Scroll down for how to subscribe, transcript, and more

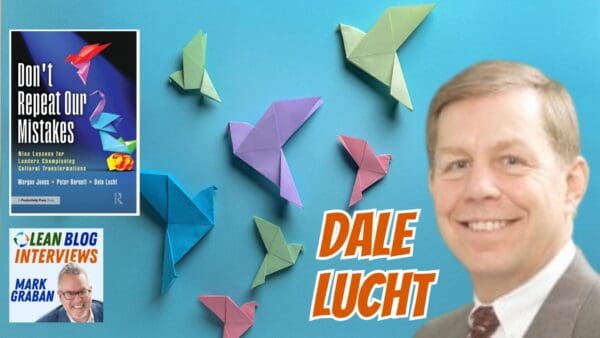

My guest for Episode #534 of the Lean Blog Interviews Podcast is Dale Lucht, co-author of the new book Don't Repeat Our Mistakes: Nine Lessons for Leaders Championing Cultural Transformations.

Dale has led Lean transformations in manufacturing, healthcare, and financial services, and he brings decades of leadership experience shaped by mentors such as George Koenigsaecker and the Shingijutsu consultants.

In our conversation, Dale reflects on what it takes for a senior leader to go beyond being a “sponsor” of Lean to becoming a true champion. He shares stories of learning by doing, coaching from mentors, and mistakes that became turning points. We talk about leadership habits such as visibility, simplicity, curiosity, and the shift from solving problems yourself to developing others as problem solvers. Dale also discusses how to sustain progress and avoid the common plateau many organizations hit after a few years of Lean practice.

Dale and his co-authors, Peter Barnett and Morgan Jones, wrote Don't Repeat Our Mistakes not just to highlight what works, but also to candidly share lessons learned when things didn't go as planned. With proceeds from the book supporting the Michael J. Fox Foundation, it's both a professional guide and a personal legacy project. Whether you're a senior executive, a Lean coach, or someone working to influence leadership in your organization, this episode o

Questions, Notes, and Highlights:

Early Career & Lean Origins

- What's your Lean origin story, and how did you get started?

- What was it like learning from George Koenigsaecker and Shingijutsu?

- Can you share an example of the “homework” they gave you as a plant GM?

- How did those early lessons shape your leadership approach?

Leadership Lessons & Mistakes

- What mistakes or challenges did you experience that led to learning?

- Why do so many organizations plateau after a few years of Lean?

- What distinguishes improvement from true transformation?

- How can leaders practice self-coaching before coaching others?

- What shifts do leaders need to make–from solving problems themselves to coaching others?

- Why is curiosity such an essential leadership habit?

Cross-Industry Experience

- How did your transition from manufacturing into healthcare come about?

- Did you see the same progression from tools to leadership change in healthcare?

- How did you approach leading change in financial services?

The Book: Don't Repeat Our Mistakes

- What did you and your co-authors hope to capture in Don't Repeat Our Mistakes?

- How did the title and focus on mistakes come about?

- Were the leaders you interviewed open to sharing their own mistakes?

Practical Advice for Leaders

- How can someone move from being a Lean sponsor to being a true champion?

- How should leaders pick which habits or lessons to focus on first?

- What advice do you have for influencing senior leaders when coaching “up” isn't invited?

- How do organizations prevent backsliding when leadership changes?

This podcast is part of the #LeanCommunicators network.

Full Video of the Episode:

Thanks for listening or watching!

This podcast is part of the Lean Communicators network — check it out!

Key Quotes:

“Most organizations start with process improvement–but lasting change requires a transformation in leadership.”

“Leaders have to reach that tipping point where culture change isn't a chore, but a source of value and reward.”

“Curious leaders create curious organizations. Rewarding experimentation is how you sustain improvement.”

Automated Transcript (Not Guaranteed to be Defect Free)

Introduction

Mark Graban:

What does it really take for a senior leader to not just support Lean in name, but to truly be a champion for it? My guest today, Dale Lucht, has explored that question with executives around the world as co-author of the new book Don't Repeat Our Mistakes: Nine Lessons for Leaders Championing Cultural Transformation. So today, we're going to talk about the lessons these leaders have learned through trial, error, and persistence, and how to turn self-coaching into team coaching, how to build the habits that sustain cultural change. So, Dale, welcome to the podcast.

Mark Graban:

How are you?

Dale Lucht:

I am doing great today, Mark.

Mark Graban:

It's great to see you again. After, boy, going back maybe 15 years–Healthcare Value Network and Catalysis circles–crossing paths in healthcare-land.

Dale Lucht:

Yes, I spent from 2010 to 2018 in healthcare.

Dale's Lean Origin Story

Mark Graban:

So I've got, I think, right, 15… 15 years, and you've got a varied career. And, you know, as we normally start off here, I'd love to hear your Lean origin story, and then maybe, you know, we'll kind of talk about what you've learned and seen, similarities and differences across industries. But where did things get started for you, Dale?

