Check out Part 1 and Part 2 in this series.

As I was blogging about before, Toyota has been deeply influenced by “Total Quality Management” and that's still terminology that they use and teach today.

I had a chance recently to revisit Steve Spear's classic HBR article on Decoding the DNA of the Toyota Production System.

In the intro, he and Kent Bowen wrote:

I'm not sure many American organizations are widely introducing “quality circles” as part of their “Lean journey” these days. I'm more likely to see kanban cards being used the re-ordering and movement of hospital supplies.

I'm also more likely to see “Kaizen Events” (sometimes called “Rapid Improvement Events” in healthcare) or, more recently, the “Daily Kaizen” model of improvement that Joe Swartz and I wrote about in our books.

Many might think that “quality circles” part of the past, when Total Quality Management was a bit of a fad in American hospitals (a fad that came and went). In contrast, the Japanese organizations I have visited (in healthcare or otherwise) are still using Quality Circles… and they are layering Kaizen and other Lean practices on top of that foundation, as I've blogged about before.

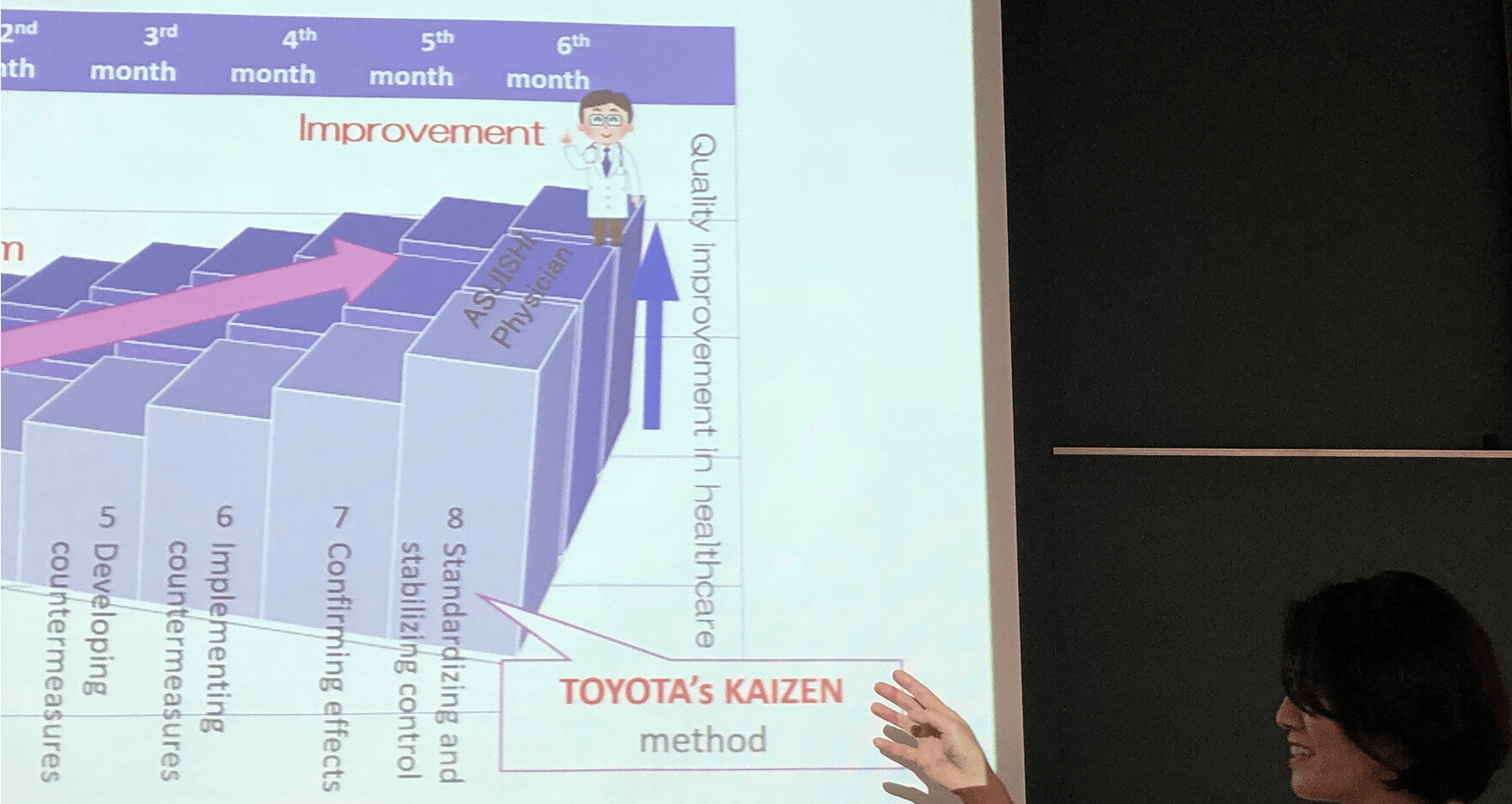

Now, back to the session I was able to attend at a Japanese academic medical center, where Toyota was teaching doctors about TQM and Kaizen. Here is a photo of the physician who was leading that effort for the hospital:

I'll share some of the handouts and my notes from the presentation.

Toyota shared a quote (from the leader of another company) about focusing on customers and creating value:

Principle #1 of the book Lean Thinking says that value is defined by the customer. We have to do more than “banish waste” or reduce waste. How can healthcare organizations and doctors work toward “quality creation” with patients and payers? How can we assure quality instead of trying to inspect it in?

The Toyota presenter also said the “relationship is very complicated” between TPS and TQM. He said that TPS focuses on eliminating “muda” (waste) through the dual pillars of JIT and Jidoka. He asked, “When you discover muda, how do you solve that problem? TQC provided the Kaizen method.”

Toyota says that Kaizen (continuous improvement) and “respect for people” are the two pillars of their “Toyota Way” management system. It's interesting that they would say or imply that Kaizen comes from TQM, not TPS. Either way, it has been a part of the Toyota approach for a very long time.

