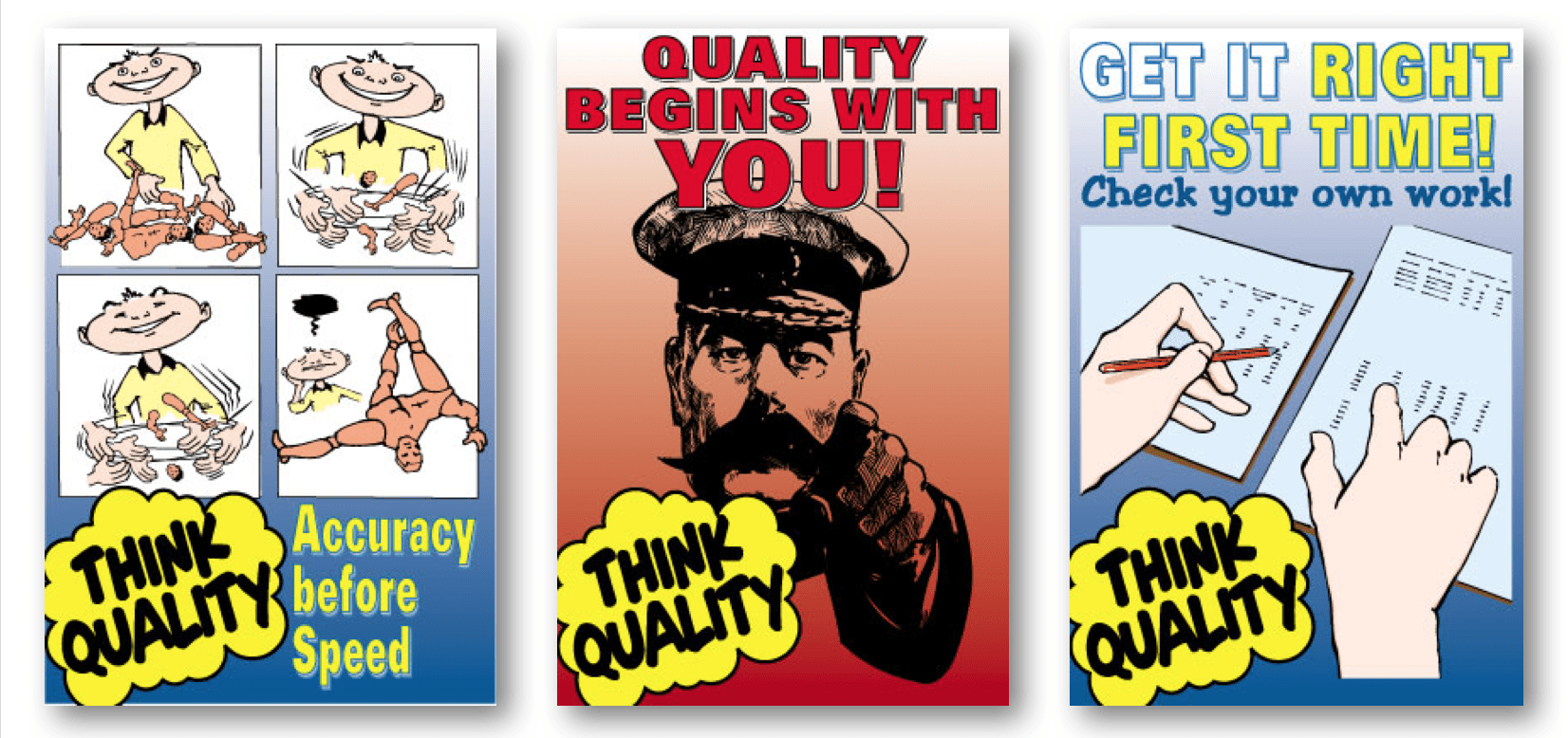

Back in 2007, I wrote a blog post that highlighted (if not mocked) so-called “quality posters” that are, I suppose, intended to be helpful:

Ten years later, posters like this are still sold online. I know organizations buy them because I still see similar types of posters in workplaces in various industries.

Next week, I'm facilitating the Deming Red Bead Experiment at Lean Startup Week. Normally, when I facilitate this, there's a projector and I, as part of the joke, show these “quality posters” on screen at one point in a bad attempt to improve quality and reduce the number of red beads.