Dale Lucht:

Well, if you think back, oh, 35 years ago, we were starting to read in the press about the Toyota Production System, especially in manufacturing. And I was in manufacturing at the time and became enamored with some of the systems that Toyota was using. So we were doing bits and pieces of it at the company that I was with, and I decided I wanted to join a firm that really got it and was moving forward. So I found that firm not too far away in The HON Company, HNI Corporation, and had the good fortune in joining them to have George Koenigsecker as my first boss and mentor.

Dale Lucht:

And we were using Shingijutsu at the time. George gave me the opportunity to make visits to Japan and see firsthand what was being done there. And so that was really my awakening. And then the second part of that awakening was they put me in a role of plant general manager, and so I actually got to lead the change.

Dale Lucht:

And following that, we were talking and said, “You know, these principles apply throughout the organization, not just the manufacturing floor.” So then I became Vice President of Distribution and began applying these same principles to distribution centers. Found out that worked, and then became Vice President of Supply Chain and began taking it to our supply chain partners, both upstream and downstream, and found that the same principles work because everything is a process, which really opened my eyes to how it's much bigger than manufacturing.

Early Experiences and Foundational Lessons

Mark Graban:

And your moves into other industries only further cemented that belief, I'm sure. But I'd love to dig a little bit back into some of your early stuff. So if I heard you right, you started your career at a different company and then moved to HON, is that right?

Dale Lucht:

That is correct. I've worked for five companies in my career, three of them manufacturing. HON was the second company, and then I also led transformations in healthcare and in financial services and banking.

Mark Graban:

And at that first company–not to pick on them, because this is a common situation–when you mentioned that they were using bits and pieces, I'm curious: what was your function, which bits and pieces did you see, and what led you to think, “Oh, there's got to be more than this?”

Dale Lucht:

Well, we were a manufacturing company making process control equipment, so a large machine shop. And so we were using things like group technology, reducing setup time, and trying to build flow into the process. But at the same time, it was, “Oh, this sounds like a neat tool. Let's apply that.” “Oh, here's another tool we could use.” And it wasn't as integrated as I was finding as I read more about and learned more about the Toyota Production System.

Mark Graban:

So some of that outside exposure or exposure to outside ideas helped you think, “Okay, well, let's find a place where that's being explored more fully.”

Dale Lucht:

Absolutely. And at the time, I was involved in professional organizations like APICS and ASQ and was starting to see some of the work that other organizations were doing.

Mark Graban:

So, I mean, when you talk about a lineage of, you know, great mentors–George, Shingijutsu–all, you know, legendary names, many legendary names within Shingijutsu circles. But, I mean, you know, Shingijutsu, maybe unfairly so–so correct me on this–you know, they're very known for the week-long kaizen event.

Dale Lucht:

Absolutely.

Mark Graban:

But there was… I mean, so I'm curious, you know, your experiences with that. And was there more than that? Because I know a little bit–I don't have the firsthand exposure–but to be maybe more fair and complete, they coached leaders. There was more going on than just event after event, I presume.

Dale Lucht:

Absolutely. And as their consultants would be at a plant–so when I, for example, when I was a plant general manager–they would spend time with the teams doing the kaizen event work, but they would also spend time with me as a leader, saying, “Okay, here's the direction we want you to take the organization before we come back in three months. Here are some of the difficulties we're seeing and some of the things that perhaps you can change in your organization.” And so they never left without giving me homework.

Mark Graban:

Well, what's an example of that homework?

Dale Lucht:

The homework might be, “You're bringing the parts to the line on a conveyor system. How can we shorten the distance that those parts travel by perhaps doing it manually?” And as an engineer who had spent a lot of time putting together the conveyor systems, this was a real challenge to get my head around. But it was things like that and their look at the elemental work. And what really helped was going to Japan and seeing some things like the chaku-chaku lines and how parts were positioned as they came to a workstation to really take the motion out of the work.

Dale Lucht:

And as an industrial engineer by background, that all made sense.

Mark Graban:

And refresh my memory, and people might not know this term, chaku-chaku. Is that where, you know, it's kind of the process of unloading and loading the parts? Or am I thinking of something else?

Dale Lucht:

Well, it's a process of linking production steps side by side. And as the part comes off of one line, getting it in position so it easily goes into the next step of the line. So it's the close proximity, it's how the parts are positioned. And of course, you're building quality steps into the line as well with different types of poka-yokes or andons as you go.

Mark Graban:

Because that might… I think I'm picturing correctly, of like a fairly tight U-shaped cell.

Dale Lucht:

Yes.

