Along my Lean journey, I learned an expression about the role of leaders and I shared this in my first book Lean Hospitals.

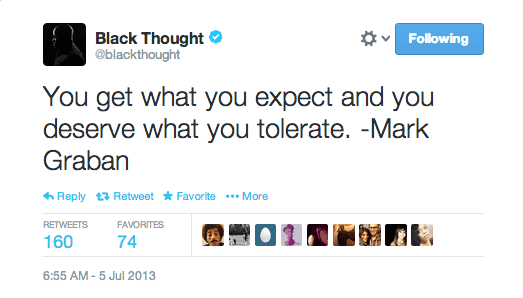

Last year, this phrase somehow “went viral” via Twitter when Tariq Trotter, aka @BlackThought, (co-founder of hip-hop “neo-soul” band The Roots) tweeted the phrase with attribution to me (which isn't quite correct because I didn't create the quote, I learned it from somebody):

And here is an image of it, in case it ever disappears for some reason:

I would still love to know how that phrase got into his brain and his twitter feed. Does he have a relative who is working in a hospital and got exposed to my book? I learned the phrase during my time at J&J from one of our Lean coaches and I don't know the exact origin.

Here is how I shared it in my book, in a section on “standardized work”:

“There is a phrase that we use that attempts to capture the responsibility of leaders in overseeing standardized work: “You get what you expect and you deserve what you tolerate.” As leaders, if you expect that employees will follow the standardized work, you have to take time to go and see, to verify that the standardized work is actually being followed. If you tolerate people not following the standardized work, you deserve the outcomes that result from the standardized work not being followed.”

Lean Hospitals, 3rd Edition (Graban)

“You get what you expect” — leaders often sit back and whine that their employees aren't following bundles, protocols, or procedures. Leaders need to expect that they will be followed. This means that leaders have to work together with employees to figure out HOW to make that happen. If supplies aren't available, help fix that. If there's not enough time to do things the right way, help fix that.

Toyota certainly expects that no car or truck comes off the assembly line with a door missing. So, they make sure their systems make that happen. None of this is about “beating up on employees” in the sense of “I expect it, so you'd better do it!” It's about working together and making it possible for the right things to happen.

Imagine a hospital where leaders expect that infections, bed sores, and patient falls are going to happen. What's the reaction when one of these things occurs? The leaders might shrug their shoulders and maybe say “well, we're better than the average hospital.”

Now imagine a hospital where leaders expect that preventable harm does NOT happen. If an infection occurs, the leaders work with staff to investigate why that happened (looking at the process, not blaming the people). They work to implement countermeasures that will prevent future infections – because we believe it's possible to eliminate them.

“You deserve what you tolerate.” — the thought here is that leaders need to proactively manage their processes to get the results they are expecting (and desiring). Far too often, I see news reports where something bad happens in a hospital (like the Quaid twins getting the wrong medication), and a C-level executive says, “Procedures were not followed, and there's no excuse for that.”

I'm sure the day that error occurred was NOT the first day when procedures were not being followed. The COO can blame workers… but it's really the COO who is to blame. If the COO and other leaders were unaware that procedures are routinely not followed in hospitals… or if the COO knew and TOLERATED this condition, than the COO and the hospital deserved the embarrassment and shame. The Quaid twins, of course, deserved none of this.

If you're a hospital leader who walks by water on the floor in a hallway (and ignores it), then you deserve to have somebody slip and fall. If you walk past checksheets on the wall that indicate hourly rounding is not happening (and ignore it), then you deserve to have patients fall or get bedsores.

Again, the patients deserve none of this.

If you tolerate bad processes, you deserve bad results. That's true in any organization, I think.

What do you think of the quote and my thoughts?

Please scroll down (or click) to post a comment. Connect with me on LinkedIn.

Let’s work together to build a culture of continuous improvement and psychological safety. If you're a leader looking to create lasting change—not just projects—I help organizations:

- Engage people at all levels in sustainable improvement

- Shift from fear of mistakes to learning from them

- Apply Lean thinking in practical, people-centered ways

Interested in coaching or a keynote talk? Let’s start a conversation.

![What’s Your Organization’s Real Mistake Policy? [Poll]](https://www.leanblog.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/Lean-Blog-Post-Cover-Image-2025-07-17T085114.134-100x75.jpg)

Via Karen Martin:

I can’t believe this post has only gotten one comment. It has been driving my approach to policies, procedures, and problem solving as an assistant nurse manager for the past month. I’ve been quoting it, printing it and handing it out to all the staff. I had read it in your book, but seeing it broken down again on the blog reinvigorated it. Thanks Mark!

Thanks, Andy. Can you think of an example of something a hospital “tolerates” that it should not?

Hospitals (and providers) tolerate 12 hour shifts for nurses and 80 hour weeks for residents. You can’t expect to improve safety if you tolerate and maintain a system that mentally and physically exhausts providers.

Sad, but true. Excellent example, Andy. The healthcare often expects the humans working in these organizations to be superhuman – never get fatigued, never forget things, never mess up. It’s not possible.

Hence, the need to improve the system (reasonable working hours, etc.) and improve processes (to incorporate error proofing, etc.).

[…] You Get What You Expect and You Deserve What You Tolerate by Mark Graban. “If you tolerate bad processes, you deserve bad results. That’s true in any organization.” […]

[…] I came across a slightly different expression from Mark Graban that captured the essence of what I wanted to […]

Its been a guiding principle for my management style since 2000 when I learned from someone…not sure who I heard it from, but it is old.

Mark,

FYI – I introduced that phrase into J&J during my 5 day Lean Seminars and Consulting at Ohio Health and Florida Hospitals. It came from a Reader’s Digest article back in the 1970s. Not sure of that source though. It is in most of my books.

Charlie Protzman