One challenge with teaching Lean is that there isn't aways a consistent definition that's used by everybody. Some of the definitions are really bad. Some of them are just different from others. Let's start with “different.” Is a lack of standardization in definitions of Lean a problem?

If you do a Google search for “what is lean?“, the first two results are about an illegal street drug concoction called “lean,” which isn't a good start (as I wrote about here). The third results and beyond are about the “Lean” that's the focus of this blog… an approach based originally on “Lean manufacturing.”

These definitions are pretty consistent, but not exactly the same:

Here is the Lean Enterprise Institute “what is lean?” page.

The affiliated Lean Enterprise Academy from the UK has a slightly different “what is lean?“

I have my own page with a bit of a Lean healthcare slant on “what is Lean?“

Here is a slideshare put together by Mike Rother and Jeff Liker:

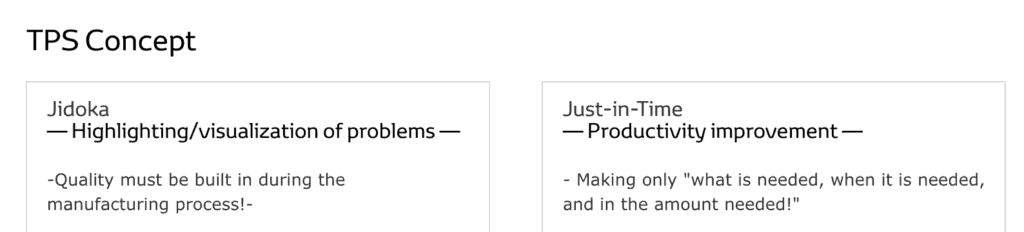

And then, there is the Toyota official page on the Toyota Production System, which includes:

“Toyota Motor Corporation's vehicle production system is a way of “making things” that is sometimes referred to as a “lean manufacturing system” or a “Just-in-Time (JIT) system,” and has come to be well known and studied worldwide.”

Toyota isn't saying Lean is exactly the same as TPS (Bob Emiliani says they are not the same).

Hear Mark read the post (subscribe to the podcast):

But, Toyota can't think “Lean” is too far off track, or they wouldn't send their Jamie Bonini to Lean conferences to talk about TPS, as I blogged about here:

Toyota, via Bonini, provides a helpful reminder that TPS is not just a set of tools. It's also a management approach, a philosophy, and an organizational culture that focuses on developing people.

But, not all efforts labeled as “Lean” share that approach, unfortunately. Are they more “L.A.M.E.” than “Lean?” Sorry if that question and term L.A.M.E. seems judgmental. In recent years, I've started to question if this framework and term just makes people double down on what they already believe to be true.

Some Shaky Definitions

I often read articles or websites that have some nutshell definition of “Lean” that seems very incomplete or just incorrect.

For example, I don't think the American Society for Quality (ASQ) definition of Lean is very good because it focuses on “techniques and activities” for operations and supply chain, without any mention of a management system or an approach to engaging people.

Sometimes, it's an article author who perhaps didn't hear things right from the subject of the article. Or, what they wrote was accurate (meaning they captured what the person told them), even if the underlying definition of Lean is not.

I've tweeted a few of these shaky definitions recently:

I don't think it's accurate to say Lean “starts with constant measurement.” Yes, measurement is important. Lean organizations tend to have “true north” categories of Safety, Quality, Delivery, Cost, and Morale.

But, “constant measurement” can lead to a lot of overreacting, unless our approach to “Lean Daily Management” takes basic statistical methods into account.

“Project management?” I have no idea where that faulty definition comes from. TPS (therefore Lean) “was about improving flow and quality of production,” would probably be a more accurate statement.

Lean Six Shaky

I have nothing against Six Sigma. But, I do complain quite often about “Lean Six Sigma” definitions of Lean being very lacking (and I have a separate blog about that).

