I was honored to have an opportunity to present with my friend Chip Ponsford, DVM at the Veterinary Leadership Conference that was held this month by the American Veterinary Medical Association. Check out Chip's blog and

Here is the description of our talk from the program:

About a week before the conference, Chip was the lead presenter for a webinar on the broader Lean methodology and its applications in vet med practices. At the conference, Chip teed things up (talking about “the why” — why is this important for vets and practices), and then I was the lead presenter about the “Kaizen” approach to continuous improvement.

During the session, I shared some Kaizen examples from a large animal hospital setting (a place where I once spent a week as a coach), and Chip shared his own examples from small practice settings.

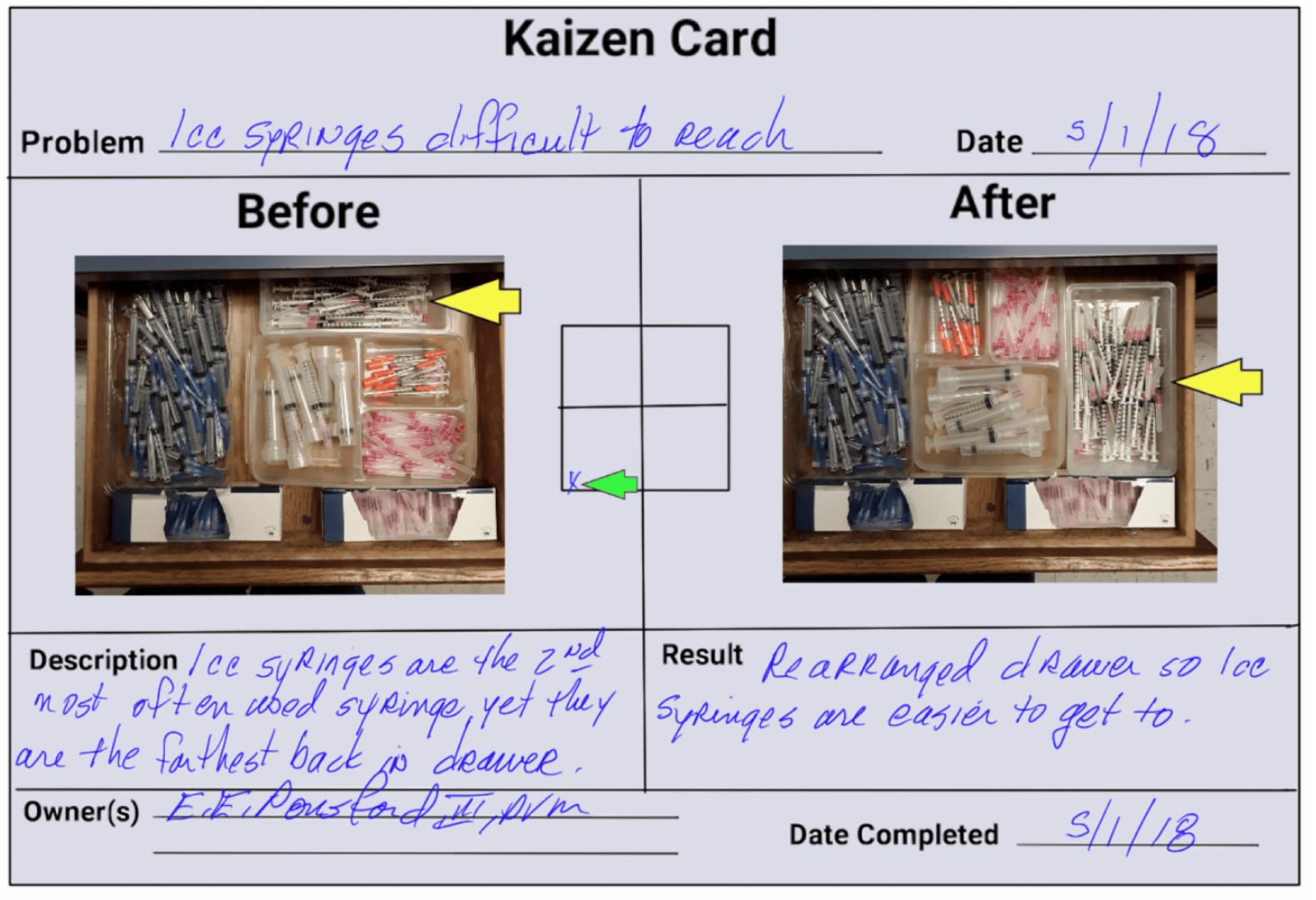

One example of an improvement that Chip implemented was as simple as making syringes easier to find in a drawer, as documented here:

We shared examples like that to emphasize Kaizen principles like:

- Start with small problems and small improvements

- Engage the people who do the work (in this case, Chip as a vet)

- Make work easier and less frustrating

We emphasized small, low-cost, low-risk improvements as a way to get started. There's a time and place for projects and bigger, more systemic improvement efforts, but you have to start somewhere.