Mark Graban:

These machines are kind of right next to each other, minimal–if not, you know, maybe just one piece of WIP. And I mean, this is getting into the weeds, but I'm an IE, and I remember back to this detail level of, like, the reason why a U-shaped cell usually goes counter-clockwise has to do with that chaku-chaku in that motion, right?

Dale Lucht:

That is correct.

Mark Graban:

Because what I remember was, that way, unloading with your left hand if you're right-handed takes less dexterity compared to loading with your right hand. And that's why you end up kind of moving to your left, right?

Dale Lucht:

That is correct. And then with the U-shaped cell, it also makes it easier as your takt times change to combine jobs and modify the work content of each position on the line.

Leadership and Cultural Transformation

Mark Graban:

So fun to geek out on those industrial engineering and manufacturing details. But, you know, you tend not to find the same applications then in healthcare and other settings. So maybe, you know, let's talk about some of the things related to leadership and culture that are probably more transferable. I'm curious, either about things you remember learning from George or things you learned through… I'm guessing some of these mistakes. The “our” includes not just your two co-authors, Peter Barnett and Morgan Jones. There were probably mistakes. We all make mistakes, especially early on. Were there formative mistakes and/or lessons from George that you took with you into other settings?

Dale Lucht:

There were certainly a number of lessons, and we mentioned some of them in the book, but we list the nine lessons, and some of the ones that I learned early on were visibility and an obsession for simplicity. So the need for me as a GM to be on the plant floor, the need for me as a Vice President of Distribution to visit the DCs and be on the floor of the DCs. In manufacturing, when I was a GM, we took it to a pretty high level and said, “Okay, we're going to have our staff meeting table out on the plant floor.” When we have a staff meeting, it's literally on the plant floor, and if somebody's taking a break, they can sit in and listen to what we're talking about.

Dale Lucht:

We required everybody on my staff, including myself of course, to work four hours a month on the line. To really understand, we would rotate into different spots, and I must say that some of those times when we were on the line were some of the highest productivity days. Not because we were good, but because they wanted to see if we could step up the pace.

Mark Graban:

The team members challenging you. “We'll show you.” Yeah. And the structure of the book, the early part of the book I'm looking at here, it talks about those lessons, but sort of building upon the mistakes that are made that illustrate why the lesson in the principle is what it is. And there's one here written as “getting lost in process improvement and failing to see the bigger picture.” Just as one example I had highlighted. Could you kind of elaborate on that one for us when it comes to other related topics around purpose and alignment?

Dale Lucht:

Yeah. I would say, first of all, what we listed in the book and our learnings were from our personal experiences, our experiences as senior Shingo examiners to visit other companies and see what world-class companies were doing, and interviewing companies that we knew had adopted the leadership principles to get their thoughts. But back to your question as to getting lost in process improvement: that's where we all tend to start because that's some of the easiest parts of understanding the Lean or Toyota Production System principles. And so we start to look at how we take waste out, do value stream maps, and really look at how we improve the process and define what the process is.

Dale Lucht:

Many organizations, we found, see dramatic improvement in that first two to four years, and then they plateau. And unless they change their leadership focus, their leadership style, that's probably as good as it's going to get. The organizations that change tend to keep going. And it brought it to light when I was interviewing at Discover and I said, “Why do you want me to come in and be one of these people that coaches the executive team?” And the person I was interviewing with said, “Well, you know, we've seen this company is plateauing, and we've come to the conclusion that we need to change what we're doing as leaders, and we can't do that without some help and some people that have been through the process.”

Applying Lean Across Industries

Mark Graban:

Well, it's good they were open to that. And that was, I guess, industry three in the phases of your career.

Dale Lucht:

Yes.

Mark Graban:

So let's talk about the first transition point, I guess like you said, 2010, from manufacturing into healthcare. I'm curious where that interest or opportunity came from. As you know, I think Lean was becoming… there was a lot more interest in Lean in the late 2000s coming into healthcare. What prompted you to take that new opportunity?

Dale Lucht:

Well, I think it was curiosity and the belief that it could make a difference, and make a difference in an industry that really affects people's lives and their well-being. So it had sort of a higher value, if you will, as I thought my way through it. You know, if you look at my career, I started as an engineer and worked in quality and process improvement and did traditional industrial engineering type work. And then I moved into line management, doing it as a leader. And then the third phase of my career has been leading process improvement transformations in companies with the belief that it can be done in any industry.

Dale Lucht:

So that was really my first test of myself to say, “Can this be done in any industry?” And, yes, it could, as you well know.

Mark Graban:

So was that an opportunity that found you or something that you kind of proactively said, “Well, I'm going to go find an opportunity in healthcare?”

Dale Lucht:

It was a combination of both.

Dale Lucht:

And at the time I was looking for something different, and this was definitely something different and one that I was very pleased that I made the move to.