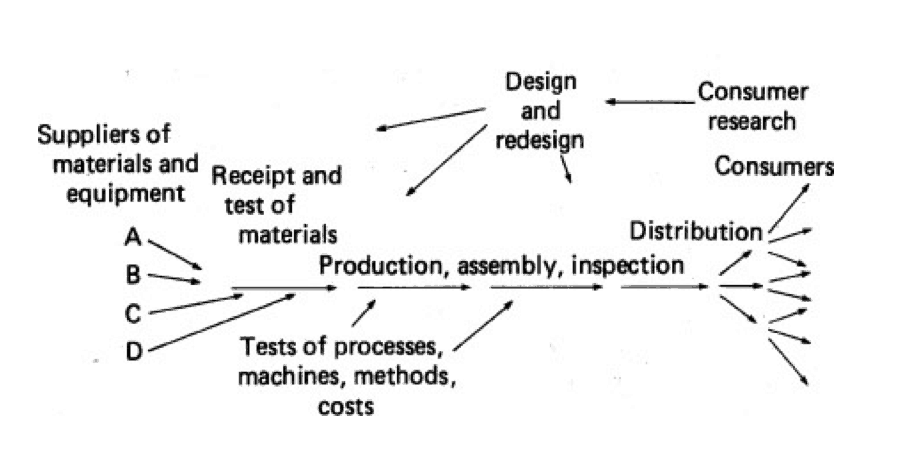

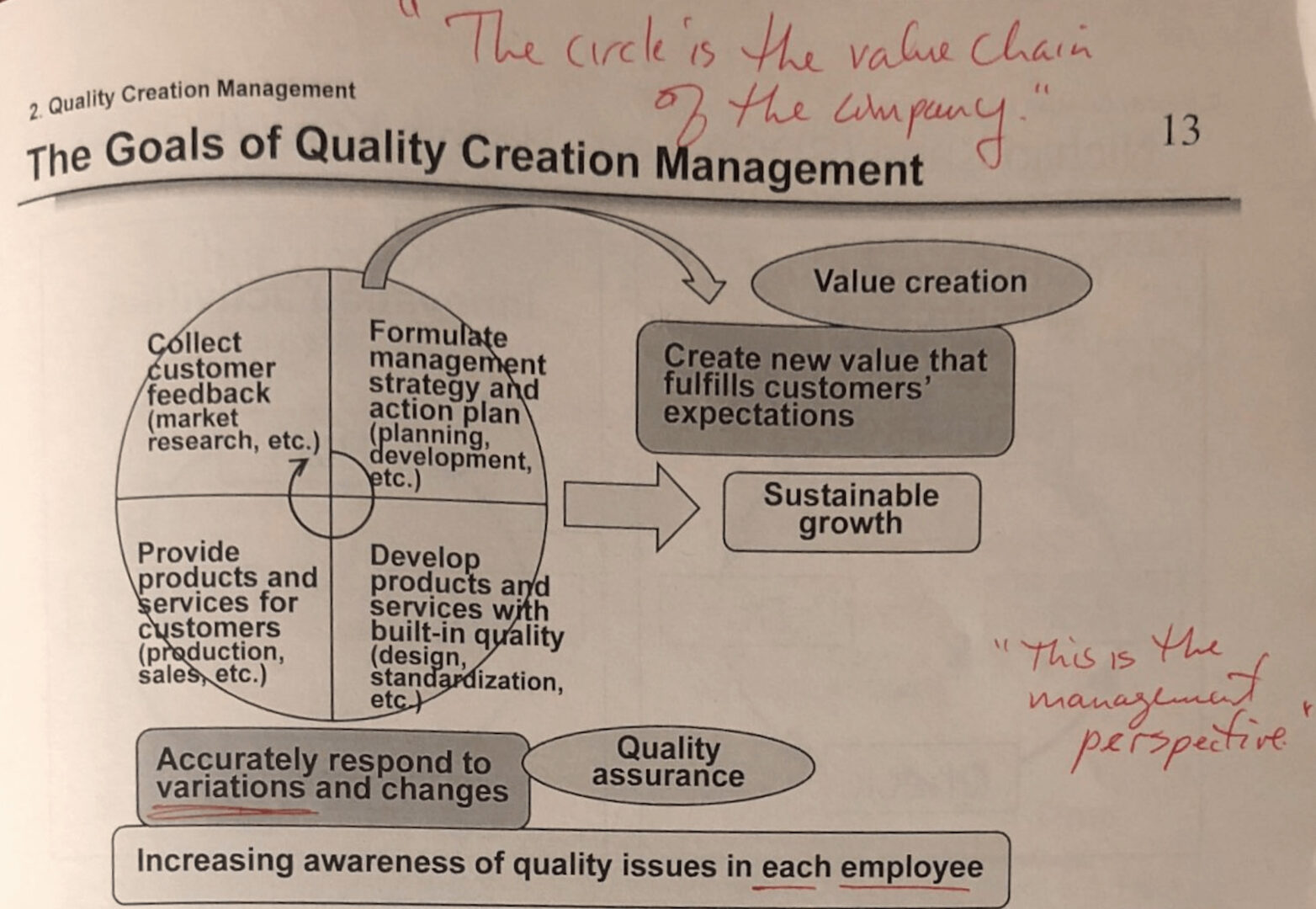

They also shared a diagram that reminds me of Dr. Deming's “production viewed as a system” figure from Out of the Crisis:

Here is their diagram, with my scribbled note: “The circle is the value chain of the company.”

