Updated: See my 2nd comment about how I managed to get a pair glasses from a kind neighbor. I'll also post a few photos at the bottom of the post.

Monday is the so-called “Great American Eclipse,” a total solar eclipse that has a totality path that crosses just the United States. Readers in Canada and Mexico can see the partial eclipse. I will be in Orlando, where we get an 85% eclipse at about 2:51 EDT. A total eclipse is a pretty rare event on any particular spot on earth, being seen, on average, once every 375 years. The next total eclipse to cross the U.S. will be in 2024.

Hear Mark read the post (subscribe to Lean Blog Audio):

Any rare event creates a number of challenges when it comes to manufacturing and supply chains. We're seeing a pretty historic “spike” in demand for products like the inexpensive glasses that allow one to safety view the eclipse (our friends in the totality zone can look at the totally-eclipsed sun safely, but that's the only time).

You could call it “supply chain challenges” or a “lack of planning on my part,” but I cannot find eclipse glasses anywhere. There are MANY articles online about this widespread problem.

As I typed those quote marks above, it made me think of that one old Chris Farley character (Bennett Brauer) from SNL and his air quote fingers at the Weekend Update desk.

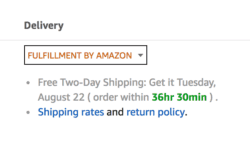

I'm not the only one who is finding it difficult to find eclipse glasses at a store. It's too late to order them on Amazon and they were out of stock in the middle of last week – a timeframe in which Amazon is normally able to deliver something that's ordered.

Maybe I should have “planned ahead.” Maybe I “shouldn't blame others.”

Amazon was also hit by a problem of accidentally selling glasses that were potentially unsafe (or at least the source was not verified or properly certified). Perhaps that's a “buying mistake” on the part of somebody at Amazon. But who has really worried about eclipse glasses and all of the proper specs (pun intended) until now? Vanderbilt University had to recall 8,000 glasses as well (which creates a safety risk if some people don't get the word and try the glasses on Monday, thinking they are safe).

Maybe we didn't “source properly” or “pay attention to safety requirements.”

As it says in this article:

With an online retail giant out of the picture, supply is even more strained.

So, Amazon is out of stock. Retailers that were supposed to have them in my area, including Lowes, 7-Eleven, Publix, and Wal-Mart are all sold out. I've visited and called many stores and basically gave up. I'm going to hope to snag a pair at a local event Monday afternoon, or I'll just watch NASA TV.

If you are a manufacturer of eclipse glasses, how would you have forecasted demand? You'd have no historical sales data to go with. Would you forecast one for every person in the country? Perhaps.

When planning manufacturing and inventory in a supply chain, there are always two types of risk:

- The risk of excess inventory

- The risk of lost sales due to stock outs

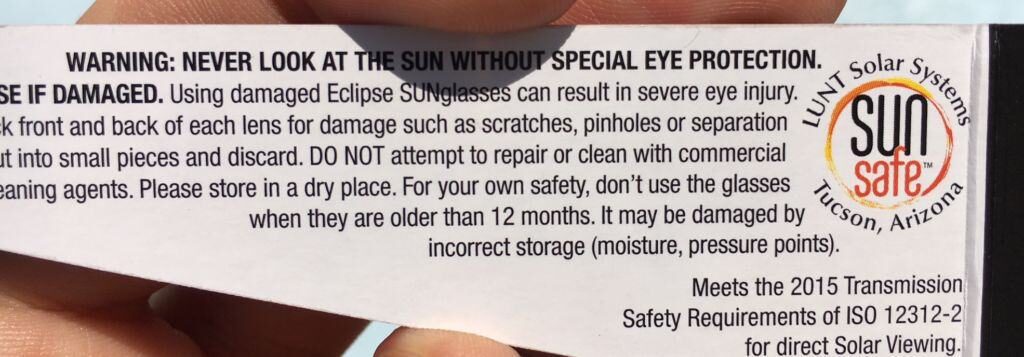

Retailers and manufacturers understandably wouldn't want to get stuck with a ton of unsold eclipse glasses. Then again, they are small, light, and inexpensive. Also, they probably have a long shelf life (if stored properly),— actually, see the warning on the glasses below — so any unsold glasses could be possibly shipped to another part of the world for the next major eclipse (if regulatory and ISO standards are the same worldwide). Or, they could be held in inventory until 2024 (no, maybe not). Yes, there is a cost to that… the cost of storage, moving them, counting them, etc. That's why companies don't like inventory… but lost sales are a problem too.

I think a regular man-on-the-street interview subject had the right idea when being quoted in this article:

Bill Hobday of Schaumburg has called several stores in search of a pair, but every place has been sold out. He's leery of buying them online and questions why retailers didn't have more in stock, given all the hype about the eclipse.

“They probably cost someone 10 cents to make, and the margin on these things has to be awesome,” he said with a laugh. “I'm going to keep looking … but I'll probably end up watching it on TV.”

This article discusses some of the details on the Florida coast:

“We sold out within about two weeks,” said Jon McMath, assistant manager at the Lowe's of the 700 glasses the store received. “We sold out probably last Thursday and we've been getting calls nonstop ever since.”

In a smoothly-functioning supply chain, running out of glasses quickly should have triggered an additional order. But, it's possible the manufacturers can't keep up and it's also possible that no retailer wants to get stuck with inventory that will essentially have zero value come Monday evening?

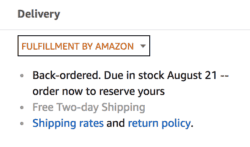

A few Amazon retailers are sold out, but anticipated getting more supply August 21 or 22, which is clearly too late to meet the market need. Oops — excess inventory.

Maybe part of the problem is that public interest is high and these eclipse glasses only sell for $1 or $2, so there isn't enough incentive for the supply chain to care? That seems like an economics and market failure. Shouldn't retailers have charged a higher price? There seems to be demand, but the supply chain isn't responding.

Maybe we should have “charged more” for these “special glasses.”

As USA Today explains, it sounds like one company is trying really hard to keep up with demand.

Demand for the special glasses — which allow you to safely view the event — is fast and furious. American Paper Optics in Bartlett, Tenn., the company that produces the most eclipse glasses, is working speedily to churn them out. So far, the company has produced about 37 million glasses and is shipping out as many as 500,000 each day. The company had hoped to make 100 million of the glasses.

They “had hoped to make 100 million.” It goes to show that hope is not a strategy, as they say. It seems like they are falling far short of that goal. I wonder why? They describe themselves as “your go to eclipse glasses” supplier. I wonder why others didn't anticipate and enter this market?

If they've made 37 million at a pace of up to 500,000 a day, that's about 74 days of production. Did they have equipment problems? Supplier problems upstream that constrained production? Did the retailers not forecast properly? It would be an interesting case study to dig deeper into what happened.

Maybe we should have “started ramping up earlier.”

The cost of producing inventory early and storing it probably would have been lower than the cost of buying more capital equipment. I would have “buffered” this demand spike with inventory instead of equipment, considering equipment might have little value after the spike in demand (unless you can also, perhaps, make 3D glasses, but those are falling out of style?).

It's tempting to say, “All inventory is bad” from a Lean perspective, but sometimes inventory has a strategic purpose. Lean manufacturers sometimes find it more cost effective to “level load production,” holding some inventory to buffer against variation in demand. As I learned years ago from a Japanese consultant, “low inventory” is not the primary goal… meeting customer demand is. Meet customer demand with the lowest-possible inventory.

Here is an article about the company, which has been making eclipse glasses since the 1990s, which says:

“This summer, American Paper Optics has received upwards of 13,000 orders of eclipse glasses daily, doing $2.7 million of business in a single day.”

The owner says:

“It's crazy. It's absolutely gone nuts,” says Jerit, whose business-like tone contains notes of a showman's enthusiasm. “We're going to sell 40 million plus glasses. My original goal was 100 million, but I didn't get the big corporate sponsors–Coke, Pepsi, Intel. Ecommerce and retail have been excellent, and I've been blown away by the website and by Amazon resellers.”

If they didn't get “big corporate sponsors,” it's a shame that they didn't figure out how to produce these to be sold at a price point that would have been profitable and ensured sales. Maybe they needed an infusion of cash from sponsors? I would have gladly paid more than $2, but I also don't want to be gouged online, especially if you can't then trust that the glasses are legit.

All of this also goes to show that a simple, inexpensive product can be easy to produce, but very difficult to provide throughout a supply chain, especially when there's a big spike in demand. Maybe this an extreme example of the “beer game effect” (aka the “bullwhip effect?“) The problem in “the beer game” is more easily identified than solved, although practical lessons involve better visibility and communication throughout a supply chain, as would shorter lead times.

One retailer in Canada said they missed the window for ordering more when they wanted to:

He said the chain ordered double the amount of glasses it thought it would need, but that still wasn't enough to meet demand. The glasses didn't sell at first, he added, and by the time sales picked up, it was too late to re-order from the manufacturer, one of the more popular companies listed by the American Astronomical Society as a reputable supplier.

The USA Today article also spells out safety tips. Without good public education, I wonder how many people are going to either damage their eyes by staring at a partial eclipse? What does that do to our emergency departments? Or demand for ophthalmologist visits? Are they anticipating this and trying to staff accordingly? How many people are going to damage their cameras or smart phones by trying to take photos of the eclipse? We'll see.

Maybe I shouldn't have “stared at the sun” without “proper protection.”

The eclipse is a reminder that we take a lot for granted in our modern-day, internet-enabled supply chains, where we expect to get any product, any time. Supply chains can be very hard to manage, as we often see in healthcare and the pharmaceutical supply chain, where we have shortages of routine products (like saline solution bags) or shortages when a rare spike in demand occurs (such as in the Ebola crisis a few years back).

Maybe if I had “cared more” about the eclipse, I might have tried “buying them sooner.”

Guilty as charged.