Mark Graban:

Did you see a similar progression in terms of… you talk about this evolution, I guess, from implementing Lean tools to focusing on process improvement, to focusing more on changing leadership styles. When you were starting in healthcare, did things sort of naturally have to go through that progression, or were you able to put together a different roadmap based on having seen that progression back in manufacturing?

Dale Lucht:

I don't know that I'd say it has to go through that progression. In fact, it probably works better with the leadership change coming first. However, we were following that typical progression when I moved to healthcare. We started with process improvement and then began working with leadership change and so forth as we moved forward. Fortunately, as well, in the area that I worked in, we also had some people that worked with leadership coaching as well that helped me really hone my skills in that area.

Mark Graban:

Because, I mean, this question of what you are working on, it depends a little bit on the mandate. And back to that question you asked at Discover, you know, “Why are you hiring me? What are you hoping to accomplish? What's the scope of the mandate?” Because there's a difference between improvement and transformation.

Dale Lucht:

Most organizations truly do start with improvement as opposed to transformation because, quite frankly, in a lot of cases they're looking at ways to become more efficient, take waste out of their system, reduce cost, and they're looking for a way to justify what they're doing. And so many times, organizations are looking at, “Okay, I'm going to invest in these coaches and this internal organization, so what's my payback?” And most organizations aren't willing just to take that leap. They're looking for constant feedback on the payback.

Dale Lucht:

But an organization that's going to make this work long-term will tend to look at it as a total transformation. And that's what I would advise people to look for in an organization. Are they really out to make that transformation?

Mark Graban:

And you know, about that time in 2010, there were a couple of fairly well-known transformations in healthcare that inspired others to go down that path. But yeah, I mean, there's something to be said for kind of an incremental, “prove things out” approach. I mean, you know, transformation is a big word that different people might define differently, right? Does transformation mean a lot of improvement, or does transformation really mean more of a reinvention?

Dale Lucht:

Well, transformation to me means that you've really changed the leadership focus of the organization, that you do have a purpose that's engaging people, and that leaders are following some of the points that we point out in the book: the nine lessons.

Mark Graban:

And so it's not just leadership styles, but, yeah, leadership purpose. And, you know, I'm skeptical of and have tried to not put myself in a position of something that's cost-oriented. You know, just speaking broadly, not every healthcare organization, but I've been to a number of them where senior leaders would say something to the effect of kind of complaining about the employees not being excited about Lean. And it doesn't take too many “whys”–and for those who are just listening, Dale was kind of leaning back and laughing at that, or smiling at least, in recognition of that–and it didn't take too many “whys” to really kind of figure out, like, well, people weren't excited about cost-cutting, which probably shouldn't have fooled anybody because that's really how Lean was being framed. And there are some long traditions of cost-cutting focus in healthcare.

Mark Graban:

So how do we find or develop the leaders that are focused on the more balanced approach of safety, quality, delivery, and cost, as a lot of people would frame it? Maybe even HON used that language, I'm guessing, SQDC?

Dale Lucht:

Well, it's… you know, again, the reason cost-cutting gets so threatening is it usually means reduction of people. And the way most individuals would look at that is it means I have to work harder, not smarter. I just have… I used to have these little gaps where I had time on my hands, and now it's a continuous flow of work. And that's really not the objective at all. But that's Lean, run amok, can lead you down that path.

Dale Lucht:

And so, you know, one of the things we tried to do at HON was every time we did a kaizen event or random improvement event, you had to have a specified number of quality improvements and safety improvements along the way so that, you know, you could say, “Okay, this is what's in it for the customer. This is what's in it for the member on the line.”

Dale Lucht:

And, but a lot of it, you know, boils down to really changing the role of the leader.

Mark Graban:

And avoiding the mistake of, yeah, using Lean to drive layoffs. I mean, were you ever part of an organization that took it in the other direction and kind of guaranteed no layoffs due to Lean, or were they just at least being careful?

Dale Lucht:

We never said no layoffs, but in most cases, we reinvested those heads. So if a line was able to reduce by two people, we would perhaps give them two engineers to help continue the improvement and make the work better. So the net would come out even or close to even. And so we wanted to continue to drive that improvement engine.

Mark Graban:

And part of, I mean, hopefully, there's a growth engine where you can redeploy people to growth.

Dale Lucht:

Absolutely. Yeah. That's what you hope all the way along.

Dale Lucht:

And you can spend time on education, development, and that type of thing. So suddenly you do have time for the training that you've been putting off.

Mark Graban:

So then, the third stage of your career, financial services, kind of a new environment, new opportunity to kind of prove out the transformation approach, the leadership approach. Tell us about that.

Dale Lucht:

Well, my role there was primarily in coaching the leaders in the transformation and helping them change their approach to their daily activity. And, you know, with a firm such as Discover, the process is usually either satisfying the customer through customer service or developing better systems. So a lot of work with your IT departments and developing Lean through there. So, you know, that work was different, but most of it was with leaders and helping leaders to see their new role as a leader.

