When I hear the word “project,” I think of long team-based initiatives that last for weeks or months.

1. something that is contemplated, devised, or planned; plan; scheme.

2. a large or major undertaking, especially one involving considerable money, personnel, and equipment.

Miriam-Webster doesn't necessarily define it as “large or major,” but I think that's the implication in most organizations.

1: a specific plan or design

3: a planned undertaking: such as

a : a definitely formulated piece of research

b : a large usually government-supported undertaking

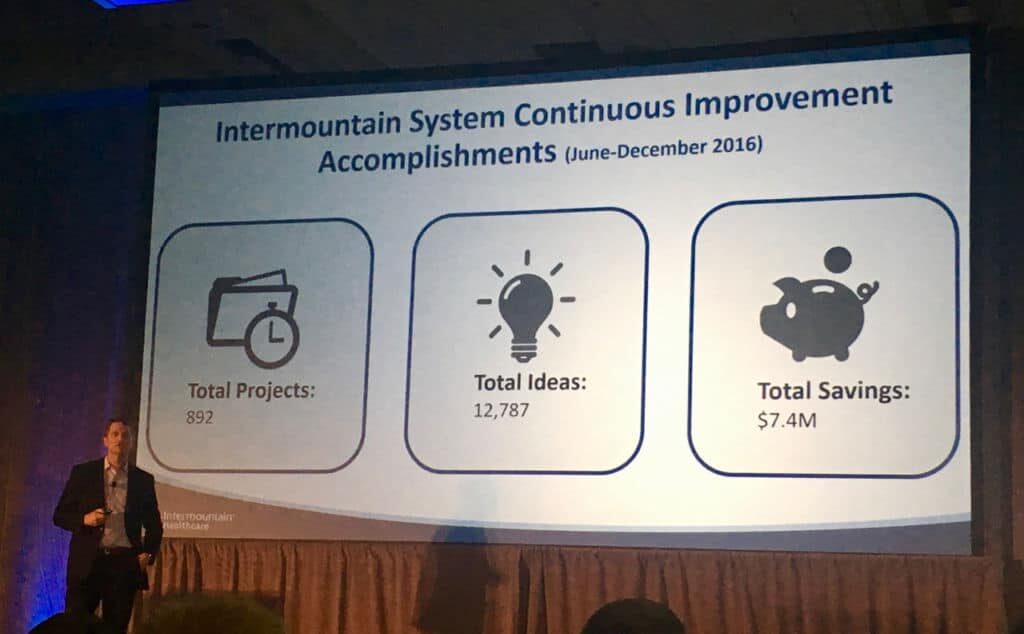

Last week, I shared (on Twitter and in this blog post) this slide from the presentation given by Tim Pehrson who is CEO of North Region (five hospitals) & VP of Continuous Improvement for Intermountain Healthcare.

There always some risk when you share snippets from a presentation. As Donald J. Wheeler, PhD says, data without context have no meaning.