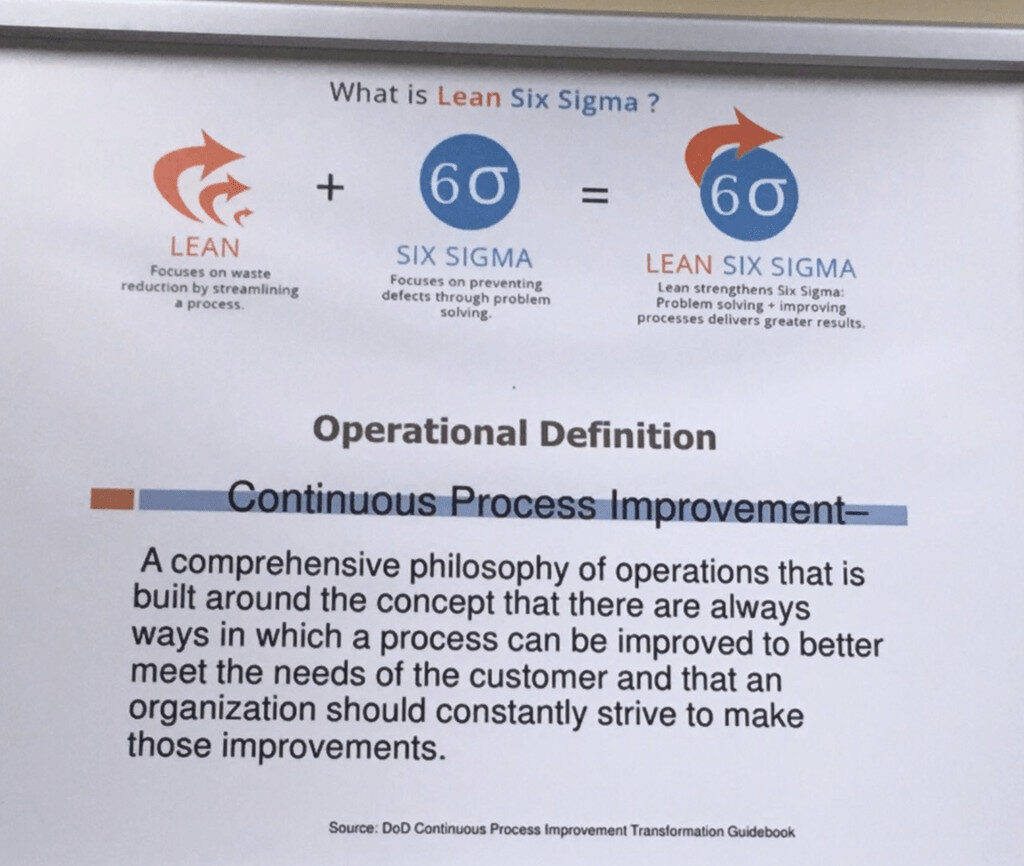

A photo of a “Lean Six Sigma” framework that's apparently hanging in a U.S. Department of Defense office is wrong about Lean (h/t to Chris on Twitter who understandably said “never seen it put this way”).

Unfortunately, I've seen this a lot (hence my other blog).

The text says Lean:

“Focuses on waste reduction by streamlining a process.”

It's tough, perhaps, to give a short definition of Lean. Nothing in that sentence is really that wrong, it's just woefully incomplete. Lean focuses on providing value to the customer, not just waste reduction. Lean isn't just about process, it's about people. It's not just about streamlining and improving flow, it's also about quality (see, again, the Toyota definition of TPS). An except from Toyota is below:

The DoD (and it's not just the DoD who gets this wrong) dichotomy of Lean + Six Sigma really falls apart when they say Six Sigma:

“Focuses on preventing defects through problem solving.”

The incorrect implication is that ONLY Six Sigma does this. That's false.

Back to my earliest days of anything Lean (back at GM in the mid 1990s), we were definitely focused on preventing defects through problem solving. Lean provides many methods and mindsets for that.

Defect reduction is hardly the exclusive domain of Six Sigma.

Lean Sigma defenders will say, “We didn't say Lean doesn't do that,” but the implication in the faulty Lean Sigma dichotomy is that you NEED both to deliver greater results. You can choose to use Lean and Six Sigma together in the same organization. But I, like many, reject the notion that you can combine Lean and Six Sigma into a single coherent methodology.

A cat and poodle together in a cage doesn't make them a “catoodle:”

Here is the discussion we had about this incorrect Lean Sigma framework on LinkedIn.

A Better Short Definition

To end on a positive, I like this short definition better:

Lean is not just about cost reduction… it's more about “respect for people” and changing the way we do things… which leads to lower cost as an end result.

Please scroll down (or click) to post a comment. Connect with me on LinkedIn.

Let’s work together to build a culture of continuous improvement and psychological safety. If you're a leader looking to create lasting change—not just projects—I help organizations:

- Engage people at all levels in sustainable improvement

- Shift from fear of mistakes to learning from them

- Apply Lean thinking in practical, people-centered ways

Interested in coaching or a keynote talk? Let’s start a conversation.