Of course, the Orlando sky is forecast to look like this Monday afternoon (as it did on Sunday afternoon when I took this photo):

No, I'm not driving six hours to South Carolina to the totality path. They could have clouds, too.

What are your plans for the day? Did you find eclipse glasses? Here's an article about what to do without eclipse glasses.

What do you think a “Lean manufacturer” would have done in this scenario? Would they have produced the right number of glasses, getting them to the right places, and the right times? Or would they have stayed out of a flukey market like this that doesn't have anything close to level-loaded demand?

You can also view and share a shorter version of this article that appears on LinkedIn.

After the Eclipse

As I mentioned in the comment below, I had a kind neighbor in my condo building who had an extra pair. Thanks for his kindness and sharing.

We only had about 85% coverage here in Orlando, but the sun was noticeably less intense on my skin standing out there. The biggest risk was probably of sunburn. The light was weird, kind of like looking through a tinted window during our peak coverage.

The glasses I had were ISO certified, which I hoped was a legit certification and not the mark of a counterfeit. I didn't stare at the sun for long periods… glances, just to be safe (which reminds me of a Seinfeld episode).

They were from a company in Arizona that was on the “approved and safe” vendor list (as long as these were legitimately from them):

From an inventory management standpoint, it's interesting that they warn not to use glasses older than 12 months because they could be damaged by incorrect storage. That's always a risk with inventory — risk of damage.

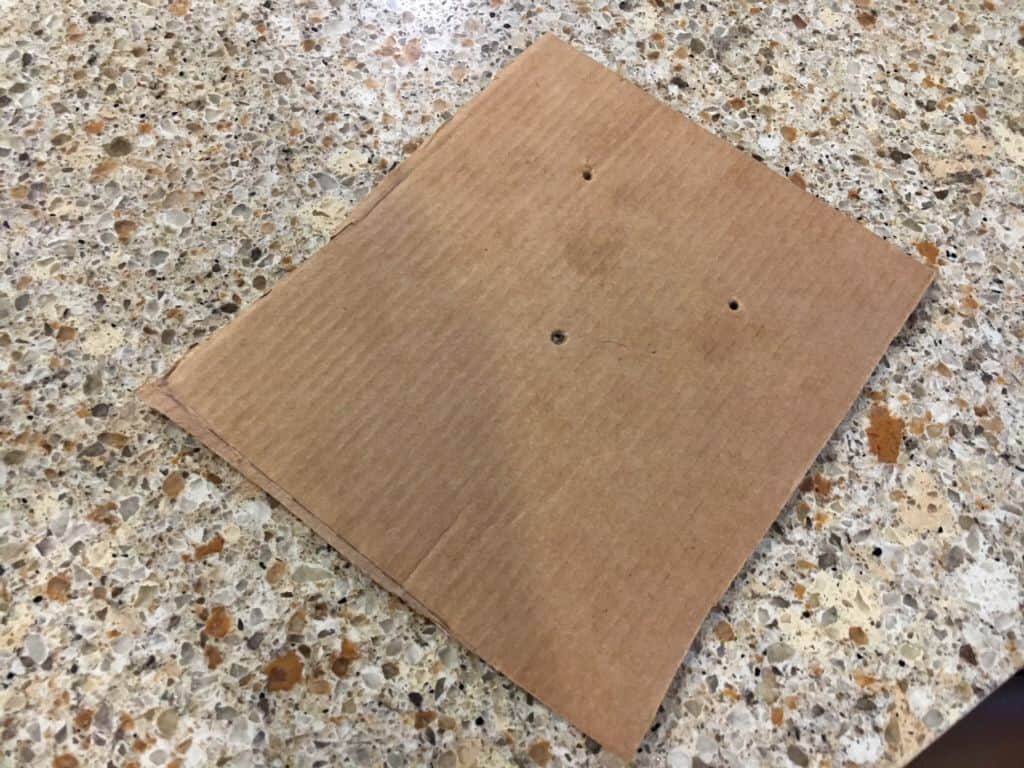

Here is the pinhole projector that I made, experimenting with different-sized holes:

And here's the projection — it worked pretty well!

And me being a nerd in the glasses:

What do you think? Please scroll down (or click) to post a comment. Or please share the post with your thoughts on LinkedIn – and follow me or connect with me there.

Did you like this post? Make sure you don't miss a post or podcast — Subscribe to get notified about posts via email daily or weekly.

Check out my latest book, The Mistakes That Make Us: Cultivating a Culture of Learning and Innovation:

Today I learned: 2 million glasses were given away by public libraries across the U.S. Some of them turned out to be recalled. The Orlando Public Library I visited this morning made an announcement at opening about not having glasses unless you registered for one of their events later.

I was fortunate…

I live in a condo building where, as it turns out, a neighbor had some extra glasses to share. A group of his co-workers came over and there were enough glasses to go around, so we watched from the roof.

In a day and age when many people are jerks, it’s always nice to appreciate people being kind and sharing

Here’s an article about injuries from Monday:

Foot fractures, eye damage and sprains: Doctors are already seeing patients with eclipse injuries