The Leader as a Coach

Dale Lucht:

As a young manager, we tend to know that our role is to have the answers. People come to us for the answers. So as we progress in an organization, we tend to say that's still our role, to have the answers, only they're to bigger questions.

Dale Lucht:

And to have a leader understand that now their job is to set direction, to set strategy, and to coach others; to be able to ask questions to help their team solve their own problems. And, you know, the first time you take a leader out to do a floor walk and a daily production meeting or a customer service meeting, the first time the leader attends, they think, “Well, oh, I'll take that, I'll solve that problem for you.”

Dale Lucht:

And then it becomes a coaching process of, “No, you should have asked questions so that they better understand, and you can guide them as opposed to solving the problem for them.”

Mark Graban:

And can you think of moments where you've coached people through… I mean, you know, you talk about questions, and I think of Edgar Schein and Humble Inquiry. You know, that book and that approach has been popular. There's a difference between asking a question you don't know the answer to and thinking you know the answer, but asking questions that are trying to steer somebody to your answer, right?

Dale Lucht:

Yeah, you're absolutely right, Mark. And in our book, in the appendix, we provide what we call cards for each of the nine lessons. And it's meant to be something that you can have a card in your pocket, or whatever. And on one side it says, “How am I doing?” and you can evaluate the leader and the organization, but on the other side, we list common questions that you should ask about that lesson. And those are meant to help lead the individuals to form their own decisions and solve their problems and help you understand so that if you do have to get involved, you know when and how to do that.

Mark Graban:

There's sort of a rubric here to think about, even to self-evaluate where you are in a progression. So thinking of, like, choosing one here, Lesson Three, “Ideal results require ideal behaviors.” Level one includes, you know, for a leader, “traditional systems and metrics and a short-term focus.” Moving up to, in this case, level five, “KPIs for not just hitting the metric, but improvement goals. Creating an environment to align metrics.” I mean, it seems like a very helpful and useful thing for people to format or print out and carry around. One thing I wanted to ask before the story of the book is, you know, this emphasis on coaching. So I'm going to jump ahead to that. You know, the shift from being coached to being able to coach yourself… kind of talk about that transition, why that's important, when the timing might be right for that. Say, “I am qualified to enable and coach myself.”

Dale Lucht:

Well, you're on target. The book is divided into three parts. The first is the lessons. The second is about self and supported coaching. We find that most leaders need a coach or a mentor. It can be an internal coach, an external coach, or a mentor within the organization. And then once they've honed their skills–and in fact, as you look at those progressions on those cards, by the time you get to a four or five, most of the time it is the leader coaching someone else to develop those same skills. And so the third part then is how does the leader become a coach for their organization?

Mark Graban:

And is there an opportunity to practice coaching others by coaching yourself? Or do we learn more by coaching others and then apply it to ourselves? Or maybe it's interconnected.

Dale Lucht:

I think it's interconnected. I think first it's yourself and having your eyes open enough to be able to see yourself, and then learning how to coach others. But as they always say, you know, people watch a leader's feet and their hands, and not their mouth so much. And so where are you going? And, and a little bit, what are you saying? But they can't read the heart very well to see if it's really truthful.

Dale Lucht:

It's really truthful.

Mark Graban:

When you talk about, you know, starting with yourself and about coaching others around mistakes, a topic we've both written about in different ways, in your book and mine, you know, I think of going through the journey of, “How do I react to my own mistakes?” and using that as a practice ground, you know, to think about, “Well, how would I react to mistakes others make?” You know, do I beat myself up for doing something stupid, or can I kind of control that urge? And in fact, well, maybe in some ways, Karen Ross would coach me and say, “Well, you know, talk to yourself”–I think this is from Karen–“the way you would talk to others.” Like you might not say to somebody else, “You idiot, why'd you do that?” But our self-talk or attempt at self-coaching might not be as good. I'm curious if you have any experiences along those lines.

Dale Lucht:

Well, I think as one of my coaches once said to me, you know, in a failed situation or a less-than-optimal situation is, “What did you learn from that?” And so that's become part of what I always ask myself is, “What did I learn from that? What would I do differently the next time?” And sometimes you see it yourself, and other times you need a mentor or a coach to help you see it because it's not always obvious to yourself, especially when you're making the transformation and you're young in the process.

About the Book: “Don't Repeat Our Mistakes”

Mark Graban:

So I want to talk… let's dive in and talk about the book. Again, it's Don't Repeat Our Mistakes: Nine Lessons for Leaders Championing Cultural Transformations. Dale Lucht joining us today, Morgan Jones, Peter Barnett, co-authors of that book, available now. I'd love to hear the origin story for the book and in particular the title, because some people just kind of cringe or balk or react to the word “mistakes” the way some people react to the word “problems.” You know, we talk about problems a lot in TPS and Lean. How… well, maybe, you know, just first off, the general story of how the book came to be, and maybe I'll follow up about the title if that doesn't flow from the origin.