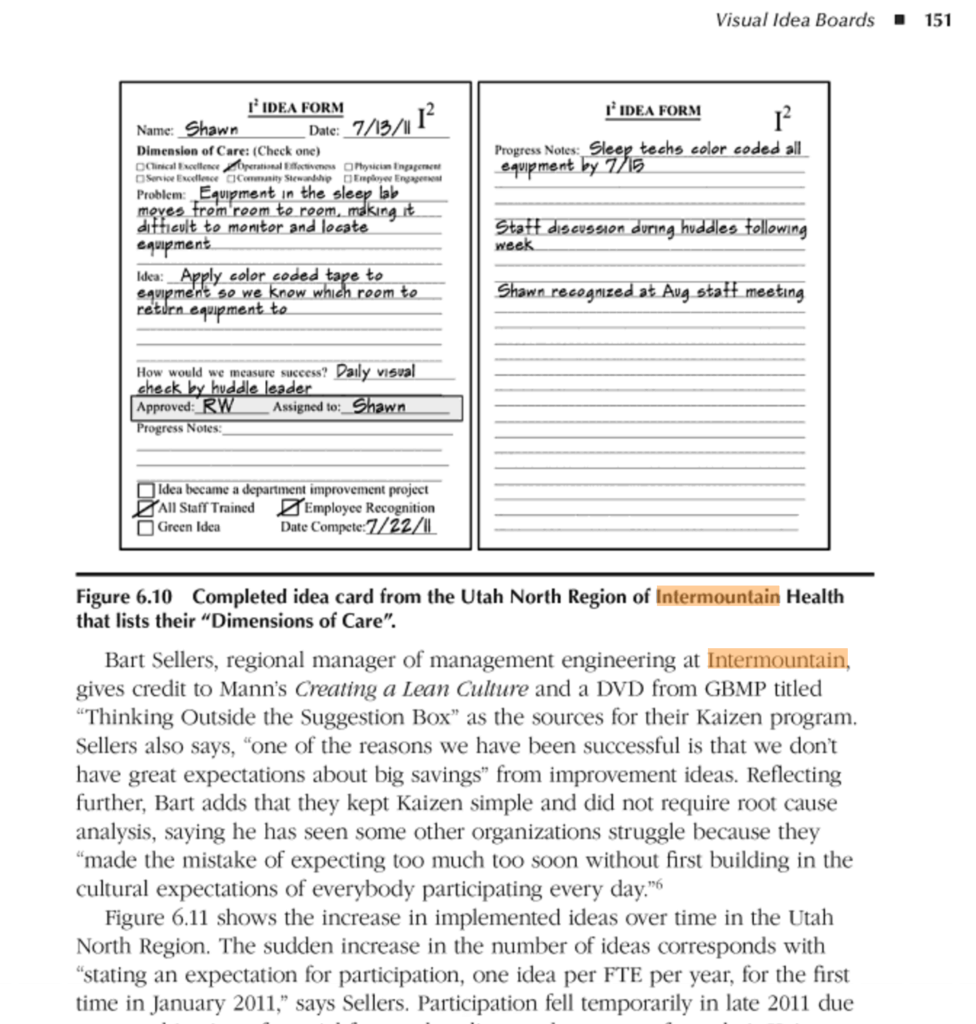

My best attempt at sharing context is that Intermountain first embraced continuous improvement within the North Region. I first had a chance to visit McKay-Dee Hospital, which is part of that region, somewhere between 2008 and 2010 or so. There are a few references to Intermountain in our book Healthcare Kaizen, as a result of the few visits I've made there:

That “idea card” is a classic example of what's used to facilitate small Kaizen… the types of improvements that are too small to be labeled “projects.”

In Tim's slide above, the data there is for the entire Intermountain system. They are still in the process of rolling out the continuous improvement process from the North Region to the entire system.

12,787 ideas means implemented ideas, not just idle suggestions that didn't go anywhere. These are actual changes… improvements.

In addition, 892 projects means some of those were larger ideas with more involved work.

The $7.4 million in cost savings wasn't the only measure that mattered to them. Cost savings is often the easiest measure to add up….

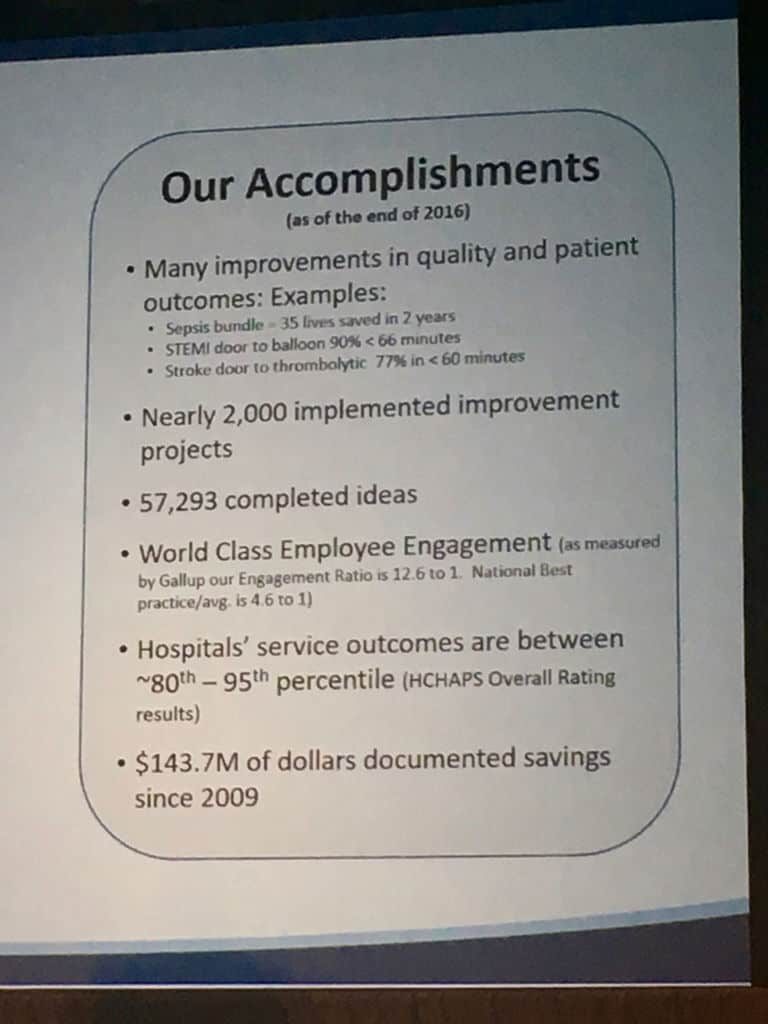

But if we look at another slide Tim showed, here are the results from the continuous improvement work in the North Region over previous years:

They're looking to improve quality and safety, service to patients, and employee engagement. It all goes hand in hand. It all leads to cost savings, as an end result, which is different than doing “cost cutting.”

