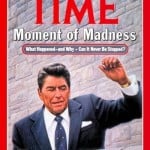

The year is 1981. A Major League Baseball strike interrupts the season. We're in the midst of the Cold War. President Reagan is shot. Kim Carnes' (not to be confused with ThedaCare's Kim Barnas) tops the charts for the year with “Bette Davis Eyes.” And, Toyota has zero manufacturing presence in the United States… yet.

What became known as “Lean” in 1988 (25 years ago, I'll be blogging about this soon), was exotic enough to be referred to commonly as “Japanese manufacturing practices,” as evidenced by a brilliant and prescient HBR article by Prof. Robert B. Hayes: “Why Japanese factories work.” But, the things that set some Japanese factories apart were really just good, solid, fundamental management practices.

I found the article in a stack of papers and course materials from my time as a grad student at MIT when straightening up some things over the weekend at home. There were some things I threw away, but this article is a keeper.

The article (freely available on the HBR website, thankfully) is summarized in a subtitle:

“They succeed not by using futuristic techniques, but by paying attention to manufacturing basics.”

I'd like to think the same idea would apply if Hayes wrote a follow up article today called “Why Lean hospitals work.” The best Lean hospitals focus on the basics of running a hospital – designing and executing processes in a disciplined manner.

It was easy for American manufacturing leaders in 1981 to make excuses for why Japanese factories were performing well, including government subsidies, currency manipulation, or the idea that they must be relying on advanced robotics or what some might call “the factory of tomorrow.” But, as Hayes said:

“The modern Japanese factory is not, as many Americans believe, a prototype of the factory of the future. If it were, it might be, curiously, far less of a threat. We in the United States, with our technical ability and resources, ought then to be able to duplicate it. Instead, it is something much more difficult for us to copy; it is the factory of today running as it should.”

Leading Lean hospitals like ThedaCare and Virginia Mason are the hospital of today… running as they should (or reasonably close it to without yet reaching any state of perfection that Toyota has not even reached in 2013).

What did Hayes see in Japanese factories?

- They were “exceptionally quite and orderly” as the result of “attitudes, practices, and systems that plant managers had carefully put into place over a long period.”

- The “almost total absence of inventory on the plant floor,” as “stoppages caused by breakdowns at earlier process stages almost never occurred.”

- Machines were “not overloaded” and fan slower than they would have in the U.S., lasting much longer due to that and better maintenance.

- Error proofing (classing Toyota “jidoka,” although he didn't use that term) meant workers could manage multiple machines without having to watch them constantly.

He also pointed out the “no-crisis atmosphere,” pointing out that “American managers actually enjoy crises; they often get their greatest personal satisfaction, the most recognition, and their biggest rewards from solving crises… To Japanese managers, however, a crisis is evidence of failure.”

His statement about American managers could apply to many healthcare managers today in 2013.

One thing that strikes me about the Hayes article is how much is focuses on culture and management systems. There are some who criticize the “early days” of the Lean movement as being too focused on tools. But, I've re-read a lot of the early material and his is not the case.

Hayes states very directly that:

“the basis of this system is not simply an appropriate arrangement of people and machines. It is a way of thinking.”

Some management mindsets that Hayes wrote about included:

- Never being satisfied, as “they regard all problems as important,” “a defect is a treasure,” and “they will not be satisfied with less than perfection” (as a long-term goal).

- “Thinking in quality,” not just building it in. “Management attitudes and actions constantly reinforce this feeling [of making high-quality products].”

- Working with suppliers to improve and to solve problems.

- Taking the long-term view.

- Continually developing people's skills.

- Having a commitment to employees (so that they, in turn, can have a commitment back to the company).

- Viewing the workers as “the experts” as a source of input for problem solving.

Great quote from the article:

“I get the impression,” remarked one Japanese visitor to the United States, “that American managers spend more time worrying about the well-being and loyalty of their stockholders, whom they don't know, than they do about their workers, whom they do know. This is very puzzling. The Japanese manager is always asking himself how he can share the company's success with his workers.”

He is very prescient about the challenge of getting other organizations (yet alone other industries) to embrace this style of management that we'd now call “Lean”:

The Japanese have never considered the production problem solved, never underestimated the challenge of building and improving the “factory of the present.” There are no magic formulas—just steady progress in small steps and focusing attention on manufacturing fundamentals. This is why their example will be so hard for American companies—and American managers—to emulate.