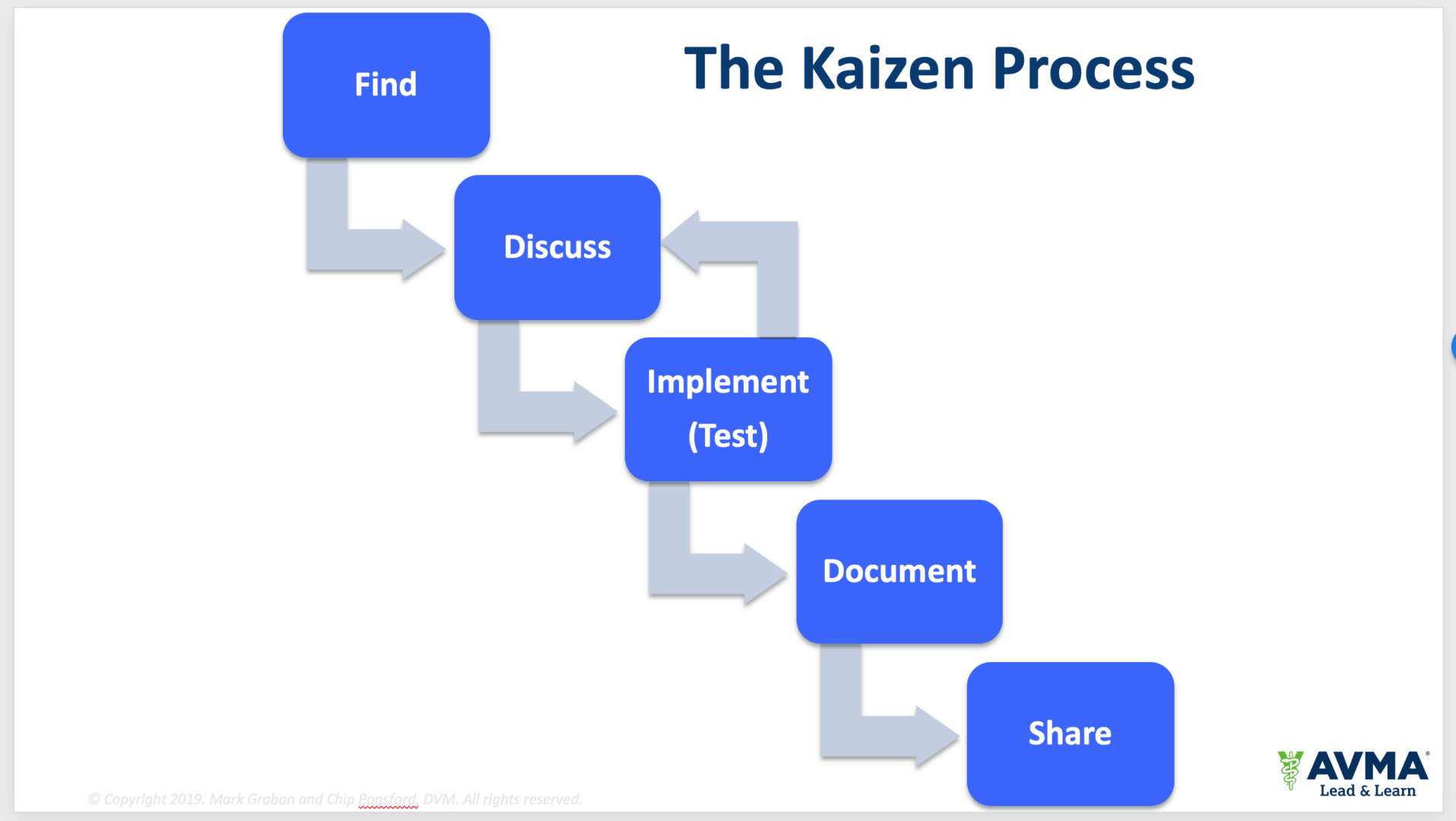

I shared the Kaizen model that Joe Swartz and I shared in our book Healthcare Kaizen (which is admittedly aimed at “human healthcare” settings even though the principles are universal).