Notice the ratio of projects (bigger changes) to ideas (small changes) is about the same:

- 892 / 12787 = 6.9%

- 2000 / 57293 = 3.4%

Not everything has to be a “project.” I have one client who is trying to break a habit of referring to improvements as “projects.” Their default was long TQM-style projects. They are trying to switch to a Kaizen model of continuous improvement, where 80% of improvements are “quick and easy,” as Norm Bodek would call it. But, for a while, they were still calling the small stuff “projects.” They're getting better at this.

The term “project” tends to scare people off a bit. They think a project means a lot of work and that they don't have time for a project.

When I posted the first slide on LinkedIn, the comments there reflect some of the biases people have about improvement.

A person with a Six Sigma background commented:

“Interesting topic, it seems that the Healthcare sector is SO ripe for improvements, there is opportunity in every direction. The average save comes out to be ~8,300 per project seems very low. I just think that the results of an effort in this space would yield much greater financial results.”

He had done the math of 892

I might have been a bit snippy in my reply, but I asked:

- Why do you think this is all about projects?

- Why do you think this is all about cost savings?

There's another common bias that says you HAVE to set targets or goals for improvement. I've found that the thing that really matters is the behavior of leaders. If they do the things that encourage participation and improvement, then you'll see improvement that's very self-motivated. Goals and targets can get dysfunctional.

The commenter wrote:

“As a data driven person I see the value in tracking ideas. The quandary I have is whether to set goals or just track and try to improve. I have seen world class automotive companies set goals and work hard to achieve them yet others say shouldn't set goals for ideas just encourage them.”

I'm in the “just encourage them” camp (and that would include coaching, facilitating, recognizing, and other behaviors).

There's also another assumption or bias (or experience shows) that a large number of “ideas” don't lead to any improvement.

A commenter wrote:

“If ideas create projects and projects create savings then basically they are turning 7% of the ideas into projects that are worth about $8,296 per project. that would seem to have a couple consequences. just under 12,000 of the ideas didn't get any action which can cause some moral issues if people feel they are being ignored. At $8300 per project if there is any cost at all the net savings is at best 50% of that number.

The point is that big numbers trigger emotional responses but they don't necessarily make business sense. This program could very easily be running at a loss and people will run around all jacked up over these numbers and then wonder why management shuts it down. Out of 12 thousand projects nobody had the insight to put enough money on the table to keep management interested. It looks like the people doing projects are doing their part. The people managing the program seem to off target.

For one, there's a bias that says management only cares about money and cost savings. I don't think that's the case here.

The commenter had misinterpreted the slide and the numbers. The difference between projects and ideas is in scale/size. They were all implemented projects or ideas. The commenter mistook 892 / 12787 to be an implementation rate, which would have only been 6.7%… which would be more like a suggestion box than a Kaizen system.

6.7% would actually be a HIGH implementation rate for a suggestion box system.

What we see in an effective Kaizen system is closer to 90% implementation rates. Again, that slide that Tim showed had numbers for implemented ideas and projects.

Someone else wrote that the cost savings number doesn't look that big in context of the organization's revenue:

“Considering that this is a $7 bn /year organisation, $7 million saving being discussed, is just 0.1%… seems they still have tremendous potential for improvements…which they need to tap.”

I think that's fair. Tim was presenting about STARTING to spread this methodology throughout Intermountain. They'd probably agree there is still tremendous potential.

I think every health system has this sort of potential. I applaud Intermountain and others who are making progress in this direction. What about your organization? What about your local health system, if you're a patient?

Please scroll down (or click) to post a comment. Connect with me on LinkedIn.

Let’s work together to build a culture of continuous improvement and psychological safety. If you're a leader looking to create lasting change—not just projects—I help organizations:

- Engage people at all levels in sustainable improvement

- Shift from fear of mistakes to learning from them

- Apply Lean thinking in practical, people-centered ways

Interested in coaching or a keynote talk? Let’s start a conversation.