What can we do in healthcare to “create new value that fulfills customers' expectations” and provides “sustainable growth” for the organization?

As the presenter talked about TQM, he said:

“This is not Toyota's quality management. This is what we learned… therefore doctors can learn.”

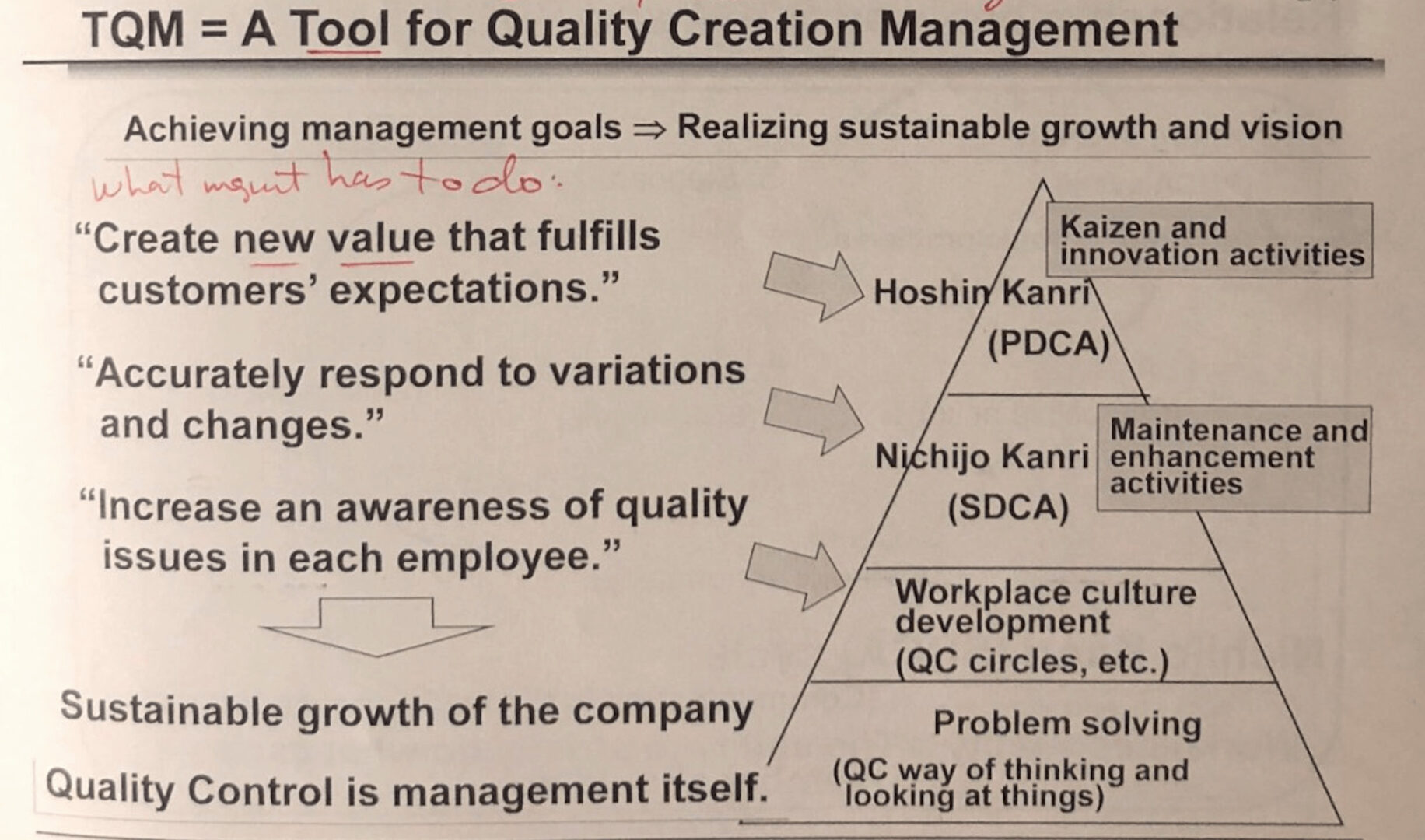

TQM is “a tool” for “quality creation management.” What management has to do, he said, is:

- Create new value that fulfills customers' expectations

- Accurately respond to variations and changes

- Increase an awareness of quality issues in each employee

“Quality control is management itself.”

