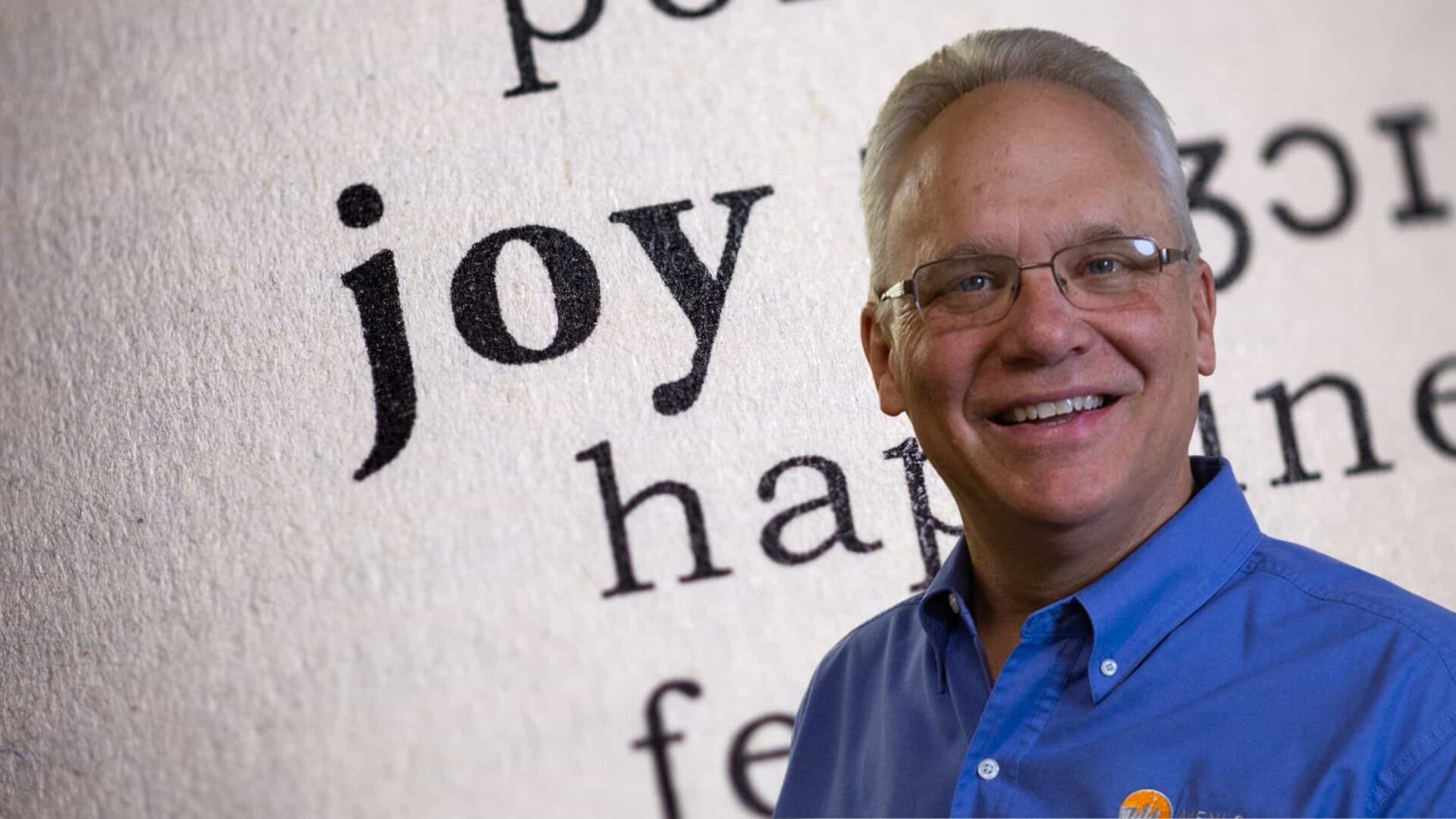

My guest for Episode #448 of the Lean Blog Interviews Podcast is Rich Sheridan, co-founder, CEO and “Chief Storyteller” of Menlo Innovations, a software and IT consulting firm that has earned numerous awards and press coverage for its innovative and positive workplace culture.

He's a returning guest from Episode 189 back in 2014 — the same year that I had a chance to visit the Menlo Innovations office.

We talked then about his first book Joy, Inc.: How We Built a Workplace People Love.

His latest book, published in 2019, is Chief Joy Officer: How Great Leaders Elevate Human Energy and Eliminate Fear.

Rich is giving a keynote talk, “Lead With Joy and Watch Your Team Fly!”, at the Michigan Lean Consortium annual conference, being held August 10-11 in Traverse City. I'll be there and I hope you'll join us.

Today, We Discuss Topics And Questions Including:

- For those who didn't hear the first episode, how would you summarize “The Menlo Way”? And how has “the Menlo Way” evolved over the past 8 years?

- Why is “eliminating fear” so important and what drains joy from the workplace?

- “Tired programmers make bad software”

- Sustainable work pace

- Paired work – Erika and Lisa

- Individual performance reviews?

