Recently, I saw someone reference a chapter from Dr. W. Edwards Deming's book Out of the Crisis on LinkedIn–Chapter 11, titled “Common Causes and Special Causes of Improvement. Stable System.” It was a good nudge for me to revisit a section I hadn't read in a while. I'm glad I did.

It's a short chapter, but it's packed with insight–and it feels just as relevant (if not more so) than when Dr. Deming wrote it in the early 1980s. Maybe even more so now, when so many organizations are awash in data but still react more than they respond.

As I re-read the chapter, I found myself reflecting not only on Deming's points, but also on the foundational role of Walter Shewhart–who made his key observation about variation and systems just over 100 years ago, in 1924. And that's worth commemorating.

Two Types of Mistakes We Still See Today

Deming described two common mistakes that stem from misunderstanding variation:

Mistake No. 1: Ascribing a problem or variation to a special cause when it's actually part of the system (a common cause).

This leads to tampering or overreaction. We tweak processes unnecessarily, blame people unfairly, or jump to conclusions without understanding the system.

Mistake No. 2: Attributing a variation to the system when it's actually a one-off special cause.

This leads to inaction. We miss important signals and fail to address root causes that could have been corrected.

Neither mistake is intentional. But both can be costly–and often demoralizing to those doing the work.

The Supervisor Trap

Deming points out that many supervisors commit Mistake No. 1 when they blame a worker for a defect or delay, without first understanding the system behind the outcome.

That made me think of conversations I've had in healthcare settings, where a nurse gets blamed for a late discharge, even though:

- The patient transporters team was short-staffed (possibly due to cost cutting)

- The physician was late entering orders (likely due to systemic issues)

- The system simply wasn't designed for reliability

We know better, yet these stories still happen all the time. Because the pressure is real. The dashboard is red. The email from leadership is already sent. Someone has to be held accountable–right?

Not if we want to build a culture of improvement.

What Shewhart Gave Us–Then and Now

Walter Shewhart's contribution wasn't just a control chart (or what Don Wheeler calls “Process Behavior Charts”)–it was a way to make better decisions in the face of uncertainty. His plus/minus 3-sigma limits weren't about chasing precision–they were about minimizing the net economic loss from both types of mistakes.

Deming echoes this point: you can avoid Mistake No. 1 all the time, or Mistake No. 2 all the time–but not both. Trying to do so is a fantasy. The key is to balance the risks using a rational method.

That's what a Process Behavior Chart gives us today, as I wrote about in Measures of Success. A visual, statistical way to answer:

“Is this data point a signal worth reacting to–or just noise to be better understood?”

It's a powerful tool. And one I wish more leaders had in their daily management practice.

Lessons for Modern Leaders

A few reminders I took away from re-reading this chapter:

- Stability matters. Don't improve a system you haven't first stabilized.

- Act differently based on the type of cause. Improving the system (common cause) requires different action than investigating a special cause.

- Psychological safety is essential. If people are punished for common-cause variation, they'll stop speaking up altogether.

- Avoid the illusion of control. Just because a dashboard turns red doesn't mean a person failed. Start with the system.

- Teach this thinking. Deming's and Shewhart's ideas aren't commonly taught–but they can be learned, and they can be shared.

Act Differently Based on the Type of Cause

One of the most practical–and overlooked–insights from Shewhart and Deming is that different types of variation require fundamentally different types of action. So let's dig into that.

It sounds simple. But it's not always intuitive. And it's even harder to practice consistently under pressure.

Let's break it down:

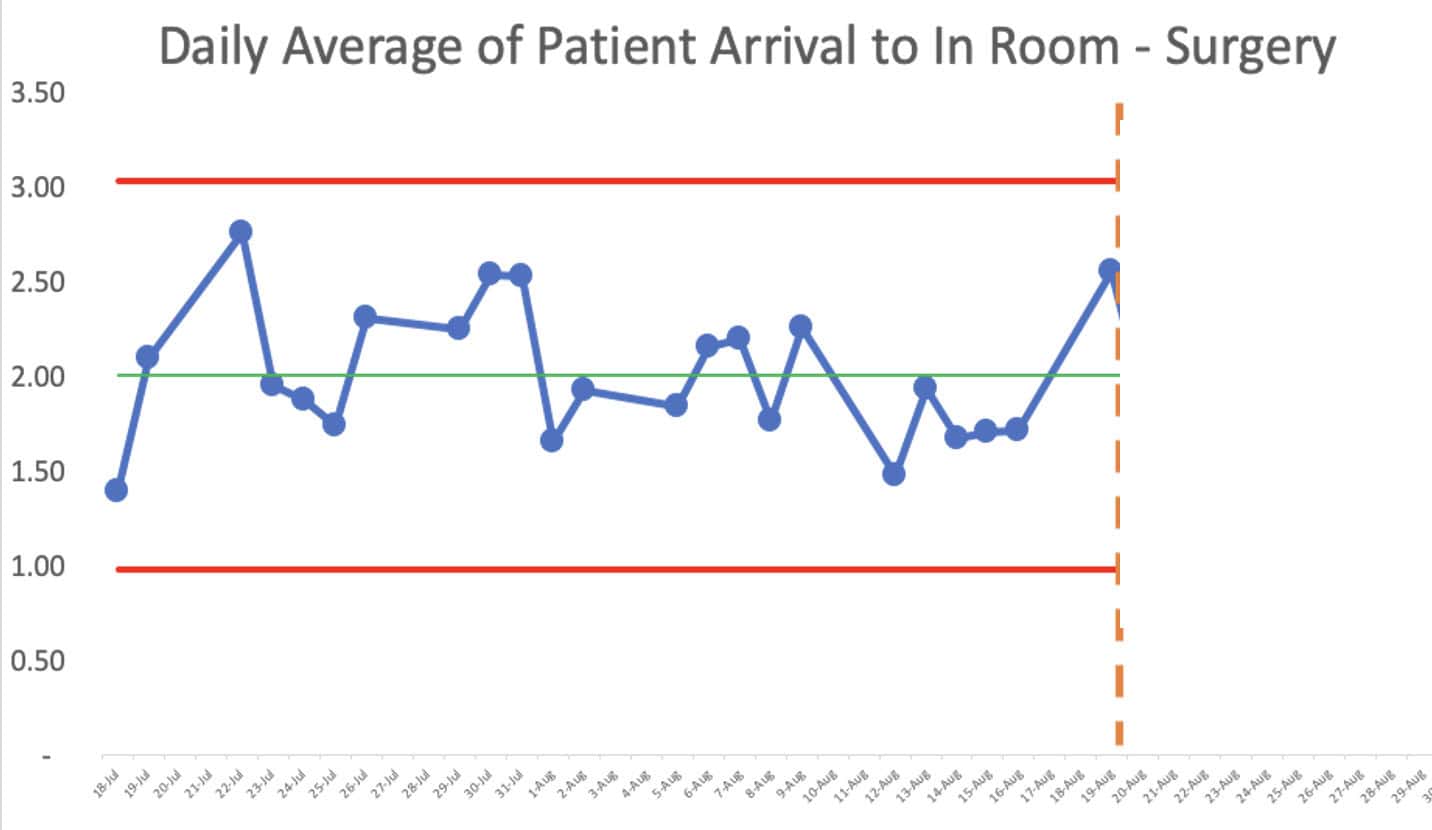

Common Cause Variation: Improve the System

Common cause variation is built into the current design of the system–it's the predictable, random “noise” we get when a process is stable but not perfect. If your process is producing late discharges or defects every day, and the data fluctuates within a consistent range, that's common cause variation.

It would look like this in a PBC:

The right response? Improve the system.

- Redesign workflows

- Standardize practices

- Eliminate waste and bottlenecks

- Invest in training, tools, and better design

Don't single out a person or one moment in time. Or a single data point. That's tampering–and it can make things worse.

As Deming said,

“No number of exhortations, incentives, or threats will improve the output of a stable system.”

