If you don't care about sports or statistical process analysis, this isn't the post for you… but it was interesting for me to try to wrap my head around the data behind a headline that I'll write about here.

Previous Discussion About This

Back in 2011, right after the end of the NFL regular season, I wrote a blog post about how contractual individual player incentives, paying them bonuses for individual statistics, could distort the game:

Individual NFL Player Incentives – Why Are They Necessary? Do They Distort the Game?

This Week's Headline

Now that the NBA regular season has just ended (Go Spurs, Go!), I heard about this story featuring Maurice Harkless of the Portland Trail Blazers, as they move into the first round of the playoffs:

“Blazers player secures $500,000 bonus by not taking 3-pointer in final game of the season“

How did he get a bonus for NOT shooting the ball? Many basketball players LOVE to shoot and score. A player's individual “points per game” average has traditionally been one measure of how great a player is, which affects their ability to negotiate future contracts and pay. Of course, some of that is changing in the NBA thanks to the “analytics” movement that spread from baseball (see my posts on “Moneyball“) and has been led by a fellow MIT alum, Daryl Morey in Houston.

There's a natural intrinsic motivation for a player to shoot the ball, especially so to make the shot… scoring points, of course, means a better chance to win the game.

Let's look at some data (yes, we can do that in the Lean methodology)…

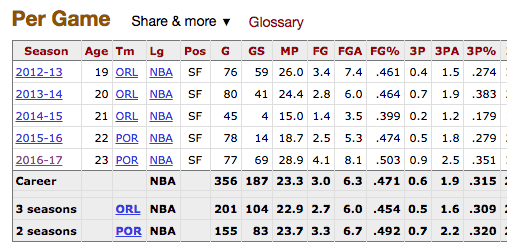

In this past season, Harkless took an average of 2.5 three-point shots per game. For his five-year career as a whole, he's averaged 1.9 of those per game.

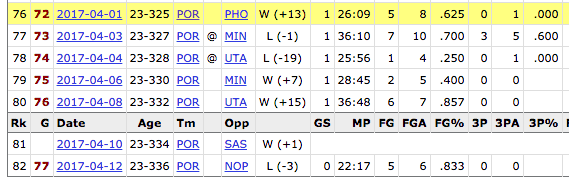

Why did he only take ONE shot in his last four games of the season, as shown in the game log?

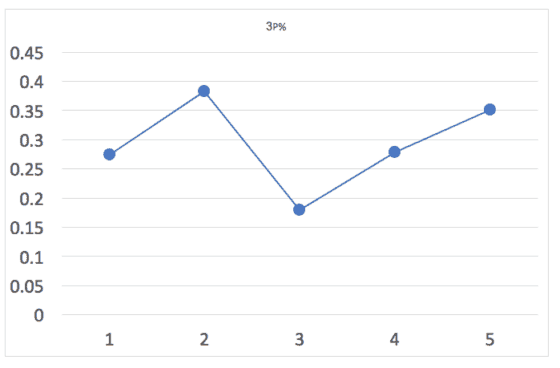

See how his end-of-season three point percentage (3P% in the first table) was .351?

That meant he made 35.1% of his three-point shots for the season.

As reported, he had an INCENTIVE CLAUSE.

“As pointed out by The Vertical's Bobby Marks, Harkless could earn a $500,000 bonus by shooting 35% or above from three-point range for the season.”

Half a million dollars! His annual salary for the season was just under $9 million, so $500,000 is meaningful.

At the end of game number 77, when he made 3 of 5 of those shots in the game, his percentage sat at .3523 for the season (68 out of 193).

His next game, where he went 0 for 1 from behind the arc, brought the percentage down to .3505 for the season, just above the threshold for the bonus.

SCARY! If he knew about the stats and how close he was.

The allegation is that Harkless avoided three-point shots in the last few games:

“So, rather than risk that bonus, Harkless did the smart thing — avoid taking a three-pointer.”

We don't know that for a fact, but Harkless tweeted about it after the end of the season, indicating that he at least knew about the incentive after the fact:

https://twitter.com/moe_harkless/status/852406143041257472

I'm not blaming Harkless for being selfish or doing the wrong thing. You get what you incentivize, right? It's not a huge scandal or anything, just an interesting scenario.

Possible shooting performances in those past four games that would have affected his bonus:

| Shots Made | Shots Attempted | Final % | Bonus / No Bonus |

| 0 | 1 | .3487 | No Bonus |

| 1 | 2 | .352 | Bonus |

| 1 | 3 | .3503 | Bonus |

| 1 | 4 | .3485 | No Bonus |

| 2 | 5 | .3518 | Bonus |

| 2 | 6 | .3500 | Bonus |

So if he had gone “0 for anything,” he'd lose the bonus for being below .350.

A funny scenario would have been going 2 for 6, which would have left the numbers at exactly 70 shots made out of 200 on the season, or exactly .350.

Would .350 on the nose have gotten the bonus? Wow, that would really depend on the contract language. It supposedly said “35% or above” in the contract, so I guess so.

Portland had already clinched a playoff spot, so the last few games were pretty meaningless.

There might have been a situation where he or another player would be pressured into trying to score a lot of points to hit an incentive threshold.

Or, had he taken one and missed, he would have had a great incentive to put up another shot… since making it would get him back above the threshold. That could have become a situation where, as in blackjack, you might be “throwing good money after bad.” Had he missed four, he'd have to make two in a row to get back about .350.

We could have seen a situation where Harkless would have been launching tons of threes in the last game to try to earn a bonus.

Or, the team could have sat him to avoid getting (or avoid losing) the bonus.

Why Do You Need Incentives?

It's interesting to think about WHY an incentive like this would be needed to extrinsically motivate a player. I'm not a salary cap expert, but maybe incentives count differently against the cap?

From this page:

74. Can incentives be built into a contract? How do they apply to team salary?

“Performance incentives are classified as either “likely to be achieved” or “not likely to be achieved,” with only the likely incentives included in the player's salary and team salary amounts.”

“Incentives must be structured so that they provide an incentive for positive achievement by the player or team, and are based upon numerical benchmarks (such as points per game or team wins) or generally recognized league honors1. The numerical benchmarks must be specific — for example, a bonus may be based on the player's free throw percentage exceeding 80%, but may not be based on a relative measure such as the player's free throw percentage improving over his previous season's percentage. Certain kinds of incentives are not allowed, such as those based on the player being on the team's roster on a specific date or for a specific number of games.”

Man, this gets complicated. Harkless, before this season, was a career .300 shooter.

Was hitting .350 “not likely to be achieved?” I bet the team categorized it as such, to not hit their salary cap?

Here's a run chart of his three-point percentages for his five seasons, including this year:

In his second season, he shot almost 40%… so I guess he showed it was possible?

Is Harkless improving or is he part of a “stable system” with stable performance? Will his shooting percentage regress to the mean next year? Stay the same? Get better? We don't know from the data. Your hypothesis is as good as mine, especially if you're watched him play.

As Business Insider said

“[likely] had a bonus attached to his three-point percentage, as incentive to improve.“

Incentive to improve??? He already had a lot of incentive to improve, including:

- Helping his team win

- Keeping his job

- Increasing his future salary

- Being a good teammate

- Not wanting to embarrassed by missing shots

Do the Data Suggest Harkless Was Intentionally Altering the Way He Played?

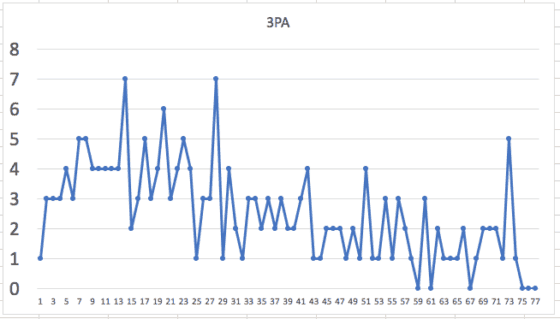

To answer the question of “was his performance unusual in the last games?” or “was that special cause?”, I did a run chart of his three-point shots per game this season — it's great that you can download this data into a spreadsheet. Games where he didn't play are not included.

The most shots Harkless took in a game was 7. Until it got late in the season, he never played a game without taking a least one three. It looks like there was a bit of a downward trend over the season, but I warn against using linear trend lines for workplace data.