- “We've eliminated bosses” — nobody to review you, the team gives feedback, develops growth plan

- “Let's run the experiment”

- Toyota talks about the need for humble leaders — why is humility such an important trait? Do you hire for humility or try to screen out those without much humility?

- No longer say “we hire for culture fit”

- “Not an interview, an audition”

- Leadership lessons from the pandemic- 4 blog posts

- In “Chief Joy Officer” you write about the proverbial “mask” that leaders feel pressured to wear… masking how we really feel. Were you able to be your authentic whole self at work, fears and all, during the early stages of the pandemic?

- “Scared and panicked” – was it OK to share that with the team?

- “They're all adapting” – as a result of everything we've been doing for 19 years

The podcast is sponsored by Stiles Associates, now in their 30th year of business. They are the go-to Lean recruiting firm serving the manufacturing, private equity, and healthcare industries. Learn more.

This podcast is part of the #LeanCommunicators network.

Watch the episode here

Listen to the podcast here

Rich Sheridan, CEO Of Menlo Innovations, On Eliminating Fear And Increasing Joy In Work

It is episode 448 for June 22nd, 2022. My guest is Rich Sheridan. He is Cofounder, CEO, and Chief Storyteller at Menlo Innovations, a software and IT consulting firm based in Ann Arbor, Michigan. They've earned numerous awards and a lot of press coverage for their innovative and positive workplace culture. Rich, you might realize, is a returning guest. He was here in Episode 189 back in 2014. That was the same month, January 2014, when I had the chance to visit the Menlo Innovations Office. Back then, we talked about his first book which was titled Joy, Inc.: How We Built a Workplace People Love. His latest book published in 2019 is Chief Joy Officer: How Great Leaders Elevate Human Energy and Eliminate Fear. Before I tell you a little bit more, Rich, welcome back to the show. How are you?

Thanks, Mark. It's almost like a time capsule here thinking back to January 2014 and how much has happened since then.

I'm almost embarrassed. I've known the book has been out for a while. I wanted to have you on. I should have reached out sooner, but I guess pandemic time and everything that's been in the way. I see your background. You're still in the same office space, right?

We are, yeah. Although for a little bit more, we're going to be moving. We'll be leaving our wonderful space that's been our home for the last few years and going on a new space adventure.

We'll have a chance to learn more about how the business has evolved and how the practices at Menlo have evolved. First, I want to tell you a little bit about the Michigan Lean Consortium Annual Conference. It's going to be held on August 10 and 11, 2022 in Traverse City, Michigan. You can learn more at MichiganLean.org. The one reason I mentioned that is that Rich is going to be one of the keynote speakers. He's going to be giving a talk titled Lead With Joy and Watch Your Team Fly. Again, I'll encourage people to go check out the Michigan Lean Consortium event.

If you haven't heard it, you can get a deeper dive into this with Rich back in episode 189, but maybe just a quick synopsis for those who are hearing about you for the first time, Rich. How do you define the Menlo Way? I'm curious, has the Menlo Way evolved in the eight years since we've talked? Has it changed a lot or is it a bedrock that remains consistent even if circumstances about the business do change?

The Menlo Way draws from a lot of different sources. Quite frankly, that's why you and I got connected so long ago because we absolutely draw from lean thinking, agile thinking, project management institute, systems thinking, positive organizational, and psychology thinking. I would say if you came in now and saw Menlo in its current form, there certainly have been adjustments made largely due to the pandemic as opposed to we fundamentally change the process. You would still be able to see all the same elements, spirit, and energy behind the process.

I'm sure we'll talk about in our time together, there were some severe adaptations we had to make that were very different from our first nineteen years. Just to give the listeners a little bit of insight into our history. We celebrated our 21st birthday as a company. We joke that it's now legal for us to drink. The elements of the Menlo Ways, as Simon Sinek would say, start with our why. Why do we exist? Why do we believe? Why do we want to end human suffering in the world as it relates to technology?

The more positive bend on that is, we want to return joy to software development. I believe joy has been missing for a long time in our industry. Quite frankly, it was missing for me personally. When people come, they're like, “How did you think of this? It was fifteen years of pain in my own personal career when I realized there's got to be a better way of doing things.

For us, it's an experimental mindset. I think Mike Rother is very proud of us in terms of how we do this. We're probably not quite as formal as Mike would like us to be, and I appreciate always Mike's thinking on this subject. One of the more common phrases here at Menlo is, “Let's run the experiment.” That's where a lot of the experimentations come from along the way.

Lots of experiments and new things given your previous experiences and what unfortunately might be happening at other companies. When you talk about returning joy, what are some of the main things that drain the joy out of people? You talk a lot about eliminating fear. Is that one of the main causes of this loss of joy? Are there other things that suck the joy out of people?

There's no doubt that if I were to write the opposite book of Joy, Inc. it would be called Fear, Inc. The way the industry or software teams are typically organized ends up in a high hero, high overtime type of environment. You have individuals, towers of knowledge as we call them, that know everything about a particular subsystem and nobody else knows what they know. The only way to scale a hero-based system is over time. Our fundamental belief is that tired programmers make bad software. We don't want to make bad software.

There's a scaling issue in software teams where we scale the individual rather than have a process and a people process that scales, which is probably the miraculous thing we've accomplished. We are able to do something that most people say there's a law against called Brooks's Law. They say, “We can't do what you suggest you're doing, Rich. Obviously, we've disproved it because we have.”

The main issue with software teams is scaling individuals rather than the processes. Share on XIf a project here is behind and it needs to go faster, we add more people. That's an easy thing to say. As we get into the details of how we work, it's fundamental to the process we use here. Just to give you a little bit of a peek into that, everyone here works two to a computer. Two people, one computer, sharing a keyboard and a mouse collaborating on the same task at the same time. This isn't, “Come help me with my work.” This is our work done together.

Those pairs systematically switch at least every five days. We have no one person on the team that is a singular tower of knowledge about any one particular point because they are having to share their knowledge with each other through this paired work. The delightful thing is, let's say, four people were working on a project for a few months and they're switching their pairs every week. You get three good combinations of people. We'll probably bring others in from time to time to cover vacations, outs, and that sort of thing.

When the customer comes and says, “Something happened in our business. We need you to go twice as fast.” We'll bring four more people in, pair them with the original four, and suddenly, within a couple of weeks, we have a team that is producing twice the output of the original team at twice the size with the same work schedule. We tend to adhere to a pretty strict 40-hour-a-week work schedule. No weekends, no overtime, no denying of vacation requests.

I think that's where the fear creeps in a lot of organizations when the boss stops by and says, “How's it going? How's that project you're working on? Are you coming in this weekend? You're not thinking of taking a vacation next week, are you? We're pretty close to the deadline.” Of course, fear starts to rise and individual pressure mounts.

Here, we don't have that. We work on hard projects, long projects, and complex projects. Our belief is, you want to create, as Kent Beck said in his original book on this topic, Extreme Programming Explained, a sustainable work pace. Software projects, especially these days, are often very big, very long, and require a lot of people. If you don't have a sustainable work pace, you're going to get to a certain point where your team burns out. They're just tired and now they're not bringing their brains in to work with them every day.

It's interesting you mentioned a sustainable work pace. That makes me think of Toyota. When I used to live in Texas and I would bring healthcare people into the Toyota Truck Plant in San Antonio, they would see a sustainable work pace. For people who had never been in a factory before, they're not sure what to expect. Maybe because of the word lean, they may picture that people are going to be frantically running around. That's not the case. It's a sustainable work pace because there are good systems that support the people who need that type of work. I'm sure people would see the same thing at Menlo.

A lot of our system, as you can easily imagine, has to do with how we manage the workflow here. How do we break the work down into achievable chunks so that we can give people a chance to go to work and get meaningful things done? How do we keep their focus on a single task rather than the traditional environment of multitasking, which isn't humanly possible? The thrashing that occurs as you switch from one thing to another. If you go home after long days and you feel like, “I worked hard and long today but I got nothing done.” The ability to go to work and get meaningful things done is probably one of the most joyful aspects of our system.

You mentioned the paired work and Kent Beck. He's associated with that. In Extreme Programming, we think of paired programming. As you write about it in the new book, there's this broader paired work that's taking place. It just occurred to me. I've gone to your website. I downloaded the free chapter of Chief Joy Officer. I got an email that came back. I noticed there was “we” language, and it was signed Erica and Lisa paired work even in this marketing or public relations function. It's interesting to see.

Erica and Lisa like to take vacations, too. They both have families. No singular dependence on an individual. Every organization I was part of before always had these towers, heroes, and people who were specific to one particular thing. When they went on vacation, some part of the process stopped. My co-founder James and I often joke, imagine a Toyota plant where there's one guy in charge of putting doors on the cars. He takes a two-week vacation and everybody's looking around the plant. They're like, “Why are all these cars missing their doors? Why are all these doors stacked up over there?” They're like, “Mark went on vacation and he's in charge of doors. We can't do doors this week. We want to keep everybody else busy so we're going to keep building cars. When Mark comes back, he's going to be a little busy because he's got about 10,000 doors to install.” It sounds silly. You'd see it in a plant and you'd be like, “No, you can't organize your plant that way. That's the dumbest thing I ever saw.” You then go into offices and they're all organized like that.

At a lot of companies, people view their job and the work they do. There's the “I” and the “me” language. When there's fear, there's job security and people identifying with their work. They'd say, “Rich can't get rid of me.” For people to share that responsibility, it probably requires you and other leaders to eliminate the fear that might cause all sorts of dysfunction.

Let's talk about where that fear rubber hits the road. Let's say you're in an organization that has great posters on the wall and inspiring speeches from leaders about teamwork, collaboration, and trust. Yet, there comes that magical day in December when you sit down in your boss' office, the door closes, and you have your annual performance review. Your boss says, “Let's talk about your individual performance.” Right then and there, all the world of posters, inspiring speeches, language, values, and all that stuff about teamwork, collaboration, and trust collapses in on itself.

When it comes to my job, my position, my level, my pay rate, and my ability to even keep my job, it's clear in that discussion, “That other stuff, that's rhetoric. When we're down to the things that most matter to you, we're going to be talking about your individual performance.” That doesn't even make sense in a team-based environment to talk about.