Dale Lucht:

Well, Peter and Morgan and I have met each other professionally on a number of paths and decided to collaborate on the book. Peter and I worked together in coaching leaders at Discover and had known each other before that, and we knew Morgan as well through the Shingo Prize. Primarily, we are all senior examiners and team leaders with the Shingo Prize. So as we would go on team visits, we got to know each other and kept in touch with each other. And through that, we decided that there were some lessons that we needed to write about, and specifically what we had learned in coaching others and observed.

Dale Lucht:

And so we wanted to leave a legacy in what we had learned in observing, leading, and coaching. I recently retired from the professional world and so I had a little time on my hands. We worked together to pull this through. We tried to capture what we've learned and what we observed in world-class companies. Then we did a number of interviews with leaders as we did our research to start the book, to begin with, to get their ideas, and then secondly, to bounce some of these off of them, to refine them and get their input. So we've been working on it for a couple of years, and it's been available in the press for about six weeks now.

Mark Graban:

Well, congrats on the launch and getting it over the finish line. There's always the risk that you want to tinker with the book forever instead.

Dale Lucht:

Yes, there is. One of the things that we decided early on as well is our purpose with the book is to talk about the lessons and talk about coaching. So we decided early on that any income or any profit, if you will, from the book would all go to a charity. And we settled on the Michael J. Fox Foundation. So we're donating all proceeds that we would have to that because all of us have had families that have been touched with Parkinson's disease and felt that this was a worthy cause.

Dale Lucht:

That in addition to our legacy with the book, we could perhaps make at least a small contribution to that cause.

Mark Graban:

Well, that's nice. That's nice to hear. So thank you for doing that. And you know, one of the things that's challenging… writing a book is hard, but agreeing on a title is difficult. Did the title come first, or did that come later in the process with some debate and discussion around, you know, what's so hard to objectively decide what's best? But I'm not questioning the title, I'm just curious.

Dale Lucht:

So it really came… it did not come at the beginning, and it really came as we were interviewing leaders and then as we were taking a very crude manuscript and sharing it with a few leaders to get their thoughts. More than one of them came back to us and said, “Hey, what I'd really like to hear is… you've talked about the good side of what happens with all of these, but what happens if you don't do it that way?” And I'm sure you've witnessed it. And we said, “You know, that's a good observation.” We can all write about things we've seen and experienced. And so we tried to throw in a little bit with each of the nine lessons of, “And here's what we've seen if you misinterpret this lesson.”

Mark Graban:

As you were interviewing people, different leaders, were they willing to talk to you because they were generally more forthcoming about mistakes, or did you have to kind of draw that out of people? Because it is more fun to talk about the successes and the things we did well.

Dale Lucht:

Well, in many cases, they said, “Hey, here's one you can write about, but don't use my name.”

Mark Graban:

That… yeah, that helps people feel safer to share.

Dale Lucht:

And so we honored that, respected that. So most of the mistakes you'll see will have Peter, Morgan, or Dale's name.

Mark Graban:

You're willing to put your name on at least some of them.

Dale Lucht:

There are a few anonymous ones in there.

Mark Graban:

And there may have been overlap. When you say “our mistakes,” some of those mistakes were probably shared experiences.

Dale Lucht:

Absolutely. In fact, most of them tend to be a shared experience where, as we would talk through it, we'd say, “Here's a mistake I think fits well with this lesson,” and maybe I'd bring it forward. And Peter and Morgan would say, “Oh, yeah, the same thing happened to me. Here's how I would frame it.” So, yes, in many cases, we experienced the same shortcomings, especially with coaching leaders and that type of thing, and taking it beyond the process improvement to a true leadership transformation.

Mark Graban:

And by the way, thank you for asking me to write the foreword for the book.

Dale Lucht:

Thank you for doing it.

Mark Graban:

And, you know, publishing… you know, the value stream can be kind of slow. And, you know, Morgan and I had talked about that, and it takes time for a book to make it through publishing. And then, you know, you had sent this to me and I'm flipping through and it says, “We all make mistakes. What matters is learning from them.” And I'm like, “Oh, that guy's onto something.” Being a space cadet, I'm like, “Oh, yeah, yeah, yeah, I wrote that.” But happy to recommend the book because I think that willingness, as you and others demonstrate, that willingness to be forthcoming about acknowledging, “Hey, you know, we're not perfect, we made mistakes,” but there are the lessons and, you know, reframing mistakes as a foundation for learning instead of something to be ashamed of, you know, that was something I wanted to help celebrate.

