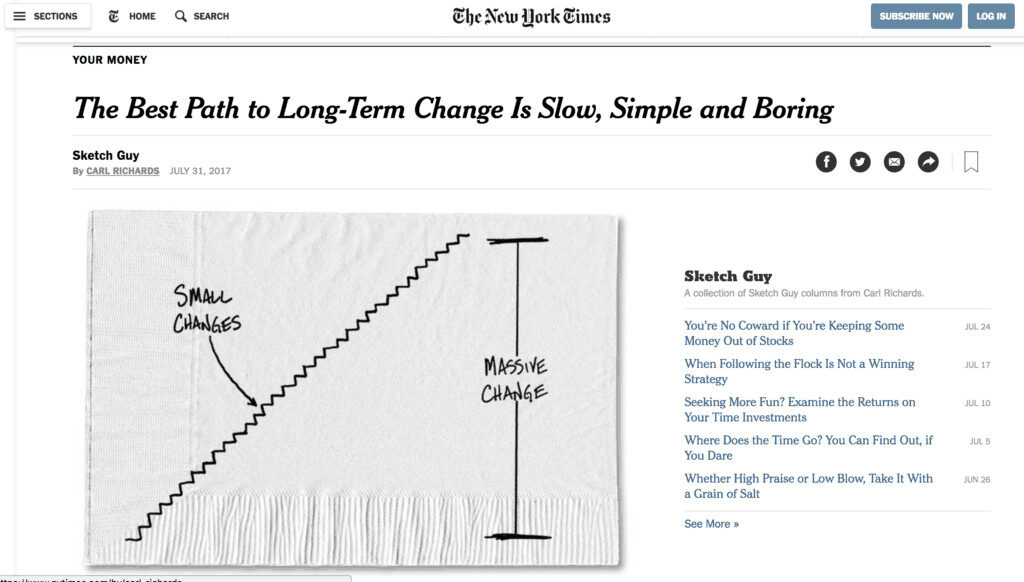

I am always happy to see something even vaguely related to the practice of Kaizen in mainstream publications. Here's a recent essay from the New York Times:

The Best Path to Long-Term Change Is Slow, Simple and Boring

The author, Carl Richards, asks why the “exciting and complex and quick” solution that “rarely works” (such as weight loss pills or day trading) – what he calls “Option A” – are so much more popular than a “boring and simple and slow” approach that “works nearly all the time” – “Option B.”

Richards isn't really that puzzled, as he wrote:

“There are plenty of reasons we pick Option A over Option B. It's got me thinking about the quiet power of incremental change. Incremental change is about taking small, gradual steps instead of making big sweeping changes.”

It's not that puzzling to me. People love the silver bullet, easy peasy quick fix. Dr. Deming warned against “instant pudding.”

Jim Womack has liked to frequently say something like:

“People will try anything easy that doesn't work before they'll try something hard that DOES work.”

Hospitals will keep trying layoffs and slash-and-burn cost cutting. That's easy. Does that really work?

Lean and Kaizen are the slow and boring alternative… it takes longer, but it seems more likely to work, as this now-retired hospital CEO figured out:

Last week, at the Studer Group What's Right in Healthcare conference, Isaac Lidsky made a very similar point about incremental progress, as I tweeted:

"You will not get from A to Z if you don't get first from A to B." @isaaclidsky #WRHIC2017

— Mark Graban (@MarkGraban) August 3, 2017

Lidsky was a fascinating speaker by the way… a child TV star who graduated from Harvard at 19, clerked for two Supreme Court justices… and then went blind. He's author of the book Eyes Wide Open: Overcoming Obstacles and Recognizing Opportunities in a World That Can't See Clearly.

If an organization wants to go from the 10th percentile in patient satisfaction to the 95% percentile, there probably isn't one big huge improvement or project that will get you there.

It seems more likely that there's dozens of improvements and changes.

We can continuously improve what we already have (Kaizen) or more radically redesign things (“Kaikaku“).

Richards continues to sing the praises of Option B:

“You know what will work? Small actions repeated consistently over a very long period of time. Incremental change is short-term boring, but long-term exciting.”

Richards talks about the need to track progress:

“…keeping track of this incremental change helps reinforce why I'm making short-term boring choices. Because at some point, I'll look back and see how far I have come, and short-term boring will become long-term exciting.”

If you're improving patient satisfaction or HCAHPS from the 10th percentile to the 20th… and then to the 25th and then the 35th, you might see there's still a big gap for potential improvement.

Hopefully seeing that progress can keep you on that path of incremental, sustainable improvement.