The posters don't help. No surprise, eh?

Recently, a woman in the group had been (quite literally) born in the former Soviet Union.

“Why is Stalin on that poster?”, she asked.

Next week, I need to facilitate the session without a digital projector, so I purchased a two physical posters to use:

Again, I'm curious… who buys these? Apparently, there is a market.

When I placed the order, I almost felt the need to explain, “I'm buying these to use them for an ironic, jokey purpose.”

But, then again, I don't think they are selling them to be ironic. Who knows if the retailer thinks these posters are a good idea or not. They're selling them because there are buyers, I'm sure.

Maybe they are sitting around making fun of me for buying them. “We had these posters in stock for decades, not taking up much space, and some guy actually bought them???” (Hat tip to Jamie Flinchbaugh for that idea). Maybe they are working on a blog post titled, “How Are Quality Poster Buyers Still a Thing?”

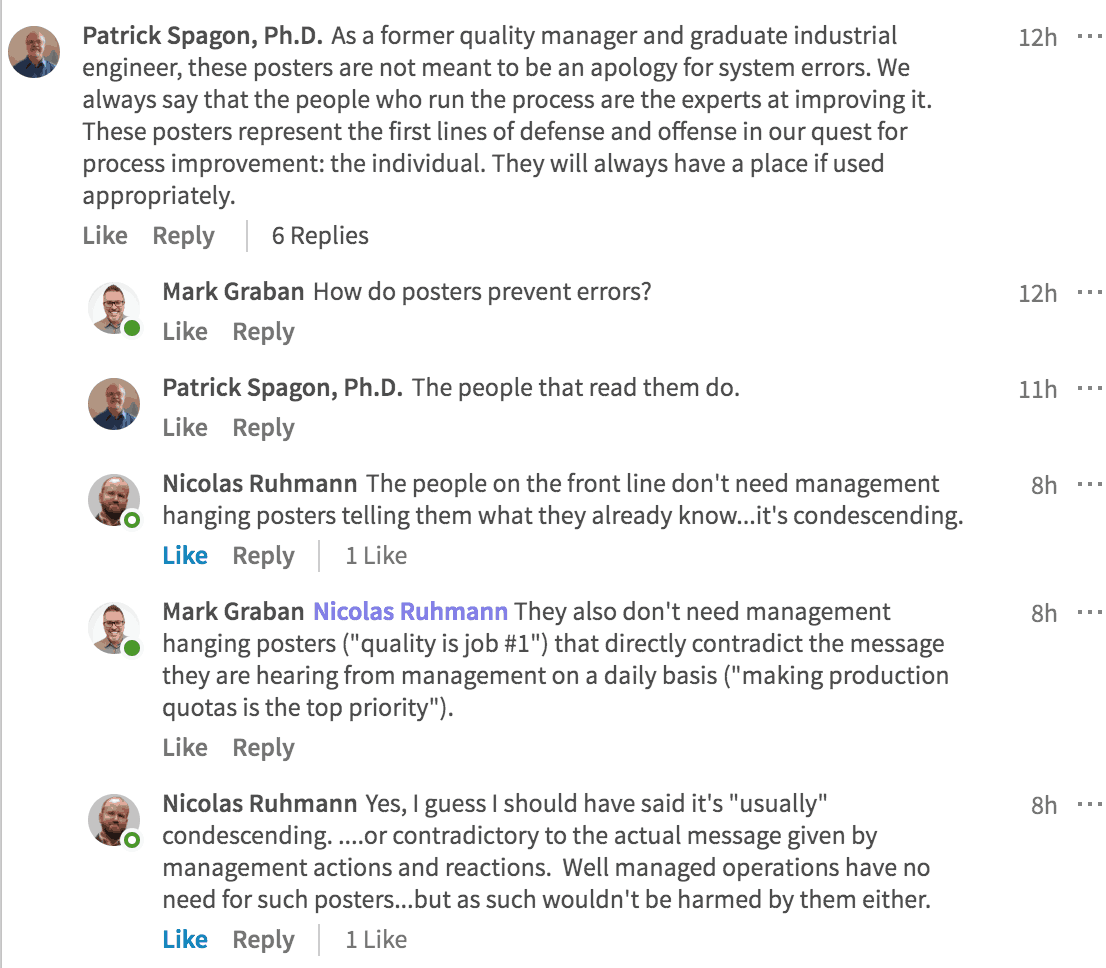

LinkedIn Discussion

As I often do these days, I posted this photo and a few comments on LinkedIn to gauge if there is interest in the topic and to learn what others would say.