He also commented how, in 1981, that American had less elitist managers compared to Europe… but he sensed this was changing, as Hayes commented:

With some shock, we recognize the emergence of elitism and lack of trust in the United States—managers who isolate themselves from workers, both physically and emotionally; who have no direct experience in the businesses they manage; who see their role as managing resource allocation and other organizational processes rather than as leadership by example.

The exponentially widening spread between worker pay and CEO pay over the past 30 years is evidence of this (going from 26:1 to 1979 to 200:1 in 2012).

I'd invite those of you in healthcare to read the final paragraph of Hayes' piece by replacing a few words… as I think the advice applies just as well to healthcare in 2013 as it did (and still does) to manufacturing in 1981.

Improving our manufacturing competitiveness does not lie with the “last-quarter touchdowns,” the “technological fixes,” or the “strategic coups” that we love so much. Instead, we must compete with the Japanese as they do with us: by always putting our best resources and talent to work doing the basic things a little better, every day, over a long period of time. It is that simple—and that difficult.

Amazing stuff. Read the whole HBR article here.

Please scroll down (or click) to post a comment. Connect with me on LinkedIn.

Let’s work together to build a culture of continuous improvement and psychological safety. If you're a leader looking to create lasting change—not just projects—I help organizations:

- Engage people at all levels in sustainable improvement

- Shift from fear of mistakes to learning from them

- Apply Lean thinking in practical, people-centered ways

Interested in coaching or a keynote talk? Let’s start a conversation.

“There are some who criticize the ‘early days’ of the Lean movement as being too focused on tools.”

Exactly right. It seems to me it was when the first fad wave hit and you had lots of people that didn’t study and learn churn out their super oversimplified “lean” that the cookbook tool approach took off. The initial people studied Toyota and other companies in Japan (mainly) and those people understood it was a DIFFERENT way to manage – not using a couple tools.

But it was hard to figure out how to actually do it in the USA while it was easy to offer training in setting up QC circles and the rest of it, so much of that happened.

Here are some early reports (so early it preceded the lean term’s widespread use). It also means the focus hasn’t already been set by the Machine that Changed the World but it is the same stuff that those that studied in 1980, 1990, 2000 or 2013 saw – it is more about respect for people and using everyone’s brain than any specific tool.

Peter Scholtes report on first trip to Japan, 1986

Managing Our Way to Economic Success: Two Untapped Resources – potential information and employee creativity by William G. Hunter, 1986

15. How to Apply Japanese Company-Wide Quality Control in Other Countries by Kaoru Ishikawa. (November 1986)

Eliminating Complexity from Work: Improving Productivity

by Enhancing Quality by F. Timothy Fuller, 1986

On Quality Practice in Japan by George Box, Raghu Kackar, Vijay Nair, Madhav Phadke, Anne Shoemaker, and C.F. Jeff Wu. (December 1987)

The early lean stuff was much like what is discussed there (though these were before the “lean” term had taken hold). These were all first published as reports at the University of Wisconsin – Madison Center for Quality and Productivity Improvement founded by my father and George Box.

Thanks for sharing those articles, John!

Good stuff,

The example of US managers spending agonizing hours justifying a capital purchase and then spending a half hour a year on developing employees is still the case.

On the other hand, I am looking for an analogy in healthcare for inventory being the ultimate evil. Yes, supplies are a major expense and there are inventory opportunities all around, but a typical supply room on a nursing unit may have $10,000 worth of supplies. What benefit do I get from reducing that to $5,000 or $2,000 even other than a one-time inventory savings?

Yes, that was a great point Hayes made about the time spent agonizing over equipment, yet giving scant attention to developing people.

I don’t think “inventory is the root of all evil” in healthcare as it is in manufacturing. I think the amount of inventory is a good proxy for the level of good management – spending time on developing quality and uptime (through preventive maintenance) leads to lower inventory (the need for less inventory).

I think the worst form of waste in healthcare is defects – poor quality and patient harm. That’s not only morally the right thing to work on, but it also has a bigger financial impact to the organization than reducing inventory.

I’d make patient safety my primary focus in a Lean healthcare effort, not inventory (although there can be multi-million dollar opportunities that result from fixing the healthcare supply chain).

Awesome Comparison!! Thanks for posting such innovative

article..

Amazing article Mark, thanks for bringing it up!

Haven’t read the complete HBR text, but the quotes you have included here go straight to a key point which has been ignored too often: Huge competitive value lays in doing the basics a little bit better everytime, never being satisfied with its current performance.

This is mainly a cultural thing where Japan has centuries of advantage over Western societies. As bushido preaches “Perfection is an unclimbable mountain that must be climbed every day”.