Another thought… is the path to improvement the simple stair steps that Richards wrote… or is it a winding path, like you see here?

Gain knowledge to help your organization along the lean journey. Join us at a Lean Leadership Series near you: https://t.co/Vs0wvTDeGJ pic.twitter.com/juldYS9W2A

— Catalysis (@HCValue) August 7, 2017

What do you think?

Please scroll down (or click) to post a comment. Connect with me on LinkedIn.

Let’s work together to build a culture of continuous improvement and psychological safety. If you're a leader looking to create lasting change—not just projects—I help organizations:

- Engage people at all levels in sustainable improvement

- Shift from fear of mistakes to learning from them

- Apply Lean thinking in practical, people-centered ways

Interested in coaching or a keynote talk? Let’s start a conversation.

![When Was the Last Time a Leader Around You Admitted They Were Wrong? [Poll]](https://www.leanblog.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/Lean-Blog-Post-Cover-Image-2025-07-01T212509.843-100x75.jpg)

The “Success Arrow” shows the real story for sure. As we’ve discussed, implementing and sustaining Lean is simply hard work. The variables within a culture are such that change is the significant constraint in a “I want it now” society. It just doesn’t work like that . We’ve had some huge wins, amazing growth and now a new set of challenges. With approximately 40% of our organization being here less than 2 yrs the hiring and on-boarding to what many believed was a strong lean culture has been real ugly at times. Yet as your blog nails the reality, it is those simple, consistent small steps of positive change that truly transform the culture that creates a foundation to keep improving. A very relevant subject in our times. Thanks for sharing.

People are like electricity and water, always looking for the path of least resistance.

To me, its more like this http://www.mcescher.com/gallery/recognition-success/ascending-and-descending/

Discussion from Linkedin:

Peter Thweatt:

Thanks for reiterating these points. I believe people often forget the purpose of Lean and other process improvement techniques is to not only increase efficiency but to increase sustainability as well. There is no short term fix for the later. I believe it’s only “boring” in the sense that it becomes part of the everyday workflow. In my mind, that’s actually a good thing, something we should be excited about. Thanks again for posting.

Andre DeMerchant:

Mark Graban…great blog post today, very key points well worth repeating! As a consultant ‘in the wild’, I often have to deal with clients looking for that magical, one shot solution needed to bridge a gap when what they SHOULD be doing is figuring out how to construct the bridge piece by piece. Human nature is such that we, of course, always want to be able to hit the ‘easy’ button on everything…..and dedication to small-step, repeatable improvement isn’t part of that. You know the old saying: ‘hard work eventually pays off, but laziness pays off immediately’. I fear that in a society that is becoming more and more focus and attention challenged, our inability to stick to step-by-step incremental improvement is an issue that will get worse before it gets better. Please keep reminding us!

As much as I agree in principle re the value of sustained incremental improvement, many organizations (for a variety of different reasons) don’t have the luxury of a long runway. I’ve worked with organizations that had the same staffing levels as they did ten years prior despite the fact that their customer base had been cut in half in that same timeframe. When you compound that with the fact that Parkinsons Law kicked in during the interim as employees created NVA work to fill the time not occupied by service delivery, you have organization that can’t possibly get cost-competitive quickly enough on incremental improvements alone.

We can say “woulda, coulda, shoulda” re their decade-long leadership decisions all we want, but that won’t change the fact that we have an organization with bad processes, AND labor costs that were 50% higher than their competitors, AND losing thousands of customers per month, AND operating in an intensely competitive market. Patience isn’t a viable strategy in that scenario.

I would love to work with organizations that genuinely have the luxury of time, but that’s rarely the case. There are no easy solutions and that’s the reality many of us have to deal with every single day.

Thanks for your comment, Robert. It’s quite possible that small steps might be the best path to results (better results, more sustainable results) but it’s not the FASTEST path.

I was talking the other day with someone who was laid off as the P.I. director for a hospital. He was pretty blindsided by it. We were chatting about the conundrum of:

1) There’s pressure for ROI and quick results

2) But the projects and methods geared for ROI and quick results don’t last without the slower changes (to the management system and culture)

I don’t know how much of the layoff / downsizing of him and his team was due to “not getting results” or “not getting the right results” or “not getting results fast enough.”

In your scenario, as much as I’d say “don’t use Lean for layoffs,” that sounds like a scenario where a 50% one-time layoff might be necessary and might truly be a matter of survival for the organization. That’s different than laying off people to, for example, maintain a 4% margin instead of it dropping to 2%.

Many of these healthcare layoffs don’t seem to be cases of organizational life or death.