Have you eliminated those individual performance reviews or do you just give them less weight?

It's even weirder than that. We'll go down a lot of rabbit holes. We've eliminated bosses. We've never had any bosses here. There would be no one for you to sit down and have your annual performance review with even if we did have such a system. The team devised the system by which people get feedback, develop a growth plan, and ultimately get raises and promotions.

One of the delightful things that we've reinvented during the pandemic is because we've always had a system like this, it got a lot better in the last couple of years. We named the project Prosperity. I gave the team the full freedom to do whatever they want to do in this. I told them, “Do not make this process about raises and promotions. Make it about the personal growth of people, and the raises and promotions will follow.” What they devised is so beautiful. We do tours of it. People can come and take a free tour of what we call our Prosperity process about how we give feedback to team members in order to grow them.

Here's the weird thing about every one of our people's practices. We want you to succeed. I know that sounds silly, but think of how many interview processes are set up to try and get people to fail. Our interview is exactly the opposite. We give you hints. We give you explicit instructions. “This is how you succeed here.” The same instructions we give you during the interview are the same ones we're going to give you when we're onboarding you and when you're growing here. Make your peer partner look good. Support the person sitting next to you. Be a good kindergartner. Play well with others and collaborate. It's not just a poster on the wall, but it's actually how we work every single day.

You call that weird. I wouldn't call it weird. I think it's unusual in a good way to eliminate those annual performance reviews. I don't know if this is becoming trendy again. I've seen a couple of articles this year. I'm going to write probably a blog post about this soon about companies or people who are advocating getting rid of the annual performance review.

It makes me think back to W. Edwards Deming who said, “In no uncertain terms, eliminate the annual performance review.” He wasn't saying, “Don't develop people. Don't give them feedback.” It was meant to be a more continual process. What you were saying makes me think of a different Deming-ism. He would say, “The role of the manager is not to judge through annual reviews. The role of a manager is to help people succeed.”

It's funny. I found out after I'd written the book because I'd always been a big fan of Deming. It's probably no surprise to you. I find out that Deming himself used the word joy a lot. It was fascinating to me. In fact, in Chapter 10 of Chief Joy Officer, I used a Deming quote as an epitaph. It says, “Management's overall aim should be to create a system everyone may take joy in their work.” If there was one phrase from Deming that describes our intention in terms of creating Menlo, that is it.

Team leaders should always aim to create a system where everyone can take joy in their work. Share on XI love that. Dr. Deming would write about what he called the Forces of Destruction that drain joy from the workplace. I think that would include annual reviews, targets, quotas, incentives, and the dysfunctions that come with those. When people come into a workplace like Menlo Innovations, they come in and they're as excited as they'll ever be. We want to make sure we don't let that drop. Dr. Deming would give that advice of, “Don't demoralize people. Don't let the Forces of Destruction, including fear get in the way of people having joy in their work.”

I used to say that onboarding is one of the worst HR practices ever invented. I used to say as a hiring manager, my old way of doing things and my job was to try and get you productive before I demoralize you, which is exactly what Deming is talking about. I always say the best day on a new job isn't the first day because that's often one of the worst days. It's like, “We're glad you're here, but we forgot to get a table, a desk, a chair, a computer, and an email address. That project you were so perfect for, we canceled it between the day you come. We don't know what to do with you, but here's this book that I wrote, Joy, Inc. You should sit in the conference room and read it.”

Seriously? Why is it that when people join, it feels like a surprise that you might have to teach them something? The pairing aspect of Menlo I'll say it as bluntly as I can trivializes onboarding because you're never alone. You're never more than a foot away from somebody who can answer the question that's on your mind. We encourage you to ask those questions. We encourage you to say, “I don't know.”

That's the sign of a healthy culture where people are willing and able to say, “I don't know.” They don't have the fear to go make something up where they're BS-ing you, or maybe even worse, BS-ing a customer.

It's funny we should be talking about this because right there, there's a poster that you can't read on the pillar. One of our bigger posters says, “It's okay to say I don't know.”

In a Fear, Inc. company, the dynamics are one where if you're a new employee, you're told, and it might often be subtle. If you have a new idea, “Shut up. You don't know how we do things here. You should absorb how we do it,” where in a Joy, Inc. company, people would feel free to speak up from their fresh perspectives to ask questions, make suggestions, and make things better.

That goes to a phrase here that they will learn very quickly. When somebody has an idea, the answer isn't, “We've never done it that way before. I think that's against policy. We tried that five years ago and it didn't work.” The answer is typically, “I don't know. Let's run the experiment and see what happens. You can sign up at least one other person to join you in that experiment.” The odds are that you're going to be able to try something new and see how it works. Also, the willingness to say, “That didn't work quite the way I was hoping. How could we make an adjustment?” That's why I think Mike Rother and Kata, it's the same spirit and energy behind that.

I think this is a common scenario. If somebody is skeptical about a change or an idea, you can say, “Let's run the experiment and see if it works.” There's a filter I often use of, “If the idea seems unlikely to physically hurt somebody, then let's go and run the experiment.”