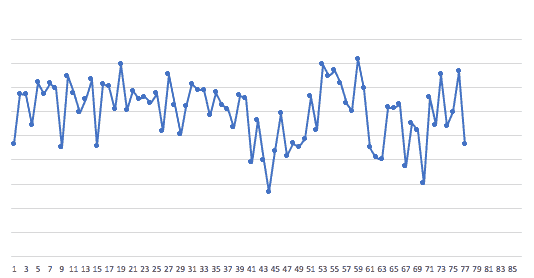

Minutes per game was pretty stable throughout the season, an average of 28.9 per game. Here's a run chart visualization of that:

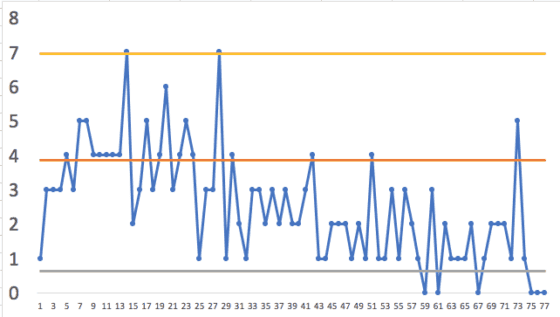

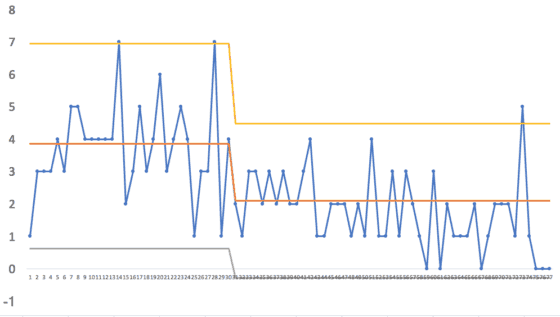

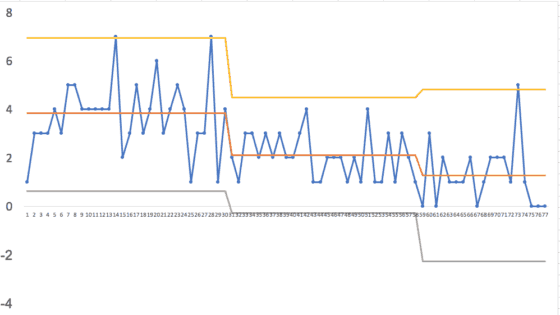

If I draw a control chart (or “process behavior chart” using the first 20 games as the baseline numbers, we get this chart for three points attempted per game (3PA):

If this type of chart is new to you, see my tutorial on how to make them or my webinar on managing performance data (it's part of a workshop I'm doing on “Better Metrics“).

The original lower and upper “natural process limits” (as Don Wheeler calls them) are 0.63 and 6.95, so the games where he took 7 shots are perhaps “special cause,” mean it's unlikely to just be chance or noise in the data. I don't know what was different about those games when he took 7 shots. That was unusually high.

Any game with zero attempts would have indicated a special cause, such as playing less than normal in the game.

As the season went on, we see many stretches of eight consecutive points below the old average, which indicates the system had changed… that run of 8 points below the average is also a “special cause” indicator (see the “Western Electric Rules“) because it's unlikely to be due to chance. Something changed.

With shifted limits, indicating the new system, the lower and upper limits become -0.28 (or zero, in effect) and 4.48, with an average of 2.1 shots per game.

Toward the end of the season, the one game where he took 5 three-points was above the natural process limit.

There's a stretch of what looks like 12 games below the new mean, which indicates another process shift.

So it looks like the Harkless season was three different systems, as shown below:

Toward the end of the season, there's the one positive outlier game. But, we can't conclude that his last four games of 1 shot, then zero, zero, zero is anything more than “noise in the system.”

What Do I Conclude?

It's possible that Harkless was intentionally not taking threes because of the bonus… but the data doesn't indicate that it's necessarily true. You'd have to ask him.

It could be just randomness or how the games went.

He might have been gunning for .350 (by not firing way) or he didn't notice until after the season.

In the workplace, process behavior charts can help us test a hypothesis about things being stable or something changing.

I did similar analysis in 2012 after American Airlines pilots were accused of staging a “sickout.” The data showed that the number of illnesses was likely chance or randomness (or “common cause” variation).

Can SPC Show if American Airlines Pilots are Staging a “Sick Out”?

Have you used charts like this to prove or disprove a workplace performance hypothesis?

Please scroll down (or click) to post a comment. Connect with me on LinkedIn.

Let’s work together to build a culture of continuous improvement and psychological safety. If you're a leader looking to create lasting change—not just projects—I help organizations:

- Engage people at all levels in sustainable improvement

- Shift from fear of mistakes to learning from them

- Apply Lean thinking in practical, people-centered ways

Interested in coaching or a keynote talk? Let’s start a conversation.

