's numbers over doing the right thing for tomorrow's quality or downtime. We have failed you as a management team and will resolve to make the right long-term decisions in the future. Please speak up and hold us accountable if we are not doing so.”

And let's end with some more empty words and pep talk stuff:

Memos like this didn't help improve quality or on-time delivery performance. They only increased frustration and cynicism. People reading this memo weren't inspired. They were reminded that management didn't get it.

The Plant Manager's Memo

I don't know if Bob, the superintendent, and Jack, the plant manager, wrote parallel memos in their own attempts to cover their butts. I forget which memo came out first or if they were in our mailboxes at the same time (remember, we didn't have email).

Jack oddly titled his memo “Organizational Focus” as if a “lack of focus” was somehow the root cause (unless, again, this was directed at himself and Bob, who consistently focused on quantity over quality).

He also blames a “lack of attention to detail,” blaming people instead of looking at systems, processes, and culture:

Everybody, try harder!

Care more!

He continues the lecture, which the wording almost suggests is pointed at him in the mirror when he says “we as leaders.”

He's asking the right questions… but again, these questions should all be pointed at leadership at all levels, not just the frontline employees. The memo was addressed to “ALL SALARIED EMPLOYEES” by the way, whereas Bob's memo was addressed to “All Livonia Personnel.”

Jack's message should have applied to everyone, especially when a memo like this would be spread around and commented on by the UAW on the shop floor.

Jack has basically the right sequence… Toyota and Lean organizations state goals in the order of:

Morale isn't necessarily the fifth most important thing… but it was added after the original SQDC priorities became popular.

Jack states these priorities as:

- Safety, Quality, Schedule, Cost, People

I saw many situations in my first year there were leaders weren't doing everything they could to “ensure the safety” of co-workers (as I wrote about here).

Management was often guilty of telling workers to do things that put quality at risk (as I blogged about here).

It's good to see those questions about quality, but they flew in the face of what the daily priorities were. The memo didn't have any reflection or soul-searching about what leadership had done wrong in the past…

- what they had said,

- what they had told people to do, and

- what they wouldn't let people do.

They weren't “providing support to all the people” — they were generally yelling, screaming, blaming, and belittling (as I wrote about here). It wasn't a healthy environment. It wasn't a quality culture.

Under “schedule,” he talked about a sense of “urgency.” Bob used to yell at everybody about not having enough urgency and not working with enough intensity. He apparently thought the problem was people not caring or not trying hard enough. Not at all.

Jack ends with an attempt at a pep talk:

Jack didn't last long as plant manager. Shortly thereafter, Larry Spiegel (one of the original GM leaders who was sent to NUMMI to learn Lean / TPS) was named as the new plant manager of our facility.

Jack was promoted to a role at GM Powertrain headquarters in Pontiac.

And so it goes…

Formative Years

For better or for worse, this is how I started my career.

Did it make me a bit too negative and cynical toward senior leadership when they don't play their proper role in creating a culture of safety and quality? Maybe.

But I learned important lessons (or this was all confirmation bias after reading Dr. Deming's books):

- Quality problems usually aren't the fault of “bad workers”

- Poor quality usually isn't the result of a lack of error or not caring

- Safety and quality DO start at the top. I saw the negative side of that at GM and I also started to see things turn around under Larry's NUMMI-based leadership style.

It frustrates me when I see hospitals today that are more like the “old GM” than they are like a modern, Lean auto plant (which could be Toyota… or GM!).

What are your thoughts, reflections, and comments on what I lived through at GM? Do we see similar thiings happening today in organizations like hospitals or at Tesla?

Please scroll down (or click) to post a comment. Connect with me on LinkedIn.

Let’s work together to build a culture of continuous improvement and psychological safety. If you're a leader looking to create lasting change—not just projects—I help organizations:

- Engage people at all levels in sustainable improvement

- Shift from fear of mistakes to learning from them

- Apply Lean thinking in practical, people-centered ways

Interested in coaching or a keynote talk? Let’s start a conversation.

![When Was the Last Time a Leader Around You Admitted They Were Wrong? [Poll]](https://www.leanblog.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/Lean-Blog-Post-Cover-Image-2025-07-01T212509.843-238x178.jpg)

![When Was the Last Time a Leader Around You Admitted They Were Wrong? [Poll]](https://www.leanblog.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/Lean-Blog-Post-Cover-Image-2025-07-01T212509.843-100x75.jpg)

I like your words: “But I learned important lessons (or this was all confirmation bias after reading Dr. Deming’s books).” It’s not confirmation bias. People just want to be respected. This is a prerequisite to doing good work. It is a reality that leaders ignore to satisfy their own interests.