I talk to a lot of people about this and they're like, “How do you trust people to run good experiments?” Number one, if you're building a team of people you don't trust, you might want a harder look at how you're building your team. The other thing is, call it managerially, we're going to come off the rails here, people are going to be sending free money out to customers because they think that's a good experiment. Do you really think people are going to do that?

If you are building a team of people you don't trust, you might want to look harder at how you are building your team. Share on XI'll say it's about us. People asked what's part of the Menlo magic. Part of it is people believe in what we do here. The people who join believe in the approach we're taking, why we take it, and what its purpose is. I would guess some of the reasons they can believe that is because we can explain it to them. We set reasonable, rational, and explainable expectations for people about how we work.

Nobody is going to come into Menlo and say, “I think we should stop that whole pairing. That's my experiment. Let's stop pairing for a week.” They would reasonably expect they would get, “No, we're not going to try that experiment.” Why? Because the expectations about the basics of how we work are pretty well set and understood. People might say, “Maybe we could do remote bearing. Maybe we don't have to be in a physical office together.” Generally speaking, rational human beings are going to behave rationally.

I've had similar conversations with a lot of healthcare leaders where they have an irrational fear, but that's not a good word. Nobody wants to be called irrational. We can think and ask what is that fear based on. In a baseline Fear, Inc. organization, employees have probably usually been conditioned to be too cautious. As we help them become experimentalists, we have to help them take more risks. I think it's unlikely that they're going to become super reckless. If anything, my fear would be people are still fearful. I'm using that word a lot. We're going to help them become experimentalists and that means eliminating fear for employees and leaders.

In a healthcare environment, I'm guessing one of the biggest fears is speaking up. Let's say speaking up to a doctor and figuring out, “What are the patterns we can use to encourage people to wash their hands?”

There's a lot of hierarchy and fear.

That's often where the fear comes in. Again, go back to that annual performance review. Ultimately, those forms typically come down to two checkboxes, only one of which is going to get checked. I'm pretty sure most people don't go into their annual performance review thinking, “I pretty much met expectations this year.” No, they're like, “I exceeded expectations. This is my year. This is going to be the big one.” The boss then says, “Only 3.7% of you can exceed expectations this year. You did it five years ago, so you got to wait for your turn.” Everywhere, we could start every Fear, Inc. lesson right out of how those boxes are getting checked.

To not get too sidetracked on this, you've triggered a memory. The last time I worked for a big company that did these annual performance reviews, the annual scale went up to a nine. My boss told me in the annual review, “I was giving you an 8, but then some vice president told me we can only give so many 8s, so we've bumped you down to a 7.” I think, “Why even tell me all that? I don't know how that was all helpful or motivating.”

I can imagine if Deming were in this conversation. He's like, “What are you doing giving a human being a number on a 0 to 10 scale? Come on. Seriously?” Here's a beautiful question, and this is why our team does all the work around giving feedback. How on earth would I know how you're doing here? I'm in a one-hour conversation with you right now. I'm not out there on the floor watching how Dan is doing in relationship to a customer. Do you know who is? His peer partner and next week's peer partner. Do you think the people you pair with every minute of every day, if they're well-coached in how to give feedback to people, what to watch for, and what our expectations are? Do you think they might be better equipped to give Dan some informative feedback about what it might take to grow to the next level?

I want to ask one other question when it comes to hiring. A lot of people talk about hiring for culture, hiring for attitude, and hiring for a fit that we can teach everything else. One thing you highlight is a word that's important to Toyota, and that's humility. I'm curious if you are interviewing in a way that looks for humility. Is it easier to find a lack of humility? How do you think about that?

It's very important because you can imagine. If two people are working together, “I've got an idea. It's got to be my idea and it's got to win,” it's not going to work here. Over time, the team won't want to work with you. If every time you have an argument and an idea, your way needs to work. What we try and coach people right from the moment of first contact is, “Help the person sitting with you succeed.” That is a subjugation of self, an expression of humility at that particular moment. We're teaching it right at the moment of first contact.

I used to say that we hired for culture fit. I don't say that anymore if you saw the variety of people we have gathered in this team. I kept watching the team we built and I kept reflecting on this hire for culture fit thing, and I thought, “There's some incongruity here. What is it?” I realized what we're doing is not hiring for culture fit. We're teaching our cultural expectations from the moment of first contact. If you teach reasonable rational ideas that can be explained and are visible, most people will respond possibly to that. I think the people we end up filtering out are the people who don't believe it. They'll say, “Whatever. Teamwork, collaboration, and trust. I know what they want. They want me to exert my authority over this person sitting next to me. That's how I get ahead here.”

We do an audition. We don't ask questions. We never ask questions during the interview process of the candidate, which is weird. It's not an interview, it's an audition. You come in. We pair you with another human being who's also interviewing and competing for the same position you are. We tell you, “Your job is to help the person sitting next to you succeed. Make your peer partner look good. Demonstrate good kindergarten skills.” You might suck at it for the first pairing. You may be terrible, nervous, and trying to prove something. We then pair you again with another person for another 20 minutes, and we do it 3 times.