![When Was the Last Time a Leader Around You Admitted They Were Wrong? [Poll]](https://www.leanblog.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/Lean-Blog-Post-Cover-Image-2025-07-01T212509.843-100x75.jpg)

Some comments from when I originally posted this news story on LinkedIn:

Vince Capasso, MSF, FACHE, Master Black Belt

Great example of the dangers of one dimensional metrics

Rick Foreman

Interesting based upon the somewhat uncontrolled metrics of being voted to at least the 3rd Team All NBA, which will net Paul George another $75mm.

S. Max Brown

Thank you for sharing this, Mark! Great example of the power of systems — for better and for worse.

Michael Bremer

Good example of ‘metrics’ sometimes driving crazy and sometimes driving harmless behaviors. You can’t over read too much into this. If the team had needed someone to take a risk in order to score points to win a close game in order to make the playoffs….he may have behaved differently. Still I like the example. It was simply smart play given the team’s playoff position and his incentive pay metrics.

Ken Robinette

I have seen this phenomenon play out so many times in the business world. What gets measured gets focused on, effective leaders understand intended and un intended outcomes, that is why balance score carding is so powerful and so difficult at the same time.

Samuel Selay

Great practicle example of performing to a set metric at all cost because that’s how Harkless was measured/rewarded.

Here is the news story that Rick Foreman was referring to:

NBA awards votes could mean an extra $75 million for Pacers’ Paul George

Hi Mark,

A few points I think you left out in your analysis.

1) Did the incentive help Portland make the playoffs? They were a bubble team, so a single win was the difference (depending on the tiebreaker). It is conceivable that the .070 jump in his percentage helped his team win at least one game they would otherwise have lost.

His jump was somewhere in the neighborhood of a hundred extra points on threes for the year.

2) More importantly, did the incentive change the way he prepared for games? Did he practice more? Did he figure out how to practice more effectively? Did he seek out information/coaching to improve his shooting style?

3) Finally, next year, will he regress without an incentive, or will the gains he made be lasting?

I am not a fan of incentives that require a person to just ‘do better’. But if the incentives is well designed, and creates an underlying, lasting improvement, then there is value.

Loved the article,

Jeff Hajek

Great questions, Jeff. Thanks for commenting.

1) Hard to answer. I guess one challenge (fallacy?) in organizational goals is that somebody is smart enough to know how individual incentives add up to team success.

100 extra points on a higher percentage means he was more “efficient” as a scorer (yeah, they use that term now in basketball).

How would a “strategy deployment” process work for an NBA team? Is “true north” winning a championship or being a profitable franchise? That’s up to the owner, I guess.

What, then, are goals and measures for the General Manager? For the Head Coach? For the Assistant Coaches? For each player?

This quickly gets complicated, right? What if there are conflicting individual incentives for players? Does that interfere with teamwork and winning?

I wonder if an NBA team has experimented with focusing LESS on individual incentives to more team-based incentives?

More in a bit…

2) Great questions. I don’t know the answer. I guess my question is shouldn’t Harkless have been doing those same things, as a professional, with or without the .350 goal and $500,000 incentive?

3) Only time will tell! :-)

I think the challenge with incentives is “well designed.” Dan Pink, in his book Drive, talks about how incentives work, but they have side effects. Can we design the least-dysfunctional metrics?

A goal of “8 is great” (8 accounts per customer) was really dysfunctional at Wells Fargo.

A goal of 14 days waiting time for appointments at the VA got really dysfunctional.

When it’s easier to “distort the system” or “distort the numbers” than it is to actually improve system… that’s where we get into trouble.

My point on #2 is about prioritization. There is only so much time to practice (or in our world, to make improvements). Incentives tell you what is important to the decision makers. I doubt Harkless was actively thinking he didn’t want to work on his 3’s, but there are only so may hours in a day.

The key is whether the incentives are done well, in the same way that there is Lean and L.A.M.E.

Good point.

More from LinkedIn:

Tammo Heeren, PhD

“Incentives drive behavior”. Why not simply shoot enough 3 pointers from the start of the season to just get above the 35.1% level (maybe one is good enough) and then stop trying? These type of silly things get organization in trouble.

My response:

Yes 1 for 1 on the season would have earned a bonus. Might have also gotten him released from the team if he stopped shooting from 3 after making that first shot.

:-)

As pointed out on LinkedIn, Harkless shot only 2 for 11 from 3 in the first two playoff games.

Maybe the incentive should have included playoff games?

Another thing to check would be his performance in previous years. What did his “3p system ” look like over the course of a year before the incentive was in his contract?

One chart in the post shows previous years’ performance.