Discussing problems, opportunities, ideas, or solutions is the second step of this process. Employees are engaged and empowered, but their managers and leaders should be coaches and facilitators — partners in improvement. Leaders are responsible for “the system” but they don't have all of the answers. Employees have an important role in raising issues and brainstorming and testing solutions.

The first two questions (one during the talk and one at the end) were basically the same. I'll paraphrase:

“What if an employee implements something really dumb without my permission?”

In my experience, that's not likely to happen. If anything, employees are more likely to be cautious if not scared.

It's more likely that employees will go to their manager for permission… even for small, non-controversial, low-risk, easy-to-test-and-possibly-undo changes.

Leaders, if anything, draw boundaries around “here's the types of changes you can test without permission” — things like Chip's desk drawer improvement.

If leaders are really that scared of their employees and their judgment, maybe they've hired the wrong people (and whose responsibility is that?).

If “really dumb” (in the words of a manager) means “something that didn't work,” then maybe leaders need to reframe that “failure” as “learning.” You don't want people trying any irresponsible thing… people need to have a reasonable hypothesis… “if we do this, then that will happen.” But, sometimes you'll get results that are different than you predicted. That's an inevitable part of the improvement process. It leaders want “guaranteed success,” then people will be afraid to try to improve.

If “really dumb” means “dangerous” or “illegal” — I'd be really surprised if that happens, actually. Even if a really dumb idea comes up, it's likely to be caught if we're discussing improvements within a team. A really dumb idea is most often the starting point for finding a better idea (and we're driven to do so because there's likely a problem to be solved).

If “really dumb” means “that won't work,” that should be the starting point for our discussion that's aimed at coming up with something that seems better.