Literally, when we review you, we decide whether we invite you back for a second interview. There are three Menlonians who watched you pair in three different pairings. The first person might say, “Thumbs down. No way. I saw terrible behavior.” The next person says, “It's doing okay.” The third person says, “Double thumbs up.” There's been an interesting set of almost humor around this. Some people would be like, “What if Mark was learning to fake it? Fake collaboration.” My co-founder James had a funny response. He says, “Can he fake it for 40 hours a week? I don't care if he's an ex-murderer in his off-time. As long as he could fake collaboration while he's here, that's awesome.”

The other part of it is, “Look at how quickly Mark adapted in just a couple of hours. Once we started setting clear expectations for Mark, he adapted.” That's the lesson I've learned in the last few years about human beings. We're incredibly adaptable creatures when you set out reasonable, clear, and rational expectations for people.

One other question about the interview dynamic. These people might be competing for a position. That competition seems different from what the culture would be like within Menlo. You described people rotating through these different pairs. Would you try to structure hirings where people are collaborating so they can both get hired beyond trying to make your paired partner look good?

I'm not sure I fully understand the question, but I could imagine it going in one direction of, is there collusion in the interview process like, “I'll make you look good and you make me look good?”

No, it wasn't that. Let me try again. If you have people pairing with each other and they know there's only one position, that drives a little competition. That would not be part of the daily culture within Menlo. I don't mean to be critical. I'm just trying to think through some of the dynamics.

Those are some of the simple human characteristics. We wouldn't do our mass interview process if there was only one position. It wouldn't be sensible to go through that amount of effort for just one open spot. We have other ways of bringing in singletons outside of the mass interview process. Maybe about a third of our team has come in that way. It is still the case that they understand that if there are 30 of them, we may only be opening positions for 4. Again, back to that humility piece you brought up earlier. Am I willing to say, even within the context of this interview, “I might not make it? That's okay. I'm going to come for the experience. I'm going to demonstrate the best version of myself as I can, and I'll leave it open to the whims of who showed up and how did I do that day.”

Every interview process, every one of them including ours, has strengths and weaknesses. We will miss good people from time to time and we'll bring on bad fits from time to time. That stuff has to be sorted out later. One of the things that people appreciate about our process and may be different from a lot of companies, at least the ones I used to work for, is you can try as many times as you like.

If people had a good experience and didn't get the job, how often did they come back again to try?

There's a famous story in Chief Joy Officer about one of our programmers, Scott, who's now been with us for probably close to ten years now in 2022. He failed the first time. He came back a year later and said, “I'd like to try again.” We're like, “Of course.” He made it through but just barely squeaked through. The last part of the process is what we call a three-week paid trial. Scott came in for three weeks, and at the end of the three weeks, the team was torn. They were seeing good things and they were seeing some concerning things. They went back to Scott and they did something very unusual. Teams in charge of this process get to decide this stuff.

They said, “Scott, we're not comfortable saying yes yet. We're also equally uncomfortable saying no and sending you away. Would you be willing to consider another three-week trial?” He's getting paid. It isn't like some torturous free internship. He's like, “Yeah, I don't have a job right now. Why not?” Week 1 and 2 of the second 3-week trial, he was still failing in important ways. He was failing to respond to the feedback we were getting.

He grabbed David in the middle of that second-week trial who was the guy he was paired with. He said, “David, I don't want to fail. Help me succeed.” David was like, “What can I do for you?” This isn't like, “No, I'm not going to let you trick the system.” It's like, “Tell me what you need and I'll help you.” All Scott said was, “You guys keep giving me feedback at the end of the day and the end of the week, and it's not actionable. I need it at the moment.”

The biggest challenge we had was Scott wouldn't think out loud. He'd go quiet and he'd be typing. He always had good answers. That's why the team was confounded. The rest of the time, he'd be sitting there. We're not sure if he likes being here. We're not sure he's engaged. We're not sure he's paying attention, but then every time he said something, it was clear that he was exactly paying attention. Every time Scott went quiet, David was like, “You're doing it over again.” He then started talking. The joke from his colleagues was we can't get Scott to shut up.

He was able to adapt. Scott is a very introverted person. Our team is filled with introverted people. We'd have to corner the market of extroverted programs for people. That's what we're requiring. I think the team will declare it easily. We couldn't handle an overwhelming number of extroverts on our team. It wouldn't work. This is a very introverted team.

What I hear you describing is teaching the culture. The culture is to get better at thinking out loud. That can be taught.

Ask questions and make sure we know what you're considering. Again, it gets back to, “What are we trying to accomplish? What's our goal here?” In a traditional organization, the goal might be, “I want to get a raise or I want to get a job.” Our goal is we want to create great software for our clients. It's caring. In Chapter 11 of Chief Joy Officer, I talk about how we care for the team. I love this epitaph from John Wooden, the famous coach from UCLA. He said, “I worry that business leaders are more interested in material gain than they are in having the patience to build up a strong organization. A strong organization starts with caring for their people.” There should be evidence of caring as often as possible.