Dale Lucht:

Well, and what we found is most leaders that have been through the process are very humble about it and, you know, willing to talk about their mistakes. When you read many, many of the books that have been written about it, about somebody's journey, they're more than willing to talk about their mistakes. And it's done in a very humble manner. But to your point, it's, “What did I learn from that, and what can I do different? How would I coach somebody to do it differently?” So I've seen those mistakes. Okay. When I'm coaching leaders, how do I keep them from stepping on the same landmine?

Becoming an Active Champion

Mark Graban:

So think about, you know, kind of the transition, you know, I think as you had framed it, from kind of sponsoring Lean or being kind of a distant supporter to becoming more of an active champion. So if somebody listening today wants to take a step in that direction, what should they consider? What would you recommend to them? Maybe as a better first question, how do you define that more active champion?

Dale Lucht:

Well, I think, first of all, to look at the nine lessons and then look at the one-through-five cards that we provide and do a self-evaluation of where am I today and where is my organization? And is the organization ahead of me or behind me in those rankings? And so that's step one. And once you understand the lessons, then getting a coach that can be internal, external, or a peer mentor in the organization that you trust for feedback. And as we work with leaders and coaching, it's overwhelming to try and do all nine lessons at the same time. So we usually say, “Okay, which one are we going to work on this 30 days or this 60 days?” Where are we going to try and move the needle in the near term? And so if on that rating I'm a one in the area of simplicity, then, okay, how do I get to be a two or a three or a four in a short period of time? Okay, now I've moved the needle up in simplicity, and now I want to work on my role as a leader. I want to work on visibility and picking short-term goals, using those cards to where you can say, “I want to move the ball one or two notches up, and then I'm going to go back and pick up one of the others and move it up.” Chock the wheels; don't slide backwards on that one.

Dale Lucht:

And then pick up another one.

Mark Graban:

So you've got those… back to the appendix again, those nine cards and those five levels lends itself to one of those spider diagrams that you could map out. In fact, there we go.

Overcoming Organizational Challenges

Mark Graban:

So there are a couple of other questions I wanted to ask before we wrap up, Dale. There are so many things we could talk about. Sometimes the challenge is, in the moment, which question… we can't get to them all. But you talked about being hired in at Discover with this mandate to coach senior leaders, and you had earned that through your time as a senior leader and coaching people through other industries. I think a lot of times people don't have that kind of express mandate or permission to coach. And I think one thing a listener might be in a position of, if they're in the middle of an organization, might be, “Well, is there anything I can do to try to earn the trust or gain the permission to coach upward if it's not being explicitly invited?”

Dale Lucht:

That's a tough one. And it's really a matter of trying to get the ear of the senior leaders in that case. Because in most situations where that is the case, they are more interested in cost reduction and process improvement and saying, “Okay, this transformation is an engineering transformation, not a cultural transformation.” It's sort of like, “Fix them, but don't worry about me.”

Dale Lucht:

And so what you've got to do is find that sensitive ear, that sponsor in the organization, and try and get the attention in that area. And that's not always an easy thing to do. And so many times what we see when an organization that really does get it goes backwards, it's with a change in CEO, it's with a change in leadership. And suddenly the prior leader believed in it, but this leader says, “Okay, no, I want you to improve quality and reduce cost.”

Mark Graban:

Are there any lessons learned that you've accumulated along the way of how to prevent that back… that shift when there's a change in leadership? Is that a matter of trying to influence and educate the board? I've heard that come up as a topic sometimes, especially in healthcare.

Dale Lucht:

That would help. But it's really a matter of gaining the awareness and saying, “As a leader, I like this new way of leading. I like empowering my team. I like having time to spend on strategy and culture as opposed to solving day-to-day problems. And I like having a regular routine as opposed to, ‘Let's see which fire comes up that I've got to stomp out today.'”

Dale Lucht:

So what I found is leaders have got to reach that tipping point where it's no longer a chore to change the culture, but they're seeing the value and the rewards of changing the culture.

Dale Lucht:

And until you reach that tipping point, it can be a struggle.

Mark Graban:

And I think one of the challenges is those different statements that you made about, “I like engaging people,” “I like being able to think about strategy.” Not everybody would agree with those statements. They may, whether they admit it or not, like the reactive, firefighting, swooping-in approach. They may feel pride, you know, in as much as we'd say frontline employees want to have pride in their work and find pride in participating in improvement, you know, senior leaders may have their own things that they enjoy, whether they'll admit it or not. And I guess the question is, can they change, or will the organization invite them to go someplace else where those other joys are welcome?

Dale Lucht:

Still, I think quite bluntly, they should look for another opportunity within the organization because they've followed the Peter principle, and they're no longer firefighters, they're arsonists, perhaps.

Mark Graban:

And to think about systemic causes, to be fair to people, I've seen a lot of cases in a broad stretch of healthcare organizations where the director is doing manager-level work, the vice president's doing director-level work, because at some point they maybe got promoted to a level where somebody wasn't coaching them on how to shift from being a director to a vice president. So they keep being a director. And that can cause different challenges. And you know, I guess a lot of it does come back to coaching. Like giving someone a new job title doesn't mean they can flip a light switch and become a different leader.

