I'm still reflecting on what a great conference the Society for Health Systems put on again this year. Here are some highlights from other talks… (see also my previous two posts)… if you're curious about “Shocking Doctors” in the post headline, be sure to read to the end of the post.

Airica Steed, now with the University of Illinois, gave a presentation about improvement work in a previous role at Advocate Health. They used Lean, as part of their Baldrige journey, to improve key measures over just a few years, including:

Airica Steed, now with the University of Illinois, gave a presentation about improvement work in a previous role at Advocate Health. They used Lean, as part of their Baldrige journey, to improve key measures over just a few years, including:

- Outpatient patient satisfaction increased from the 40th percentile to 93rd percentile

- Workforce engagement scores went from the 25th percentile to the 99th percentile

- They went from a $50 million deficit and losing money for 10 years to making a $10 million profit

Those are amazing results.. and it was done through patient-centered operational excellence methods.

I also saw a fun presentation by my friend Mike Stoecklein, from the ThedaCare Center for Healthcare Value, my guest for podcast episode #156, talking about his interactions with W. Edwards Deming.

I also saw a fun presentation by my friend Mike Stoecklein, from the ThedaCare Center for Healthcare Value, my guest for podcast episode #156, talking about his interactions with W. Edwards Deming.

Mike shared a lot of lessons from Dr. Deming, including the idea that “People go to other companies and other countries and try to copy, but they don't know what to copy.” As Doris Quinn discussed, you can't copy what you've seen when you have a weak foundation – hampered by the “prevailing style of management,” which includes:

- Short-term focus

- Results by any method

- Dividing the organization into parts and then managing the parts, instead of the system

- Managing from the office and the conference rooms

- Competition, win-lose, focus on individual

He talked about Deming's red bead experiment, the need to better understand variation (including mentions of the great Wheeler book Understanding Variation: The Key to Managing Chaos), and other topics.

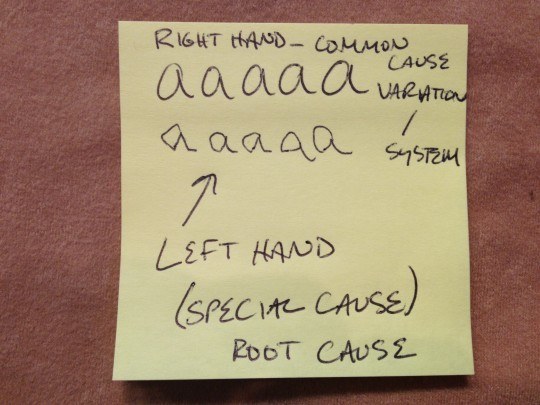

He did a nice exercise for the audience that illustrated “special cause” versus “common cause” variation.

When I wrote five consecutive a's with my dominant hand (my right), the variation is “common cause.” I could reduce variation by having a better pen, a smoother writing surface, slowing down, etc.

Switching to my left hand… that's a “special cause” and you can see the increase in the variation. I could fix that variation by removing the special cause – by going back to my right hand.

Leaders and managers waste a lot of time looking for special causes when none exist – we over-react to special cause variation (the theme of my webinar on Statistical Process Control or SPC).

Oh, and you HAVE to read his blog post from yesterday about a lunch table discussion he was a part of at the conference: B.F. Skinner Would Be Proud.

Why did an attendee SERIOUSLY think that giving doctors electric shocks might be a good way to trigger the right behaviors?? Read Mike's post. Read it!! It's a real shame how some people are so quick to blame the individual instead of the system.

What do you think? Please scroll down (or click) to post a comment. Or please share the post with your thoughts on LinkedIn – and follow me or connect with me there.

Did you like this post? Make sure you don't miss a post or podcast — Subscribe to get notified about posts via email daily or weekly.

Check out my latest book, The Mistakes That Make Us: Cultivating a Culture of Learning and Innovation:

Thanks for sharing this Mark. These are the conclusions I came away with after my SHS presentation:

Here’s what I learned:

1) most of those in attendance had heard about variation, some about the two types (common & special cause) and most learned it in a statistics class in college (except for the music and english majors – I would place the business and healthcare managers in this group who never got the word)

2) “understanding variation” seems to have been placed into a container called statistics and the analytic (process) category is not seen as distinct from enumerative. (There is an important distinction and Dr. Deming and Dr. Don Wheeler do a nice job explaining this). It is generally seen as a “technician” thing – often placed in the “six sigma” box (“those people” who make the control charts).