A strong organization starts with caring for their people. There should be evidence of caring as often as possible. Share on XThat seems deeply connected to joy in Chief Joy Officer. You talk about letting people be their full authentic selves at work, caring for people, and celebrating them. I was going to ask you to talk a little bit about pandemic time adjustments. You write vividly about this idea of this proverbial mask that people wear in the workplace or that leaders might wear. The way we feel pressured to behave or present ourselves.

I'm curious thinking back to what you wrote about in these blog posts. March 2020 was when we were all trying to figure out what was happening. How long is it going to last? What does it mean? Not just for the business, but what does it mean as individuals? How was it for you to be your authentic whole self at work that might include all these fears and uncertainties for yourself, for Menlo, for our country, and for our world? How was it to navigate that?

I was scared and I was panicking when the pandemic hit because what we were being asked to do that week of March 16, 2020 was turn Menlo inside out, upside down, and go to the alternative universe or the inverted universe. You're going to take a team that has been shoulder to shoulder, closely collaborative. You're going to put them all in their individual home offices. You're going to take your high-tech anthropology practice, which is our go-to-the-Gemba team. They're not going to be able to go to the Gemba anymore because you can't get on airplanes. You wouldn't have a Gemba to go to anyways, because they're all home.

You're then going to take the guy who goes out and speaks about joy, take him off airplanes, and he doesn't get to meet people. By the way, these thousands of people who come and visit us, they can't do that anymore either. At that moment, I couldn't see a path out. It was like that image I have of Harry Houdini. It's like, shackle him up, put him in a straight jacket, put weights around his ankles, throw him in the ice cold water, and let's see if he can survive, and I thought there's no way.

At that moment, I honestly thought this was the end. I thought, “That's okay. You had nineteen years. It was a good run. You accomplished what you set out to do. Nothing to be ashamed of. You couldn't have anticipated this.” I remember there was one day when Erica was sitting near me. She's relatively new, so she didn't know me that well. I said, “Erica, what is today?” She said, “It's Tuesday.” I said, “No. What day is it?” She's like, “It's March 17th.” I said, “No. What day of the week is it?” She's like, “It's Tuesday.” She swings her head looking over at my co-founder like, “Did Rich just have a stroke or something?” James looks at her and says, “Don't worry about him. He's just panicking. He'll be fine.”

There was a turning point and it happened pretty quickly. I credit Molly for this. She's one of our senior high-tech anthropologists. We were trying to figure out how to do our first high-tech anthropology engagement in this pandemic world. We can't go on an airplane. We're going to have to do it all remotely. I'm thinking, “This will never work.” I'm not sharing these thoughts with the team. They're all in my head. I'm just screaming run-for-the-exits in my head. She goes, “This will be so exciting to figure out how to do this.” Right then and there, it was like this grand relief. Suddenly, I looked around as best as I could virtually, and I thought, “They're all adapting. This is your problem, not theirs. They're figuring out how to do this.”

It was at that moment when I realized all the things we had done for 19 years. The communication, the collaboration, the trust, the relationship, the focus on human energy, and the empathy we have for the people we serve and others. All of it was coming to bear on this unique situation we're in. In some ways, it dawned on me. Unbeknownst to me, we were building an organization that was going to be ready for this dramatic effect. Every bank account we had filled up with relationship dollars and joy versus fear, it was all paying off right then and there. It was a pretty cool moment.

That sounds like the culmination of all that effort to build whatever words come to mind, like resiliency, agility, and adaptability. It goes to show you can't force that. You can't use speech and say, “Everybody, go be nimble and be agile.” You built that culture and gave people the freedom to adapt.

Trust your team. That was a big lesson for me.

As you wrote about these blog posts, the shift to 100% remote, and then starting to allow people to come back into the office, I'm curious about some reflections on what people figured out about fully remote work or hybrid work, whether it's in the structure of these pairs or in general for Menlo. What do you think some of the greatest adaptations have been?

The first is the part that everybody's curious about who knows us well. They're like, “How did you make the remote pairing thing work?” Honestly, that was the easiest thing. You and I are remote pairing in a conversation and creating a show right now. You easily come to Menlo and set up your microphone and computer. We could have been together and all that sort of thing, but we're doing it remotely. It's not hard to imagine.

If we're programming together, we're going to have a second screen, a code we're co-developing that we're discussing. In some ways, pair programming remotely might be slightly easier because, for one simple physical reason, you and I can look at each other. When we're pairing shoulder-to-shoulder, if I want to look at you, I have to turn my body and look at you, and then look back at the screen. In this case, I have to dart my eyes back and forth between the code and the screen. That part was easy. We had been doing remote pairing for clients for a decade prior to now.

The harder part, this is the part that still worries me and I think we're paying a little bit of a work-from-home tax. This is the serendipity that happens when the payors are sitting close to one another and they're overhearing and supporting each other. We just saw that where there was one pair that was working on something, another pair had solved it, and they didn't know it. The simple way I describe it is it's working. It is not ideal.

You wrote about this in the blog post, adaptations to the standup meeting to make that an effective virtual standup virtual tour. One thing you wrote about that was interesting was, in the spirit of, “Let's figure it out, let's experiment.” It was your recognition that the virtual fifteen-minute standup wasn't enough time. You added some lunch sessions and some other time that wasn't happening in the physical workplace. Can you share a little bit about that?