I also like: “The memo didn’t have any reflection or soul-searching about what leadership had done wrong in the past…” They almost never do. It is another way to separate the identities of management and labor. These features of organizational life are rooted in a long-ago past that continues to serve the interests of leaders. Hence, no change.

Thanks for the comment, Bob.

No change. I’ve decided it’s a fool’s errand to try to change people.

It’s like the old joke about how many psychologists does it take to change a light bulb? One, but first the light bulb has to want to change.

I don’t think most hospitals have a chance at high-minded high-reaching “Lean transformation” with existing leaders in place. Most hospital executives seem to be more like the GM people I suffered under 20+ years ago than they seem like humble Toyota servant leaders. Elon Musk reminds me more of those GM leaders (including the former GM CEO Roger Smith who shared pipe dreams about lights-out factories).

Our GM plant only began changing when we got a new plant manager. It’s really difficult for a hospital CEO who has been in place for 10+ years to lead any sort of internal revolution in terms of culture and management mindsets. At one point is new leadership needed to have a fighting chance?

Hi Mark,

Yes, it’s a fool’s errand to try to change people; particularly on an individual basis. Most interestingly, people – both individually and collectively – are capable of changing in ways that are both beneficial to themselves and to the organization/institution of which they are a member. The key is take a page out of Drucker’s playbook in terms of what he has stated about trying to change an organization’s culture… “it’s akin to pushing on a string.” Instead of attempting to change individuals and/or culture directly, Drucker (1993) has suggested “… one of the most important challenges for any organization is to build SYSTEMIC practices for managing a SELF-TRANSFORMATION.”

That said, what tends to be a much, much more effective approach is for Senior-level Management team members to take on as their PRIMARY RESPONSIBILITY… creating and evolving and sustaining a work ENVIRONMENT which is most conducive to each and every member of the organization engaging their fullest discretionary THINKING AND BEHAVING in the pursuit of a clear and truly COMPELLING TRUE NORTH ORIENTATION (i.e., the combination of a value-oriented MISSION/PRIMARY PURPOSE, the desired/targeted FUTURE-STATE VISION, ENDURING VALUES, and the near and longer-term OBJECTIVES).

Such an ENVIRONMENT is a key influencing element in overall composition/make-up of an enterprise/business/institution as a holistic SYSTEM. Just as is the case for rotting fish, the process begins with fish’s head, so too is the case with a man-made business SYSTEM… If it’s guiding/governing direction/orientation is NOT something the members of that SYSTEM can/will fully buy into, then it does not matter how much emphasis and effort is placed on making improvements. At best, efforts being made in the CONTEXT of a non-inspiring, non-supportive/enabling, non-committed ENVIRONMENT will be little more than palliative in nature.

Indeed; trying to change people (incumbent leaders) has proven to be ineffective. Then, with new leaders, we soon we run into the problem of changes in leaders and changes in ownership, which quickly reverses any progress that has been made in both people and processes. It seems to me the Lean movement is at a crossroads. Deny these problems exist (as in JPWs “Rethinking the Model Line” post earlier today) or bring people together (friends and enemies) and try to figure out what to do, as no one person has the answers to this incredibly vexing problem.

I think it is possible to change people but they need to understand that they have an option to behave differently and understand what outcome that will bring. The practice of engaging them in that way that I’ve found most effective (and I’m still learning and practicing every day) is Humble Inquiry.

HI Mark,

As I read this, I couldn’t help but thinking of 2 recent examples of attitude delivery from above during tough situations. One in the retail coffee industry and one in the airline business (not sure about that one). I am ecstatic to see such ownership of problems from the very top, with dramatic, large scale CAPA to boot. Closing 8,000 stores to re-train? That’s big.The only question I have for them is “why was the original training not effective?”

In the past, I recall seeing responses from other CEOs that had a different tone. Politicians, tobacco, energy, etc. deflecting and often blaming the worker.

Hopefully recent efforts to be more transparent and accountable will set the precedent for the future.

Also, you showed some examples of the memos written the “wrong” way, but could you share some examples of some “proper” memos, aside from Jack’s one, which added the questions to ask oneself?

Keep up the wonderful articles!

Jonathan – thanks for your comment. Yes, when “retraining” is proposed as a countermeasure, I also like to ask that same question about why the initial training wasn’t effective.

It’s unclear if Starbucks has done training like this before or if it’s the first time.

How would they know if the training is successful? Why not do a small test of change with a handful of stores before rolling out to all 8,000?

I guess they must have a very strong hypothesis (and definition) of success… or they need to make a big showy public statement that may or may not be effective.

To the question about memos… I’m not sure if management by memo is really ever that effective, even if the memo is “right” in tone, audience, and content.