![When Was the Last Time a Leader Around You Admitted They Were Wrong? [Poll]](https://www.leanblog.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/Lean-Blog-Post-Cover-Image-2025-07-01T212509.843-238x178.jpg)

![When Was the Last Time a Leader Around You Admitted They Were Wrong? [Poll]](https://www.leanblog.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/Lean-Blog-Post-Cover-Image-2025-07-01T212509.843-100x75.jpg)

Mark, very interesting analysis of data presentation. I live in Poland and work in the hospital long time. I am developing management systems based on ISO norms. Though more than 10 years I see many changes but it still need time for medical environment to understand the power of different improvement tools. Physicists also need time to convince themselves to learn from other sectors, like automotive one. But I believe, that one day we will find enough strength to start with lean and kaizen as VMMC and will find our own tremendous potential as Intermountain. Thank you.

Mark, I agree with the basic premise that not every improvement idea is a project. I am starting to believe that all this “bean counting” is a way for weak leadership to justify “the right thing to do.” These dollar savings are often swags based on the organizational standard used to capture cost avoidance. No one has done any recent analysis to prove these measurement systems are still accurate from when they were first put into place. If the management team agrees that an improvement is the right thing to do, why do we need to fill out an ROI form that usually is not accurate anyway?

Thanks for your comment, Scott. Great point. I agree that a culture of continuous improvement is a “must have” for an organization. Look at the cost of not having that culture… oh wait, that’s hard to measure.

I would be totally comfortable running an organization that did not require an “ROI” or “cost savings” from improvement activity. We should just be managing the business and the real bottom line, right?

And, of course, I would definitely not require every improvement activity or project deliver a specific ROI. That’s a dysfunction I hear about with many Six Sigma initiatives (such as “all black belt projects must deliver $X in cost savings”). Not everything that matters can be put into dollar terms.

One thing Tim talked about was the need to reach today’s executives with their existing mindsets. Is it a necessary evil to talk about ROI and cost reduction to get their attention and, for better or for worse, earn the right to do improvement? I know it shouldn’t be that way… but is talking about ROI a necessary step… or does it keep today’s executives stuck in the same thinking… does ROI talk prevent them from moving their thinking forward to something better? I think that’s a great risk…

And here’s the discussion from LinkedIn on this post.

We seem most often to get stuck with definitions e.g. project versus idea. The variation in how people define these terms makes it difficult to compare their “calculations.”

I also don’t understand what value such arbitrary distinctions provide management. How does it guide their decisions? I see natural subgroups in categories like 1] number of improvements at individual level i.e. work a single person does, 2] at a single value-stream level, and 3] at the system level i.e. dealing with multiple value streams coming together. This type of sub-grouping allows insight into the performance of different levels of hierarchy within the system, no? Perhaps this type of data is difficult to collect?

Cheers,

Shrikant Kalegaonkar

I don’t think the distinction is meaningless.

Now, the distinction might be a bit arbitrary and there’s grey area. Is it a “project” if four team members work on an improvement for five hours? I dunno.

I think the distinction can help guide which improvement method is used (although, again, there’s grey area). When is a problem complicated enough to require an A3? When is it a “just do it?” When do we need to formally charter and get approval for a large project?

I think that’s worth figuring out as an organization.

In healthcare workplaces, I see very few improvements that are purely a solo activity…

What’s the cost of doing the “accounting” for improvement work? Is it necessary or a situation where we should do “cost / benefit” analysis of tracking the benefits?

When I hear the word “improvement,” I think of getting better. However, many colored belts I’ve talked to or work/worked with automatically think improvements=projects. I guess this is another fallacy with colored belts. What I think is most important in any type of improvement is the behaviors of leaders. Encouraging participation and engagement in improvements, whatever their size is. This requires leaders to take a hard look at themselves and make the necessary changes. This naturally leads me to think of Dr.Toussaint’s recent article “Five Changes Great Leaders Make to Develop an Improvement Culture.”

Thanks for the comment, Sam. I think the “belts” are trained to think of improvement as projects… and usually it’s projects with “ROI.”

Do those “belts” get a chance to influence the leaders? Probably not, especially if the leaders just want ROI delivered to them through projects that that keep at an arm’s length distance.

Do the leaders get training in Lean Six Sigma? At Honeywell, there was a “Six Sigma for Leaders” class that some (not me) cynically called “Six Sigma for Dummies” because it was pretty superficial. Did that training change their behavior or the culture? Probably not.

Looking in the mirror and realizing change starts with you is difficult… and it’s a hard sale to make in an industry.

“Change starts with me? Nah, just fix my inefficient employees who are wasting money.”

That’s not a path to improvement, transformation, or business success.