The lack of a definition of Lean early-on (ca. 1988-1990) was unfortunate because it led to many incorrect and confusing definitions, and thus a wide range of understanding and practice. Since no definition of Lean existed, I created one 15 or so years ago to teach my graduate students. It is: “A non-zero-sum principle-based management system focused on creating value for end-use customers and eliminating waste, unevenness, and unreasonableness using the scientific method.” Reducing the definition of Lean to “respect” may be OK for Lean — to help it recover from its checkered past of zero-sum practice — but it is not OK for defining TPS because, as Toyota says, TPS is “A production system which is steeped in the philosophy of ‘the complete elimination of all waste’ imbuing all aspects of production in pursuit of the most efficient methods.” Finally, the different definitions of Lean and TPS further highlights the differences in thinking and practice.

I’d guess that LEI had a definition of Lean on their website from the beginning, about 20 years ago. It seems inaccurate to say “no definition of Lean existed.” More accurate to say you didn’t like their definition or others.

I looked far and wide before coming up with my own definition ca. 2001 when I began teaching Lean leadership. Twenty years ago, if LEI had a definition on their web site, I’m sure I would have used it. The Wayback Machine of archived web pages does not show a definition of Lean on LEIs web site 1998-2003.

Page 12-ish of The Machine That Changed the World sort of has a definition, but it’s not a pithy sentence or two.

This can probably be browsed via Google Books for those who don’t have a copy handy.

Lean is harder to define than a duck?

Would it evolve this way?

1) A duck is not a pigeon. Ducks are better in every dimension and we have data!

2) A duck follows these principles, that’s what makes it a duck.

3) The key question is how to be more like a duck. Every type of animal can be more like a duck and here’s more about what makes a duck a duck.

4) It’s not about using a duck’s tools (like adding a bill to one’s face), we have to understand how a duck thinks.

5) Now we REALLY understand how a duck thinks…

6) A duck is a strategy ;-)

That was the problem at the time; definitions of Lean were not concise. They were paragraph, chapter, or even (almost) book-length.

I wonder if the Toyota definition of TPS doesn’t include “respect for people” because that’s assumed to be part of the culture. The “Toyota Way” framework points out the “equally important pillars” of “continuous improvement” and “respect for people.”

Hi Mark,

Perhaps it would help to treat the variation in the definition of lean in the same manner we treat variation in any process: try to understand whether they belong to a common system or fall outside the system. If they share a common system, generally define lean in similar ways with “random” variation, I think we’re in good shape. We can focus on the harder task of reducing systemic variation by developing an operational definition of it.

If the definitions do not form a common system, then we should try to understand each definition and what it’s trying to achieve. If we can’t change the particular definition, we can at least develop countermeasures to those special definitions.

Ultimately, the only definition that matters in our context is an operational definition, one that people can realize by performing certain operations. Any other definition serves to communicate an idea. And if the idea is communicated, the objective is met–awareness is raised.

Regards,

Shrikant Kalegaonkar

Great post Mark! You sparked some thoughts for me… Awhile back I had stickies on my wall with a similar collection of definitions. My colleague Darrell Damron and I now use these definitions we like and don’t like to clarify with our government clients what we mean by Lean. Many leaders are grateful to think of Lean with a broader definition. They see themselves, their organization’s challenges, and their leadership hopes in it.

While it’s important to honor and understand origins, we also continue to learn and gain deeper insights. Through dialogue with others on this journey and our own reflection, at DES LTS we now embrace this definition,

“Lean is a human centered philosophy of work that creates a culture of curiosity, collaboration, and care so that we deliver better value to Washingtonians and make public service a gratifying experience for generations to come.”

The cascading logic is what’s important. For example, we start with seeing the humans in our system as central, both customers we serve and team members we work with. Then that calls us to listen carefully and regularly to understand them and pursue meeting their expectations. Then we have to develop tools and methods to go about listening, measuring, improving, and keeping tabs on how we are doing.

That human centered philosophy and its principles lead to strategy and org design decisions too. Decisions about the problems we solve, the capabilities we build or hire, the processes we design or improve, the acts we celebrate, the messages we communicate, the management systems that guide us, etc.

We start with a human centered philosophy of work. The rest flows from there. That’s how we see Lean today!