My reflection on this: Leaders can't just create awareness of quality issues. Front-line staff can't fix every systemic problem that leads to poor quality. But, we can engage people and work with them… delegating and being a servant leader at appropriate times.

They showed a diagram with different types of improvement:

- Kaizen and Innovation activities

- Maintenance and enhancement activities

- Workplace culture development (QC circles, etc.)

- Problem solving (QC way of thinking and looking at things)

The lowest level, the base of the pyramid is problem solving, which is pretty reactive, by definition. Then, we move up toward creating more value.

He said:

“We want to solve the problem when it's small.”

Solving small problems helps prevent bigger problems. In healthcare, that's why it's so important to react to unsafe conditions and near misses. Instead of just reacting to harm incidents, we can do a lot to prevent that harm by reacting earlier when it's just the risk of harm.

Back to TQM:

TQM isn't framed just as a way to improve quality by reducing defects. It's about better understanding our customer and creating value. When I took a formal TQM class at MIT in 1997, understanding customer needs was a huge part of that methodology. Students in that same MIT program today study Lean and Six Sigma instead of TQM.

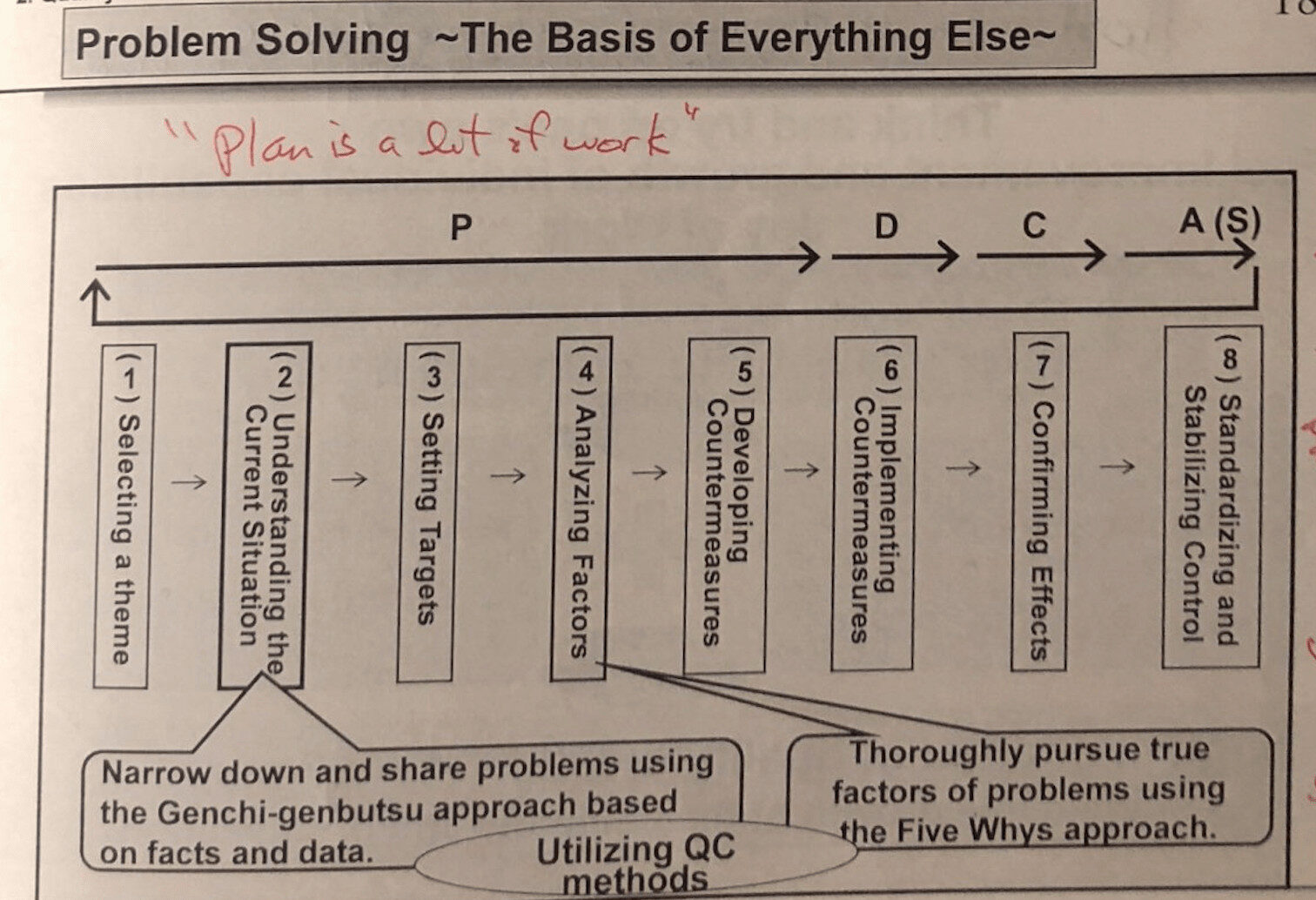

The presenter talked about the familiar PDCA: Plan Do Check Act.

He also talked about the SDCA cycle: Standardize Do Check Act. You'll read about SDCA in books from former Toyota people like the Richardsons, but you don't see that referenced in many other places.

“If there is no variation or deviation, we don't need SDCA.”

He showed a diagram with the 8-step Toyota problem solving model that maps to PDCA (see a webinar about this).

“Plan is a lot of work.”

Yes, we go through a lot of work before we start developing and testing countermeasures.

He added:

“It's very hard work standardizing what you've done. PDCA is improving the standard.”

He added that, when he first started teaching doctors:

“I didn't have enough confidence that the 8-step method would be useful to doctors. The doing is easier than thinking about it.”

He said when they started into action, he was “pleased” with the results of how it was going.

Toyota says problem solving is the basis for everything else, as it “becomes a part of your life, like a religion,” said the doctor.

He said:

“If you skip any step this will not work. People tend to skip Step 7. There are always side effects [to be found].”

At the same time, there's often a need for action instead of analysis.

“When a house is on fire, you don't think about how it happened. Put the fire out first. Once the fire is out, then you can stop problem solving.”

That's exactly the point of this one cartoon I helped create a few years back:

Our Toyota presenter then talked about management, strategy, and hoshin kanri (strategy deployment):

“I want the top management to have a vision and share it with the employees. Hoshin breaks down into each workplace and leads to Kaizen to meet them.”

He also added:

“Without a vision, there is no Kaizen because there is no problem (no gap).”