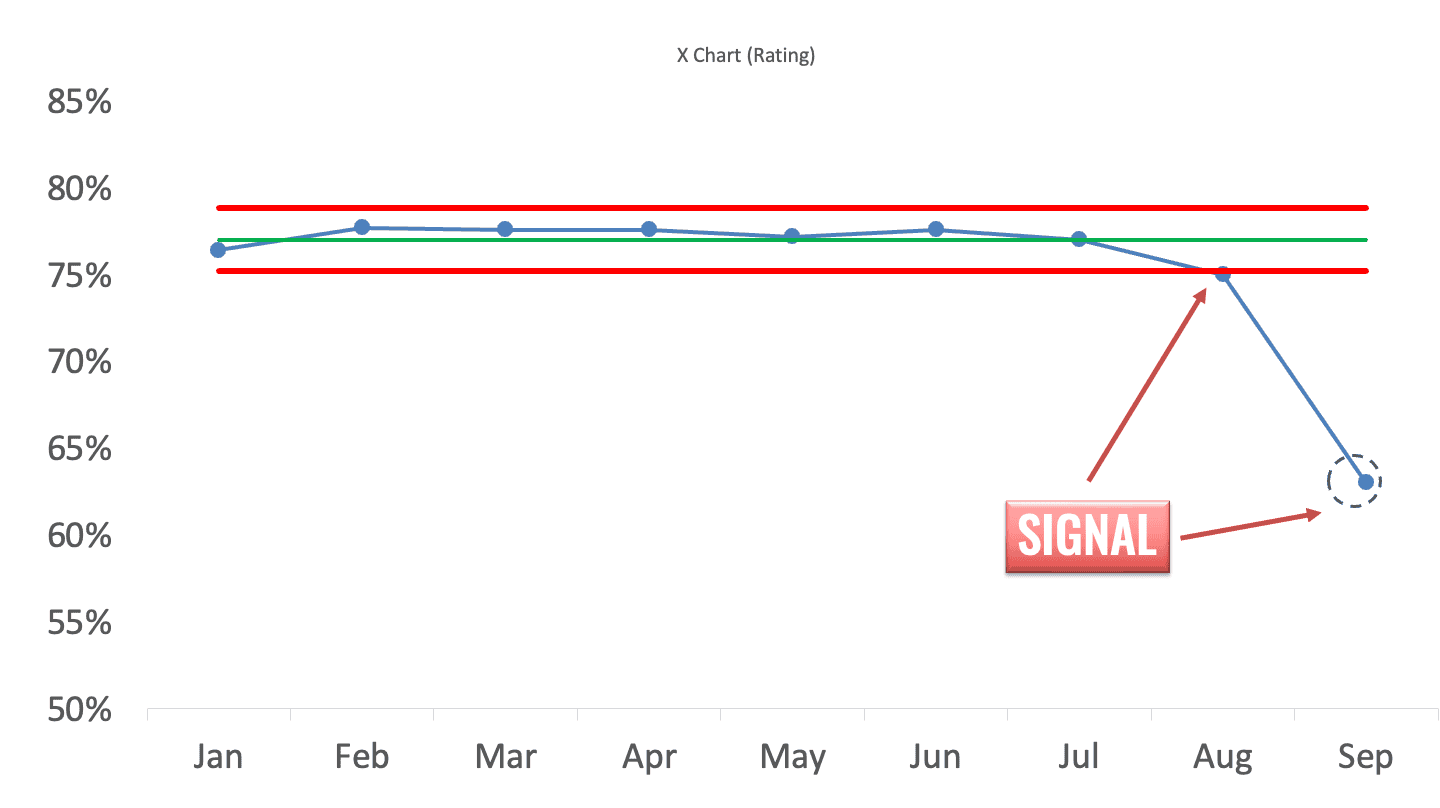

Special Cause Variation: Investigate the Exception

Special cause variation is something unusual, unexpected, or outside the norm. It might be a data point that falls outside the control limits on a chart–or a shift in the pattern that signals something has changed.

Maybe:

- A nurse reports a one-time delay due to a broken elevator.

- A lab test turnaround time suddenly doubles after a software update.

- A new employee's error rate is significantly different from the group average.

A special cause looks like this:

The right response? Investigate the cause.

- Ask what's different about that situation or moment.

- Look for changes in people, methods, materials, or equipment.

- Fix the root cause or adjust the process as needed.

This is detective work, not process redesign. Don't overcorrect your whole system based on a one-off blip.

Why the Distinction Matters

If we treat common cause like special cause, we waste time, demoralize people, and inject instability.

If we treat special cause like common cause, we miss opportunities to solve real problems.

Here's a quick analogy I use in workshops:

If a car drifts slightly within a lane on the highway, that's common cause. You keep your hands on the wheel, but you don't jerk it back and forth. If a tire suddenly blows out–that's a special cause. Pull over. Investigate. Replace the tire. Then drive on.

Different cause, different action.

That's the heart of good management. That's how we lead better, not just react faster.

Final Reflection

100 years later, Shewhart's work still helps us lead with more clarity and less chaos. Deming helped translate it for management. Now it's up to us to apply it–and to teach it–especially in environments where the pressure to react is constant.

Let's not just manage variation–let's understand it.

And let's build systems where people are set up to succeed, not blamed for outcomes they couldn't control.

Please scroll down (or click) to post a comment. Connect with me on LinkedIn.

If you’re working to build a culture where people feel safe to speak up, solve problems, and improve every day, I’d be glad to help. Let’s talk about how to strengthen Psychological Safety and Continuous Improvement in your organization.