It was the team leading that effort. One of the things is a challenge in the pandemic that isn't as much of a challenge for us as it is in most organizations is loneliness and isolation. Because we're all paired together and we're switching the pairs at least every five days, you still have a social connection with the people at work. We are apart physically to be safe and healthy. We are not apart socially. We thought the idea of social distancing was an incorrect term, at least in our context. Physical distancing was important. Social distancing is not required.

By pairing people together, the loneliness and isolation caused by the pandemic will not be much of a challenge anymore. Share on XHowever, one of the things the team noticed early on was, they don't see Rich and James anymore. They're used to us being out in the room and saying good morning to them, and “How'd that sales conversation go that I saw you in yesterday?” They weren't seeing that. “How are you guys doing? How are you feeling about things? How are revenue and all that stuff?” The team said, “Could we get together with you?” We established this pattern of what we call Thursday Lunch with Rich and James. We started this three weeks into the pandemic and it is now a staple. Every Thursday, they have lunch with Rich and James.

If James isn't going to be there, I will. Sometimes we're both not there, so now we call it Thursday with or without Rich and James, but the fact of the matter is, it was this regular connecting point. When people are in the building, some of them would gather in the room with the Owl camera. The people who are at home because we're obviously not 100% remote anymore. That has been a good addition to our culture.

Topics we talk about are timely topics. Topics of interest in that moment. Early on in the pandemic, a lot of discussions about financials because we took a big financial hit early on in the pandemic. Right now because we're moving to a new building soon, they're curious about the new space, how's the lease negotiation going, and all that stuff.

I have a final question on that before we wrap up. You said in the one blog post that pre-pandemic, you might have expected to need to move to a bigger space. Are you indeed? You said, “Maybe we need a smaller space.” Is that how it's playing out?

It is. In our vision, we anticipated the next move would be three times the physical size of our current space, which would've been huge. Right now, if we go ahead with the lease we're negotiating, it'll be slightly smaller than the space we have. It'll still be a big open room. You've been here. This is in the sunlight-less basement of a parking structure in Downtown Ann Arbor. This is going to have lots of windows, an amazing amount of glass, and the ability to look out on nature, and see sunlight. I know the team is excited about moving up to the ground level.

The Menlo Way is not predicated on being in a windowless basement space. That's good to know.

No. I would say we proved that the Menlo Way could survive being ten years in a windowless basement parking structure. Now we're done proving that point. We'll go prove some other points next.

Rich, thank you for sharing your stories of adaptation and figuring things out based on the culture that you've built there at Menlo. I look forward to someday being back in Ann Arbor and come see the new space. In the meantime, I'm excited. I'll see you in Traverse City at The Michigan Lean Consortium Annual Conference. Again, that's August 10 and 11, 2022 in Traverse City, Michigan. MichiganLean.org is where you can learn more about that. In the meantime, please check out Rich's books, Joy, Inc. and Chief Joy Officer. If you come to the MLC Conference, you can ask Rich your own questions. I hope I've asked decent questions here. I do appreciate your answers and the conversation.

It's always fun talking with you, Mark. For your audience who either haven't been to Michigan or haven't been to that part of Michigan, there could be no more beautiful spot in the United States than Traverse City in August. Just that alone should be worth the price of admission to getting to the conference. Obviously, if people come, we'll have some great conversations with them.

The Michigan Lean Consortium is running the event, but it's not limited to those with a Michigan driver's license. I hope some people will come traveling for this. If you live in Michigan, the Michigan Lean Consortium has all kinds of great opportunities and ways to learn and network throughout the year. Again, check them out. MichiganLean.org. Our guest has been Rich Sheridan, CEO of Menlo Innovations. Thank you so much for being here, Rich.

Important Links

- Menlo Innovations

- Episode 189 – Previous Episode

- Joy, Inc.: How We Built a Workplace People Love

- Chief Joy Officer: How Great Leaders Elevate Human Energy and Eliminate Fear

- The Michigan Lean Consortium Annual Conference

- Lead With Joy and Watch Your Team Fly

- Extreme Programming Explained

- The Savvy Leader's Guide to Employee Engagement

- KaiNexus.com/Engage

- Stiles Associates

- https://MenloInnovations.com/stories/culture/Coping-With-Our-Own-Swiss-Family-Robinson-Ordeal-Part-1

Please scroll down (or click) to post a comment. Connect with me on LinkedIn.

Let’s work together to build a culture of continuous improvement and psychological safety. If you're a leader looking to create lasting change—not just projects—I help organizations:

- Engage people at all levels in sustainable improvement

- Shift from fear of mistakes to learning from them

- Apply Lean thinking in practical, people-centered ways

Interested in coaching or a keynote talk? Let’s start a conversation.

![When Was the Last Time a Leader Around You Admitted They Were Wrong? [Poll]](https://www.leanblog.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/Lean-Blog-Post-Cover-Image-2025-07-01T212509.843-238x178.jpg)

![When Was the Last Time a Leader Around You Admitted They Were Wrong? [Poll]](https://www.leanblog.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/Lean-Blog-Post-Cover-Image-2025-07-01T212509.843-100x75.jpg)