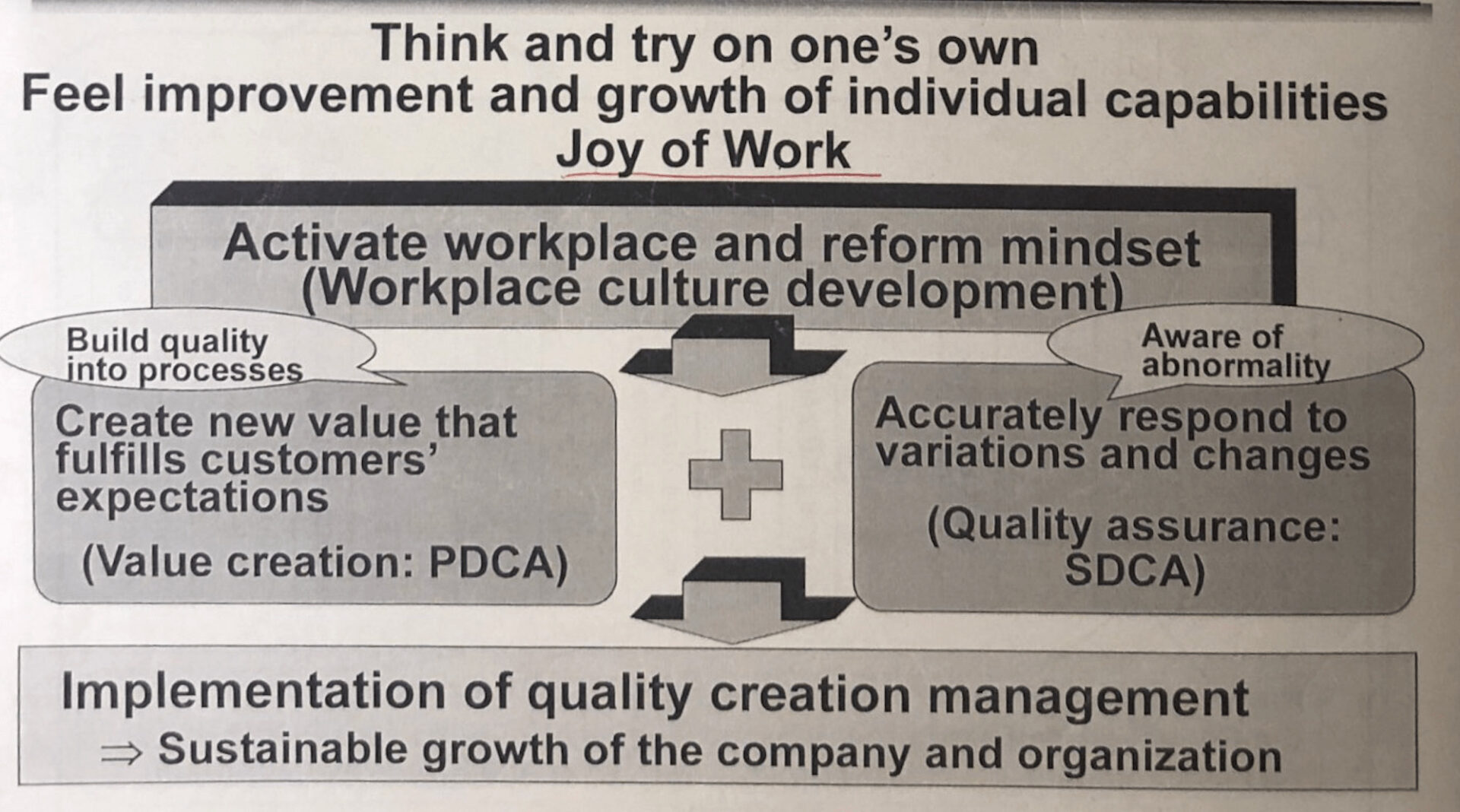

Here's a diagram that ties things together:

Our presenter said:

“Joy of work is Deming based.”

He added that they are now using the term “Process Quality Innovation” instead of “Total Quality Management.” Process Quality Innovation is the new name for their centralized TPS group, as I've blogged about:

He added:

“Everybody who works the assembly line studies the 7 Q.I. tools.”

In Part 1 of this series, I recalled a story where a Toyota employee in San Antonio said the same thing.

To wrap up this series of blog posts. This hospital we visited was “one of the few in Japan that does TQM” (and I've visited some of them).

“Probably no hospital has all participating — and that's because of the doctors,” said the doctor.

There's a range of Lean activity and TQM at Japanese hospitals ranging from “training doctors to do A3s” to “hospital-wide quality and Kaizen” activity. The same can be said for American hospitals, as well.