Most people were “anti-poster,” such as Chris:

Mark Graban, I couldn't agree more. I've seen this rhetoric used as a corrective action mechanism numerous time, usually at the expense of morale. These posters imply undisciplined workers are the problem; problem's happen because the process allows them to.

I was a little surprised that some commenters said posters aren't harmful. One commenter said, basically, “they might not help, but what's the harm?”

My reply was:

There is “no harm” other than 1) wasting a little money on signs and 2) perhaps demotivating doctors and nurses who feel lectured by the signs instead of being engaged in improvement. People might see those signs and say, “Management doesn't understand the problems we face… they think we simply forget to wash our hands?”

One other example of the back-and-forth there:

Also, see this comment / question from a former Toyota leader and my reply (I've copied and pasted it into a comment below).

What Did Deming Say?

Dr. Deming's 10th point for management said bluntly:

10. Eliminate slogans, exhortations, and targets for the work force. Eliminate targets, slogans, exhortations, posters, for the work force that urge them to increase productivity.

He added right after, in Out of the Crisis, a story from a workplace about a poster:

[The poster reads] “Your work is your self-portrait. Would you sign it?”

No — not when you give me defective canvas to work with, paint not suited to the job, brushes worn out, so that I can not call it my work. Posters and slogans like these never helped anyone to do a better job.”

I wrote about this in healthcare a while ago, the laughable idea that nurses can sign a pledge saying they will not make errors that are designed into the system through faulty equipment:

Who buys the equipment? Management.

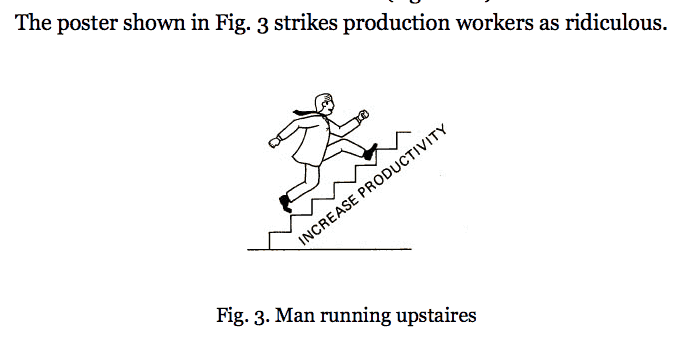

He shares an example of a comically bad poster:

It appears “upstaires” is a misspelling. I don't think it's an old-timey spelling. Maybe Dr. Deming or the publishing process were trying to show us nobody is perfect. Hey, books by myself and by Jeff Liker each had a printed typo on PAGE 1. It goes to show you can't inspect in quality.

https://www.leanblog.org/2011/11/proof-that-100-inspection-is-not-100-effectiv/

Deming wrote:

“What is wrong with posters and exhortations? They are directed at the wrong people. They arise from management's supposition that the production workers could, by putting their backs into the job, accomplish zero defects, improve quality, improve productivity, and all else that is desirable. The charts and posters take no account of the fact that most of the trouble comes from the system.”

…

The immediate effect of a campaign of posters, exhortations, and pledges may well be some fleeting improvement of quality and productivity, the effect of elimination of some obvious special causes. In time, improvement ceases or even reverses. The campaign is eventually recognized as a hoax. The management needs to learn that the main responsibility is theirs from now on to improve the system, and, of course, to remove any special causes detected by statistical methods.”

Ironically, a Google search on this topic found a “Deming Poster” that has a quote that's not exactly what Dr. Deming meant… I think he's being misquoted or the quote shows only a partial understanding of what's needed to improve quality. Yes, those words are directly attributed to him. But, Dr. Deming is misquoted or taken out of context a lot, as John Hunter wrote about here.

Deming said:

“Quality is made in the board room.”

Too often, it seems the quote gets used in a way where “everyone's responsibility” means the workers only. If only people would try harder and be more careful. Nope, that's not enough.

Yes, workers have a role to play in process improvement. The board and executives can't fix quality alone. Neither can the workers fix quality alone… nor is “process improvement” the only way to improve quality.