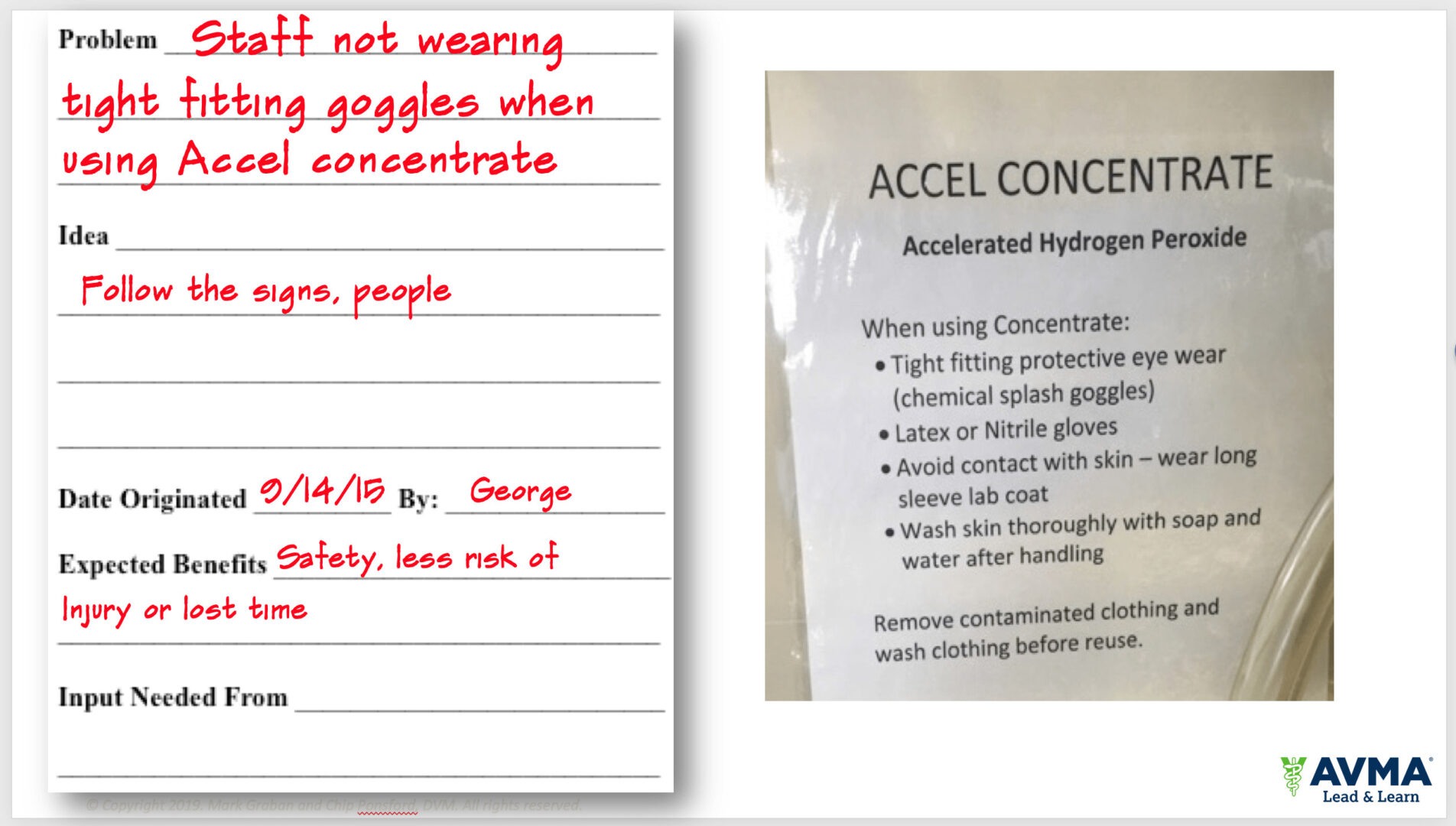

Was this a dumb idea to say, “Follow the signs, people?”

Instead of throwing out that card or “rejecting” the idea, start a conversation about what can be done to resolve this situation.

Even with those skeptical questions (that I've heard before in other settings), I think the room was energized by the idea of Lean and continuous improvement based on the other questions, comments, and follow-up discussions.

Consistent Themes on Culture Change

I was only able to attend a few other talks, but there were many ideas and themes that were consistent with Lean and Kaizen. Two veterinarians talked about making the most of your improvement ideas and there were many parallels to Kaizen, even though they used different terminology.

Another session (presented by people from this group) immediately before ours talked about “next-stage practice management.” There were many ideas and themes that were consistent with Lean and Kaizen.

That talk's main themes included shifting:

- From “predict and plan” to “experiment and adapt” (with the foundation of a long-term vision… which reminds me of “The Lean Startup” approach)

- From “hierarchical pyramid structure” to a “network of teams”

- From “directive leadership and centralized authority” to “collective leadership and distributed authority”

- From “a focus purely on profit” to “purpose and values”

- From “secrecy to radical transparency”

- From “dependence on extrinsic motivators” to “unleashing intrinsic motivation”

That last point… another common question leaders ask is about extrinsic rewards for continuous improvement efforts. We can accomplish more by tapping into intrinsic motivation (check out previous posts and this podcast with Dan Pink).

Many organizations want to “implement Lean” (which implies a “predict and plan” model) or they cherry-pick a few Lean tools that sound good (instead of embracing Lean as a holistic and experiment-based system).

There are lots of startups. A large percentage of them might think they can become a so-called “unicorn” startup with a billion dollar valuation. But, the odds of this happening are really low. That doesn't mean we shouldn't try, right?

Are there parallels to Lean in organizations?

What do you think about any of this? Do you fear that people will do really dumb things in the practice of Kaizen or Lean? Have you gotten over that fear? What have you experienced?

Please scroll down (or click) to post a comment. Connect with me on LinkedIn.

Let’s work together to build a culture of continuous improvement and psychological safety. If you're a leader looking to create lasting change—not just projects—I help organizations:

- Engage people at all levels in sustainable improvement

- Shift from fear of mistakes to learning from them

- Apply Lean thinking in practical, people-centered ways

Interested in coaching or a keynote talk? Let’s start a conversation.

![What’s Your Organization’s Real Mistake Policy? [Poll]](https://www.leanblog.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/Lean-Blog-Post-Cover-Image-2025-07-17T085114.134-100x75.jpg)

Discussion on LinkedIn:

I think I’ve said this before, maybe on FB, but I approve of the pugicorn photo.