What do you think? What are your questions or reflections after reading this? What can you do to help your doctors learn, if Toyota learned from others too?

Please scroll down (or click) to post a comment. Connect with me on LinkedIn.

Let’s work together to build a culture of continuous improvement and psychological safety. If you're a leader looking to create lasting change—not just projects—I help organizations:

- Engage people at all levels in sustainable improvement

- Shift from fear of mistakes to learning from them

- Apply Lean thinking in practical, people-centered ways

Interested in coaching or a keynote talk? Let’s start a conversation.

![When Was the Last Time a Leader Around You Admitted They Were Wrong? [Poll]](https://www.leanblog.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/Lean-Blog-Post-Cover-Image-2025-07-01T212509.843-100x75.jpg)

Quality Creation reminds me of the perhaps more current lean term “Value Creation”, where value = Quality / Cost. I think it was Dr. John Toussaint espouse that equation. It’s encouraging to me whenever a hear a physician stand up for this work whether we call it TQM, TQC, or lean. Good slides too, thanks.

What is the MEDICAL ERROR RATE IN JAPAN ??

Great question.

I found a study online:

As shown in the data I’ve gathered here, rates seem to be about the same in most countries.

Per capita rates are almost exactly the same in Canada and the U.S., so we can’t blame capitalism or for-profit hospitals (not that all American hospitals are for-profit status)… nor does heavier government involvement seem to be the solution.

Letting the customer define value in healthcare sounds great in principle, but is much more complex in actual practice. If a patient goes to their primary care physician with lower back pain, odds are high that they will define “value” as getting an MRI and a prescription for a muscle relaxant or painkiller. Data shows that they would be very dissatisfied if their doctor responded to their complaint by telling them to take an Advil and go home to do some stretching exercises. But the proper clinical protocol for Lower Back Pain IS OTC meds and self-care (no imaging or Rx) for the first 4 weeks after initial presentation.The associated patient education required to properly treat that patient takes longer and is more costly than the “patient-defined” value” path. Far too many “Lean healthcare” projects executed without a basic understanding of clinical protocols

Each customer can, in way, define value… but that doesn’t mean the customer is always right in healthcare. Some patients want less pain in daily life, some want longer life at all costs, some want palliative care.

I think in therms of customer focus — reducing harm is a more important goal to me than superficial satisfaction.

The Society for Participative Medicine and the Engaged Patients movement have shown how clinicians and patients can work together to decide the best path of treatment. Obviously healthcare is not an industry where doctors take orders from patients, doing whatever patients want… but it seems we can also do better than the old paternalistic model of being told not to question doctors at all.

Most quality standards within the US and globally mandate some element of shared decision-making. And CMS reimbursement is influenced by patient satisfaction (of which “pain management” is one of the most significant predictors). And that’s kind of the gray area, right? Writing a pain med script for lower back pain ISN’T a reportable harm even. Ordering a CT scan for that same patient also isn’t a reportable event. Nor is writing an antibiotic script for a toddler in the ED with acute bronchiolitis. But they all absolutely can and do cause patient harm. They will all also improve a hospital’s HCAHPS scores and improve their reimbursement. So you have many many patient/hospital interactions every day that improve reimbursement (probably, with the appropriately worded documentation), patient satisfaction, shared decision-making, and have no impact on reportable events but still create negative outcomes and very real patient harm.

Harm events are also a little tricky. A hospital that doesn’t do daily imaging for in-treatment radiation therapy patients will probably have fewer documented harm events than a hospital that does (due to reduced ability to detection radiation delivered to organs at risk). A hospital with a higher percentage of high-acuity/low-compliance patients will also have a higher harm event rate than their counterparts, independent of actual clinical quality.

Too many “lean” projects are run with limited clinical knowledge (even with clinician involvement). Too many strategic healthcare decisions are made with only a superficial understanding of clinical quality and population health.