As Deming said:

“The intent of quality is dictated by top management. Quality can not be better than the intent.”

Deming, W. Edwards; Orsini, Joyce (edited by); Deming Cahill, Diana (edited by). The Essential Deming: Leadership Principles from the Father of Quality (p. 203). McGraw-Hill Education. Kindle Edition.

He also said:

“I should estimate that in my experience most troubles and most possibilities for improvement add up to the proportions something like this:

94% belongs to the system (responsibility of management)

6% special”

Deming wrote, in Out of the Crisis:

“Another roadblock is management's supposition that the production workers are responsible for all trouble: that there would be no problems in production if only the production workers would do their jobs in the way that they know to be right. Man's natural reaction to trouble of any kind in the production line is to blame the operators. Instead, in my experience, most problems in production have their origin in common causes, which only management can reduce or remove.”

Deming, W. Edwards. Out of the Crisis (MIT Press) (p. 402). The MIT Press. Kindle Edition.

John Hunter wrote about this on the Deming Institute blog:

“Complex systems have many leverage points and can be influenced in many ways. It is unreasonable to have a broken management system and blame those working within it for the naturally poor results than such a system creates. And executives have more authority and thus more responsibility for creating a good management system that is continually improving. But such a management system requires that everyone in the organization is contributing.”

It takes far more than posters. Remove the posters. Substitute leadership, as Deming said.

Please scroll down (or click) to post a comment. Connect with me on LinkedIn.

Let’s work together to build a culture of continuous improvement and psychological safety. If you're a leader looking to create lasting change—not just projects—I help organizations:

- Engage people at all levels in sustainable improvement

- Shift from fear of mistakes to learning from them

- Apply Lean thinking in practical, people-centered ways

Interested in coaching or a keynote talk? Let’s start a conversation.

There was an interesting comment / question from a former Toyota leader:

My reply:

I guess seeing signs or slogans in a Toyota plant (as I’ve seen in San Antonio too now that you mention it) would raise the same questions.

1) Do slogans and posters help?

Some have argued here that signs increase awareness… I’d suggest that vague, general awareness is far less helpful than the right processes and management behaviors. Does walking into a Toyota plant through the “safety arch” remind everybody that safety needs to be the top priority always? Maybe… but I think the key is walking the talk.

2) Do slogans and posters hurt?

In an environment where posters don’t line up with reality, I see them as being demoralizing. My guess (my hope) would be that signs would be LESS demoralizing at Toyota if managers lived up to the intent and the words on the posters.

That said, I’d guess that the relative impact of signs and posters is really minimal. Would it be ethical to do an experiment to remove the signs for a year and see what happened to the metrics? If I did that as a leader, I’d make sure to communicate to everyone that taking down the old posters doesn’t mean safety or quality are now less important. Maybe that’s one reason signs stay up – force of habit? It would “look bad” to take them down?

I think more specific signs, such as “Always wear your safety glasses” or “Don’t walk and text in the plant” are probably more helpful than vague platitudes about safety.

I’ve been waiting for this post. Its a good one! Thanks, Mark. Some thoughts– some posters are reminders. I’ve found some to be helpful, as in, “Oh yeah, I forgot about that.” Of course, this could be chalked up to a training problem (I’ve yet to work in a company that does a really good job of training–too much emphasis is placed on the individual to just ‘figure’ things out and there is definitely a stigma against those who aren’t able to do it). The comments from Dr. Spagon are typical for our western thought–i.e. the first line of defense is the individual. If we can’t get our heads around the concept that most of our issues are a systems problem and not issues created by individuals, poster slogans will continue to make sense. I’m not sure how we change this paradigm. Its tricky.

Thanks for the comment, Dan.

I think hospitals, for example, would be better served by better training and things like checklists to help prevent errors.

I don’t think anybody has ever hung a sign in an operating room that says, “Reminder: Don’t operate on the wrong side or the wrong patient!” I’m guessing nobody would think that sign would be helpful, but it’s probably more that surgeons don’t like to be reminded of their human fallibility or the systems that too often fail them and the patients?

But yes, the first line of defense is too often going after the individual. See today’s post for excerpts of Peter Scholtes talking about focusing on systems instead of people.

I’d add we can’t blame leaders for having been taught a certain way to manage (focus on people). It’s hard for people to unlearn what they’ve learned.