Dale Lucht:

Well, like I said earlier, if their impression is, “I just solve bigger problems now,” then we have an issue. And a lot of it goes back to developing a routine, developing that leader standard work that says, “I'm going to devote time to these specific topics.” And when you talk to some senior leaders, they say, “Well, I don't know what I'm going to be doing today till I get there and then it'll happen.” And there will always be some of that, and there will always be those problems that crop up. But there has to be a routine for leaders just as much as there's a routine on the plant floor or in the physician office or wherever.

The Power of Curiosity

Mark Graban:

So maybe one final question here. You know, looking at the nine lessons, I'm going to be curious about curiosity, because Lesson Eight is on curiosity. Because some of the lessons… you know, the language and the perspective from the Shingo framework comes through very clearly on a lot of this. And so how would you kind of give us a nutshell of why curiosity is such an important trait?

Dale Lucht:

Well, it really boils down to the culture of rewarding experimentation and trying new methods, while at the same time keeping the customer or the patient isolated from the changes that you're making. And that's a balancing act. Certainly, you don't want to just make a change that's going to affect a patient or affect your customer. So you have to set up some sort of borders, but you want to reward that experimentation. A story that I would relate is when I first joined HON, we were struggling with the color matching on stained wood desks and cabinets and so forth.

Dale Lucht:

And we had no trouble with color matching when we spray-painted a metal product. But wood, being a natural subject, we would have some struggles. So we were measuring the paint electronically with an electronic meter, and we could get it right on. So we started to experiment and say, “Well, can we do the same thing with wood?” And while there was more variability, we found that if you sample enough spots, you can take an average of those samples and say, “Okay, this is the right color.” Even though the substrate for the cherry or oak or walnut or mahogany was slightly different, we were able to adjust the stain to get to that color. And we were able to prove that electronically. “This one matches, this one doesn't match our standard for that color.” And they had to match because a person might order a desk one year and a year later order a bookcase to go with it, and they wanted them to look the same.

Mark Graban:

And you don't want the color to creep very gradually over time, even.

Dale Lucht:

Yeah, yeah. The only tricky part of that is wood does, through sunlight, fade slightly. And so you'd have to explain that leap of faith that, “Well, wait a year, they're going to match eventually, because this one's where that one started.”

Mark Graban:

Or do you get to the point where you say, “Well, I need to buy something that matches a two-year-old desk?”

Dale Lucht:

We never reached that point.

Mark Graban:

But no, there are so many variables. And like you said, you know, with natural products, this isn't plastic, where you can…

Dale Lucht:

Right. But we could apply the scientific process of measurement. So rather than just having someone hold up a sample board and say, “That's close enough,” we knew how much was close enough and how much wasn't close enough.

Dale Lucht:

We knew how much was close enough and how much wasn't close enough.

Mark Graban:

So just one other last follow-up question. When you talk about curiosity and the willingness to experiment, you know, I forget who I heard say this originally, I wish I could be citing the right person, but if you know absolutely what the outcome of an experiment is going to be, it's not an experiment. So I think experiments open up the possibility of failure. Where does curiosity or other leadership traits help us react more constructively when an experiment doesn't go the way we predicted?

Dale Lucht:

Well, one of the things we bring out is, is risk-taking rewarded or punished in the organization? And do you have a system in place for your team to collaborate with that risk-taking? And if you do, the system is working and you have a curious organization.

Conclusion

Mark Graban:

Well, I think a lot of things flow downhill. Curious leaders lead to a curious organization. So I want to thank you again, Dale, for being here on behalf of your co-authors, Morgan Jones and Peter Barnett. The book again… [accidentally hits mute] Speaking of mistakes… Don't Repeat Our Mistakes. I bumped my microphone and I guess I hit the mute button on it. Don't Repeat Our Mistakes: Nine Lessons for Leaders Championing Cultural Transformations, available now. It's from Productivity Press. I'll make sure there are links in the show notes. So, Dale, again, congratulations and thank you for a good conversation today.

Dale Lucht:

And thank you, Mark, for the opportunity to hold this discussion with you and your listeners.

Mark Graban:

Sure thing. Thanks.

Please scroll down (or click) to post a comment. Connect with me on LinkedIn.

Let’s build a culture of continuous improvement and psychological safety—together. If you're a leader aiming for lasting change (not just more projects), I help organizations:

- Engage people at all levels in sustainable improvement

- Shift from fear of mistakes to learning from them

- Apply Lean thinking in practical, people-centered ways

Interested in coaching or a keynote talk? Let’s talk.

Join me for a Lean Healthcare Accelerator Trip to Japan! Learn More