3) most in today’s workshop were not aware of the application of understanding variation in the application of people (the most important area). This includes the connection with “appreciation for a system”. When we see any outcome (or behavior) our first question should be “what is the system that could be causing that?”, and not focus immediately on the individual.

4) if people didn’t learn about variation in college, it’s not likely to be learned on the job. It does not seem to be part of what is taught by the “lean people” (they either don’t think it’s important or don’t understand). I have yet to hear anyone ask, “I wonder if that was due to common cause variation or is it a special cause?”

5) In the lean curriculum, people learn about “waste” (muda) but they don’t understand that management’s lack of understanding of variation (and systems thinking, and psychology and theory of knowledge) leads to the production of mura (unevenness), muri (overburden) and muda (waste). There does not seem to be an awareness that it’s another example of “burnt toast management”. Instead of working up-stream to eliminate the causes of muri, mura and muda (top management) they seem to be content to have middle management and associates identify (and try to eliminate) the 8 types of waste down stream (scrape the burnt toast).

6) most senior management does not understand variation or why it’s important to learn it. They are not aware that most of what they do every day is “tampering” and the notion of applying the concepts of “systems thinking” and “understanding variation” to the management of people is not even under consideration. This includes the love affair with performance evaluation, performance management and pay for performance systems. These are all based on the “mythology of the prevailing style of management” (Deming’s term).

7) there may be a few rare individuals who saw or heard Dr. Deming when he was alive, have read his books and (in other words) “get it”. The majority appear to not have a clue about this knowledge. Their deficit of knowledge in this area is not even a suspicion.

8) If Dr. Deming were still alive (he’d be 113 years old) the story may be different, but the idea of understanding variation and the consequences of not understanding has been largely lost to the world in 1993 (the year he died)

9) it’s up to us to bring this to the attention of others.

Personally and professionally, I feel very fortunate that I was exposed to Dr. Deming’s work and “Out of the Crisis” before I really learned about Lean or TPS. My dad attending a Deming 4-day seminar when I was in high school and I heard all about him.

Maybe I’m a rare breed, but I have run the red-bead experiment for Lean clients and I have coach managers on how to create and interpret control charts to avoid overreacting to every up and down in the data…

But this understanding and practice is far too rare.

I cringe when Lean people want to use slogans and posters or rewards and incentives to bribe or force people to participate in 5S, kaizen, what have you… and I cringe when I see people forcing tools on people without having an appreciation for psychology, systems thinking, or the role that senior managers play in determining a system and culture.

I’m not indicting the whole Lean community by any means and I’m certainly not perfect… but we should be striving to introduce more people to the work and lessons of Deming, Wheeler, Joiner, Scholtes, Senge, etc. and not just Ohno and Shingo.

Mike – I like your description above about the importance of variation and how understanding it is critical to understanding a process. You are right that in “lean” circles, you don’t often hear a discussion of common vs. special cause variation. You also don’t often hear “standard work” being framed as a tool to eliminate special cause variation and enable focused improvement (or elimination) of the common inputs to the process. I see too many people off and running with an average in hand having no idea what the process is truly delivering.

Thanks for your comment, Dan. I don’t recall seeing you comment before. I hope you will be back and that you’ll keep commenting and participating on this and other posts…

I agree wholeheartedly with the observations being shared. For over 20 years, I have been doing this TQM, Six Sigma, Lean, Performance Improvement, and/or Operational Excellence stuff. In every organization with whom I have worked/consulted, the key challenge is to get people to use the data they already have and to understand it properly. Then, they have to quit making lists and DO SOMETHING! When teaching basic Lean/6 Sigma/Improvement concepts I have used the article “UNDERSTANDING VARIATION” by Tom Nolan and Lloyd Provost in QUALITY PROGRESS magazine as a pre-read or follow up resource. Especially within healthcare (my current field), there are SO many “urban myths” used to justify not doing something or to justify a really dumb practice continuing. People look at run charts and chase the “dots.” Up is good – celebrate. Down is bad – chastise. Dr. Deming was right (and I actually had a chance to see his seminar!) – “If I had to reduce my message for management to just a few words, I’d say it all had to do with reducing variation.”

Also, Donald Wheeler’s book, UNDERSTANDING VARIATION should be a must read in all management and leadership courses – IMHO!

I agree on Wheeler’s book.

Here is a recording of my webinar on variation, SPC, and management thinking:

https://www.leanblog.org/spc-webinar-archive/

As I try to describe on this slide, we can’t just do D’oh and Woo-Hoo for every single up and down within common cause variation: